[Editor’s note: This essay is published here in conjunction with the publication of Film International 69, vol. 12, no. 3/2014, a special issue devoted to Contemporary Independent Iranian Cinema.]

The cinema of Jafar Panahi highlights two crucial strains of the problematic of Iranian independent cinema: the conditions of the production of art in Iran and the politics of the global circulation and reception of Iranian films. Since his alleged activism during 2009’s Green Wave and his subsequent imprisonment, Panahi has attained global recognition as a political figure in the realm of Iranian cinema. Although his much-celebrated film made under house arrest, This is Not a Film (In Film Nist, 2011), has been recognized, in part, for its equal attention to both medium-specific and socio-political concerns, his status within post-revolutionary Iranian cinema suggests that it is not easy to unravel why certain types of filmmaking are seen as political where others are not.

For example, Abbas Kiarostami’s work has often been interpreted as non- or apolitical, even when it has explicitly engaged the conditions of filmmaking and film viewing in Iran (cf. Denby 2011). And Panahi, himself, did not become known as a political filmmaker until 2000’s The Circle (Dayereh). Yet, Panahi’s first two films, The White Balloon (Badkonake Sefid, 1995) and The Mirror (Ayneh, 1996) show, if not an explicit confrontation of the political in the manner of This is Not a Film and Closed Curtain (Pardé, 2013), certainly a direct troubling of the parameters guiding the production and circulation of film in Iran. Indeed, The Mirror is often cited as exemplary of post-revolutionary Iranian cinema. Furthermore, Panahi’s explicitly political work seems to hold more value for some critics; this type of reading carries an implicit devaluation of his earlier, more meditative efforts such as The Mirror. For example, in the arts and culture magazine, Slant, Tina Hassania states “2011’s This Is Not a Film and this year’s Closed Curtain, co-directed by Kambuzia Partovi – easily surpass Panahi’s previous films in their aesthetic complexity, intellectual rigor, and, above all, reckless abandon” (Hassania: 2013).

I perceive these readings as more than just a devaluation of that which is allegedly “purely” aesthetic, but also as profoundly revelatory of the life of Iranian films once they enter the world market. I use the word market here to name both the economics and politics of international film festivals, but also the less tangible ways in which certain types of non-Western cinemas circulate as so-called humanist meditations, whereas others – such as This is Not a Film – are read as an artistic call to arms. Something happens to a film in the space between the moment it enters the global market and its later life as a part of a cinephilic and/or critical (mental) catalogue. This moment is one of reading: it comes with a plethora of assumptions and carries profound implications for the future of a film. It is, in part, a problem stemming from what Brian Price describes as “an advanced state of cultural isolationism” despite the fact that “access to films from around the world has never been easier or more comprehensive” (Price 2010: 114-115). I would add, not only are films more easily accessible, but also that accessibility itself is often a substitute for deeper engagement with a given culture. Furthermore, the shifting politics of desire tend to generate evaluations of films that encompass more than just the text itself. Without diminishing the importance of a film like This is Not a Film, it does not seem difficult to understand why global audiences cathect to it as deeply political and not to a film like The Mirror. Likewise with the prefix “new” in New Iranian Cinema, which may not represent any novelty other than a desire to see Iran differently after the multiple political crises of the 1970s and 80s.

I perceive these readings as more than just a devaluation of that which is allegedly “purely” aesthetic, but also as profoundly revelatory of the life of Iranian films once they enter the world market. I use the word market here to name both the economics and politics of international film festivals, but also the less tangible ways in which certain types of non-Western cinemas circulate as so-called humanist meditations, whereas others – such as This is Not a Film – are read as an artistic call to arms. Something happens to a film in the space between the moment it enters the global market and its later life as a part of a cinephilic and/or critical (mental) catalogue. This moment is one of reading: it comes with a plethora of assumptions and carries profound implications for the future of a film. It is, in part, a problem stemming from what Brian Price describes as “an advanced state of cultural isolationism” despite the fact that “access to films from around the world has never been easier or more comprehensive” (Price 2010: 114-115). I would add, not only are films more easily accessible, but also that accessibility itself is often a substitute for deeper engagement with a given culture. Furthermore, the shifting politics of desire tend to generate evaluations of films that encompass more than just the text itself. Without diminishing the importance of a film like This is Not a Film, it does not seem difficult to understand why global audiences cathect to it as deeply political and not to a film like The Mirror. Likewise with the prefix “new” in New Iranian Cinema, which may not represent any novelty other than a desire to see Iran differently after the multiple political crises of the 1970s and 80s.

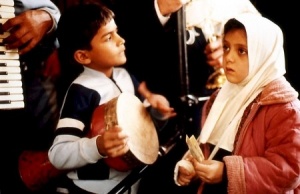

The Mirror is invariably described as containing a simple narrative built around the everyday life of a child and pivoting on the tension between reality and fiction. The subversion of the impression of reality is said to occur at the moment that Mina, the young protagonist of The Mirror, looks directly into the camera. She is suddenly addressed by a male offscreen voice saying, “Mina, don’t look into the camera.” In response, she rips off her school-issue hijab and says, “I don’t want to act anymore!”

So much has been made of this moment that it is necessary to ask why this kind of explicit reflexivity in Iranian cinema generates a disproportionate level of interest in relation to the film as a whole. Post-revolutionary cinema is, on the one hand, celebrated for continuing the legacy of neorealism. On the other hand, it is celebrated for blurring the lines between what is “reality” (a documented pro-filmic event?) and what is fiction (art or artifice?) through precisely this kind of moment: breaking the fourth wall. It takes careful parsing to determine when these types of interpretations occur and where they overlap, particularly if we are to examine the ways that interpretation implicitly limits cinema’s possibilities based on genre expectations and the geo-politics of film criticism. Interpretations of Iranian cinema as lying somewhere between “reality” and “fiction” in fact demonstrate a remarkably simplistic notion of “reality” – that it can be easily contained, grasped, and represented on film. This assumption flies in the face of much film theory – particularly work on documentary and ethnographic cinema – that has already questioned the possibility of the representation of reality.[1]

Although Iranian art cinema does often feature non-actors working without scripts, or employs individuals to reenact on film events that happened in their lives, as in the case of Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up (Nema-ye Nazdik, 1990), the term “reality” is nonetheless too readily used to describe these practices. Furthermore, the dichotomy of reality and fiction loses its explanatory power when it emerges from assumptions about the conditions of the production of art in Iran. Film scholar Hamid Naficy argues that although neorealism was a considerable influence on the pre-1979 New Wave and can continue to be described as a prominent concept in post-revolutionary Iranian cinema, many post-revolutionary films “embody certain deconstructive practices that counter or problematize realism or neorealism” (Naficy 2012: 235). Naficy’s description of some of Kiarostami’s post-revolutionary practices is a fitting description of much of Iranian art cinema after 1979:

“Kiarostami’s deconstructive and counterrealistic practices include self-referentiality, self-inscription, and self-reflexivity as well as ironic blending of reality and fiction, forms of distancing, indirection, and sly humor. By these means, the most well known practitioner of neorealism is also the best violator of what Kamran Shirdel aptly called ‘the dictatorship of neorealism’” (Naficy 2012: 235).

Given Iran’s relative isolation for the past three decades, it is thus curious that terms like “realism” were used – largely in the Western press – in enthusiastic descriptions of what was deemed the “New Iranian Cinema.” In “Perspectives on Recent (International Acclaim for) Iranian Cinema,” Azadeh Farahmand alludes to the influence of global politics for what she deems as disproportionate attention to the novelty of the “New Iranian Cinema” (Farahamand 2002: 101). It is no wonder that under these circumstances a filmmaker like Kiarostami would become a polarizing figure: acclaimed abroad for his film style as well as his engagement with realism, while reproached domestically for allegedly aiming to represent all of Iran with rural narratives like those of the Koker trilogy. Kiarostami’s recent work, most notably 2008’s Shirin, provides ample evidence that his work and thinking is experimental, non-linear, and deeply committed to a non-narrative cinema. Thus when the term realist is applied to Iranian cinema a priori, it is necessary to ask if the realist imperative is not an unfortunate demand placed on non-Western cinemas in the context of the Anglo-American academy.

Here, I examine how Iranian independent cinema thinks the dual problems of collectivity/community and the conditions of the production of art. To give specificity to these problems, I shall focus my analysis on The Mirror and its meditation on the limits and possibilities of bounded space. The film allows the unfulfilled promise of Iran’s New Wave (Mowj-e No) of the 1960s and 70s and the project of the Islamic Republic of Iran to weave through each other. By engaging both of these problems at once, The Mirror folds the question of realism into the historical dilemma of collectivity as a challenge for new formal strategies within what is called “independent cinema.” Moreover, it already asks the question of how to present what is “real” when the representational rules of the state do not seem to align with experienced reality; Panahi addresses this directly in This is Not a Film when he alludes to avoiding situations that are “impossible,” such as women wearing the hijab in private, diegetic spaces.

The narrative of The Mirror rarely diverts from its explicit goal: for the young Mina to make her way home from school without her mother to accompany her. The story begins with Mina waiting for her mother to pick her up from school at the usual time. She is outside her school and as time passes, she realizes that her mother may not show up. She takes matters into her own hands and decides to take the bus to a terminal where she imagines she will catch up with her mother, with whom she can carry out the final leg of the trip.

The Mirror is best characterized as two films. The first is this seemingly simple narrative of a girl, lost without her mother, looking to make her way home. This film looks at Tehran through Mina’s eyes. The second film contained within The Mirror is everything that occurs after the moment when the fourth wall is broken and Mina declares that she no longer wants to act. The second film looks for Mina as she careens through the Tehran traffic making her way home. By the time the second film takes place, the viewer is no longer certain whether Mina’s attempt to get home on her own is a “real” problem faced by the young actress or that the actress continues to play this role, aware that the film crew has followed her long after her stated desire to leave the production. The second film, as it were, analogizes the difficulties of making a film with the limitations of mobility in the metropolis.

The film’s opening shot is a 360-degree pan of the four corners of the intersection where Mina’s school is located. As the camera moves left, it is aided by the movement of a steady flow of young girls in white hijabs leaving the school and crossing the street. They take the camera through two crossings, after which it meets an elderly man struggling to cross the unending and inhospitable Tehran traffic. He must return to the sidewalk but the camera stays on its own course, catching up with two young workers with rugs hoisted on their backs. They walk out of the frame after they cross the street. As they leave, two women in chadors, each pushing a baby carriage, walk into the shot as they cross the street to the school. They each greet their school-aged children as the children greet their infant siblings. The camera cuts to a medium close-up of Mina who, while waiting for her mother, deliberates getting permission for attending a social activity with a friend. The friend offers, “Shall I ask my mother to call yours?”

The film’s opening shot is a 360-degree pan of the four corners of the intersection where Mina’s school is located. As the camera moves left, it is aided by the movement of a steady flow of young girls in white hijabs leaving the school and crossing the street. They take the camera through two crossings, after which it meets an elderly man struggling to cross the unending and inhospitable Tehran traffic. He must return to the sidewalk but the camera stays on its own course, catching up with two young workers with rugs hoisted on their backs. They walk out of the frame after they cross the street. As they leave, two women in chadors, each pushing a baby carriage, walk into the shot as they cross the street to the school. They each greet their school-aged children as the children greet their infant siblings. The camera cuts to a medium close-up of Mina who, while waiting for her mother, deliberates getting permission for attending a social activity with a friend. The friend offers, “Shall I ask my mother to call yours?”

With this opening shot, Panahi straightaway sets the stage for a meditation on a number of issues: the immediate space of the narrative, the boundaries of film production in post-revolutionary Iran, the circuitous movement of Mina and the film, and the suggestion of an impending break with the seemingly harmonious borders of this circle. The limits of the space are never limiting. In fact, they ensure a kind of security for a child as young as Mina in the bustle of a city like Tehran. From Revolution Square to Republic Square. This route repeats itself ad nauseaum, in what is perhaps the film’s most obvious touch of didacticism.

Panahi’s young female protagonist is a telling choice – a repetition of his young female protagonist in The White Balloon, released only two years prior to The Mirror. At this historical moment, he is one of the few filmmakers in Iran to focus on a female child. This fact alone has received curiously little attention given that much of the critical writing on Iranian post-revolutionary cinema emphasizes the absence of women (as a means of avoiding censorship regulations, although Panahi later directly confronts the situation of women in The Circle) as well as decrying the child as a depoliticized figure.[2]

The young girl in The Mirror is the figure through which the historical dilemma of collectivity and its relation to realism is connected. This is not the first time in the history of Iranian cinema that the body of a relative outsider has been used to critique and/or entirely circumvent the nationalist imperative. Think, for example, of the leper body in Forough Farrokhzad’s The House is Black (Khaneh Siah Ast, 1962) or the young woman in Marva Nabili’s brilliant The Sealed Soil (Khake Sar Beh Morh, 1977). Mina has the rough-and-tumble affect of a young school child: her backpack is nearly always falling off her shoulders and we wonder if the contents will be contained or if she will lose the bag, her coat is open and seems cumbersome, and her physical size set against the grandeur of the city gives the impression that she will fall or lose herself in the dross. And yet the heterogeneity of those she encounters insists on one point of equivalence: that Mina can rely on even the most dubious of characters. Even when the figures she encounters aren’t overly concerned with her well-being, like the traffic cop who, despite the young girl’s insistence, does not remember having met Mina or her father, they are similarly consumed by the task of metropolitan life. The obliviousness with which the ancillary characters deal with Mina erases the possibility of any threat that will come to her in the city.

Like The House is Black, Panahi’s film seems to insist that it is not the encounter with strangeness that is to be feared, but rather what our responses to that which is unknown prompts. Take for example the elderly woman on the first bus that Mina boards. She is overheard lamenting to a younger woman – whom she has just met – about how much she has suffered at the hands of her children. She speaks with a thick, regional accent that marks her as an ethnic minority. Her children are urban professionals who keep her away from her grandchild for fear he will “learn” her accent, and they refuse to introduce her to friends and neighbors. She roams the city on buses, with nowhere to go. In the “second” film she even admits to Mina that she finds herself sitting on benches in the city to kill time. She can only go home when the time is appropriate; when she will remain invisible. The discussion with the elderly woman gives particular poignancy to Mina’s own circling around the city. The absence of Mina’s mother is both the initial trauma of her journey and what permits it to continue. She too is stuck outside in the streets, albeit temporarily, suffering from a comparable form of “unrecognition.”

Like The House is Black, Panahi’s film seems to insist that it is not the encounter with strangeness that is to be feared, but rather what our responses to that which is unknown prompts. Take for example the elderly woman on the first bus that Mina boards. She is overheard lamenting to a younger woman – whom she has just met – about how much she has suffered at the hands of her children. She speaks with a thick, regional accent that marks her as an ethnic minority. Her children are urban professionals who keep her away from her grandchild for fear he will “learn” her accent, and they refuse to introduce her to friends and neighbors. She roams the city on buses, with nowhere to go. In the “second” film she even admits to Mina that she finds herself sitting on benches in the city to kill time. She can only go home when the time is appropriate; when she will remain invisible. The discussion with the elderly woman gives particular poignancy to Mina’s own circling around the city. The absence of Mina’s mother is both the initial trauma of her journey and what permits it to continue. She too is stuck outside in the streets, albeit temporarily, suffering from a comparable form of “unrecognition.”

Panahi effectively demonstrates the difficulty of mobility and resolution, due not only to Mina’s age but also her size. In both sections of The Mirror we see her grapple with invisibility due to her height, disappearing behind the buses careening down the avenues. Likewise, in each of the two films, she attempts to use a public payphone to call home. Her first struggle is to become visible in the queue for the phone, the second to have her business taken seriously by the adults waiting to use the phone. One woman addresses her as child (bacheh) and instructs her to be quick. However, Mina must stand on her book bag in order to be able to deposit change into the coin slot. The cast on her arm, which is prominently displayed early in the film, quickly reveals itself as artifice when she ignores the sling and uses her arm to hoist herself up against the sides of the phone booth. Both here and on the busses she rides, Mina manages to compensate for her invisibility. The strength of this ability is only heightened when, in the second half of film, she manages to physically avoid the space of the frame to the chagrin of the film-crew-within-the-film.

Panahi effectively demonstrates the difficulty of mobility and resolution, due not only to Mina’s age but also her size. In both sections of The Mirror we see her grapple with invisibility due to her height, disappearing behind the buses careening down the avenues. Likewise, in each of the two films, she attempts to use a public payphone to call home. Her first struggle is to become visible in the queue for the phone, the second to have her business taken seriously by the adults waiting to use the phone. One woman addresses her as child (bacheh) and instructs her to be quick. However, Mina must stand on her book bag in order to be able to deposit change into the coin slot. The cast on her arm, which is prominently displayed early in the film, quickly reveals itself as artifice when she ignores the sling and uses her arm to hoist herself up against the sides of the phone booth. Both here and on the busses she rides, Mina manages to compensate for her invisibility. The strength of this ability is only heightened when, in the second half of film, she manages to physically avoid the space of the frame to the chagrin of the film-crew-within-the-film.

One of my broader aims here is to open a debate on the myriad ways in which Iranian cinema has historically dealt with the problem of community and collectivity. I take the position that these imaginings have not in every case reinforced the nationalist vision of the state, but rather dared to imagine a mode of collectivity – being together – that has not yet been achieved. At the level of form, the intrusion of “artifice” into the dogma of realism – in this context known as “reality-fiction” – is what allows this not-yet to occur. Thus what is often called self-referentiality, or an obsession with fact/fiction in Iranian cinema, can be considered a new form that takes (neo)realism up afresh in a new political and historical context. The narrative of The Mirror is not about social strife per se. On the contrary, both the narrative of Mina trying to get home and the second narrative of trying to find her and keep the production running use the literal and metaphorical figure of the circle as a container for thinking about collectivity. The circumscribed space of the film is also a meditation on the conditions of filmmaking and, curiously, also its condition of possibility. I read the circular trials of The Mirror’s film crew as not wholly convinced by what some have called the possibilities of film language under the (then) new guidelines of the Islamic Republic of Iran. For example, in Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema, Negar Mottahedeh makes a compelling case for the ways in which the post-revolutionary film language is generative of new codes, structures, and syntax (2008). The Mirror represents a contemporaneous attempt to think cautiously about these structures.

One of my broader aims here is to open a debate on the myriad ways in which Iranian cinema has historically dealt with the problem of community and collectivity. I take the position that these imaginings have not in every case reinforced the nationalist vision of the state, but rather dared to imagine a mode of collectivity – being together – that has not yet been achieved. At the level of form, the intrusion of “artifice” into the dogma of realism – in this context known as “reality-fiction” – is what allows this not-yet to occur. Thus what is often called self-referentiality, or an obsession with fact/fiction in Iranian cinema, can be considered a new form that takes (neo)realism up afresh in a new political and historical context. The narrative of The Mirror is not about social strife per se. On the contrary, both the narrative of Mina trying to get home and the second narrative of trying to find her and keep the production running use the literal and metaphorical figure of the circle as a container for thinking about collectivity. The circumscribed space of the film is also a meditation on the conditions of filmmaking and, curiously, also its condition of possibility. I read the circular trials of The Mirror’s film crew as not wholly convinced by what some have called the possibilities of film language under the (then) new guidelines of the Islamic Republic of Iran. For example, in Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema, Negar Mottahedeh makes a compelling case for the ways in which the post-revolutionary film language is generative of new codes, structures, and syntax (2008). The Mirror represents a contemporaneous attempt to think cautiously about these structures.

In Cinema 2: The Time-Image, Gilles Deleuze argues that whereas in “classical” cinema what he calls “the people” pre-existed prior to their representation in film, that is no longer the case in modern, political cinema (Deleuze 1989: 216). He writes, “this acknowledgement of a people who are missing is not a renunciation of political cinema but on the contrary the new basis on which it is founded” (Deleuze 1989: 217). Thus when he proclaims that “the people are missing,” Deleuze refers to a situation – for him it is to be found in the postcolonial cinemas of Glauber Rocha and Ousmane Sembène, to name two examples – that presents a new opportunity for thinking collectivity. For example, Sembène’s film Xala grapples with this precise problem: once decolonization has occurred, how does a nation forge community on the basis of something new, in addition to a community based on anti-colonial action.

I would argue that several pre-revolutionary Iranian New Wave films share a common concern with constructing new collectivities, though under different circumstances, such as imagining non-nationalist modes of opposition to monarchical rule. The Mirror finds itself in a similar position, both in terms of new ways to think about collectivity, as well as new ideas and problems in cinema. The film begins with a public that is as bound as the circle within which the film circulates. Thus the project of the film is to show how cinema, as a political project, and the formation of a new collectivity, enunciate through and with one another. The second film within The Mirror offers one extraordinary example of such a recuperation. Mina is lost to the film crew save for her microphone. The crew follows her at a distance as she tries to make her way home. She is only sometimes in view of the camera, but audibly, her every step can be traced. At one point, we hear her encountering an elderly man with an uncanny voice: he was the actor who played John Wayne in Persian-dubbed versions of his films. On one hand, we can read this exchange as a nod to Iranian cinema’s past – to the break in production that occurred after the 1979 revolution. The actor can no longer earn his living this way precisely because of a political project whose outcomes could not have been foreseen. Yet his voice, existing in all its artifice, is a salve that changes the tenor of the moment and reinforces the notion that we do not need to see something in order to believe it or to make it happen: neither the actor, Mina, or the collectivity that is articulating itself amidst a new political project. Panahi reminds the viewer that “this is not a portrait” of the city but a reflection on all that it carries with it into its future.

I would argue that several pre-revolutionary Iranian New Wave films share a common concern with constructing new collectivities, though under different circumstances, such as imagining non-nationalist modes of opposition to monarchical rule. The Mirror finds itself in a similar position, both in terms of new ways to think about collectivity, as well as new ideas and problems in cinema. The film begins with a public that is as bound as the circle within which the film circulates. Thus the project of the film is to show how cinema, as a political project, and the formation of a new collectivity, enunciate through and with one another. The second film within The Mirror offers one extraordinary example of such a recuperation. Mina is lost to the film crew save for her microphone. The crew follows her at a distance as she tries to make her way home. She is only sometimes in view of the camera, but audibly, her every step can be traced. At one point, we hear her encountering an elderly man with an uncanny voice: he was the actor who played John Wayne in Persian-dubbed versions of his films. On one hand, we can read this exchange as a nod to Iranian cinema’s past – to the break in production that occurred after the 1979 revolution. The actor can no longer earn his living this way precisely because of a political project whose outcomes could not have been foreseen. Yet his voice, existing in all its artifice, is a salve that changes the tenor of the moment and reinforces the notion that we do not need to see something in order to believe it or to make it happen: neither the actor, Mina, or the collectivity that is articulating itself amidst a new political project. Panahi reminds the viewer that “this is not a portrait” of the city but a reflection on all that it carries with it into its future.

Seen through the problem of collectivity and the accompanying question of the conditions of filmmaking, The Mirror provides fertile ground for an analysis of what constitutes political film in the context of contemporary Iranian independent cinema. In This is Not a Film, Panahi exhibits a palpable frustration over the limits that have been set on his creativity. The phrase “this is not a film” is voiced in the film as a lament and not as the imperative command that the title might lead a viewer to expect. The film crew in The Mirror faces a similar dilemma of non-cooperation when the young Mina says, “I’m not acting anymore!” Rather than accepting her denial, the film reroutes itself into wholly unfamiliar territory wherein the aural takes primacy over vision. The actress is missing but the film continues by placing itself in a relation of equivalence with her dilemma. The film that continues despite its new restrictions forces the task of art to follow the circuitous path of the young girl, adrift in the city without the support of her mother. Mina’s makeshift alliances shape the contours of the city differently, opening up its future to the possibility of difference.

Seen through the problem of collectivity and the accompanying question of the conditions of filmmaking, The Mirror provides fertile ground for an analysis of what constitutes political film in the context of contemporary Iranian independent cinema. In This is Not a Film, Panahi exhibits a palpable frustration over the limits that have been set on his creativity. The phrase “this is not a film” is voiced in the film as a lament and not as the imperative command that the title might lead a viewer to expect. The film crew in The Mirror faces a similar dilemma of non-cooperation when the young Mina says, “I’m not acting anymore!” Rather than accepting her denial, the film reroutes itself into wholly unfamiliar territory wherein the aural takes primacy over vision. The actress is missing but the film continues by placing itself in a relation of equivalence with her dilemma. The film that continues despite its new restrictions forces the task of art to follow the circuitous path of the young girl, adrift in the city without the support of her mother. Mina’s makeshift alliances shape the contours of the city differently, opening up its future to the possibility of difference.

How does this difference occur? We see a poignant manifestation of its possibility in the final moments of the film. The film crew has finally caught up with Mina – visually – and she has arrived home. While waiting for her, the crew has been talking to the owner of a candy and toy shop. It turns out that he introduced the crew to Mina. A female member of the crew runs to Mina’s front door, seemingly imploring her to cooperate – to come back so the film can start shooting again. When she refuses, the door is shut on the film crew and on the spectator. But not before we hear the shop owner murmur, “I can introduce you to another little girl.” While The Mirror has been described as not overtly political, I argue that an examination of the film’s structure and its meditation on space provides strong evidence of its decidedly political project. Panahi wraps any number of subjects: mobility, the question of sexual difference, visibility, strangeness, generational differences, modernity – into a tightly executed narrative space within which the possibilities and conditions of making art erupt at every turn. The Mirror forces us to ask why, when faced with the task of criticism and scholarship, we continue to vehemently cling to binary thinking on the political and the aesthetic. The film follows the vibrant tradition of the pre-1979 New Wave by daring to relinquish some of the unifying structures that are known and comfortable in order to welcome the unknown that waits in the future.

Sara Saljoughi is a PhD candidate in the department of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota. She is completing a dissertation titled, “Burning Visions: The Iranian New Wave and the Politics of the Image, 1962-1979.” She has published essays and reviews in Iranian Studies, Jadaliyya, Film Criticism, and Discourse, among others.

References

Deleuze, Gilles (1989), Cinema 2: The Time-Image, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Denby, David (2011), “End Games: The Films of the Iranian Director Abbas Kiarostami,” New Yorker 87.4 (14 March, 2011), p. 65.

Farahmand, Azadeh (2002), “Perspective on Recent (International Acclaim for) Iranian Cinema,” Richard Tapper (ed.), The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 86-108.

Hassania, Tina (2013), “Toronto International Film Festival 2013: Closed Curtain Review”, Slant, 7 September. Accessed 22 October 2014.

Mottahedeh, Negar (2008), Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema. Durham: Duke University Press.

Naficy, Hamid (2012), “Neorealism Iranian Style” in Saverio Giovacchini and Robert Sklar (eds.), Global Neorealism: The Transnational History of a Film Style, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, pp. 226-239.

Sadr, Hamid Reza (2002), “Children in Contemporary Iranian Cinema: When We Were Children,” in Richard Tapper (ed.), The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 227-237.

Nichols, Bill (1991), Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Price, Brian (2010), “Art/Cinema and Cosmopolitanism Today” in Rosalind Galt and Karl Schoonover (eds.), Global Art Cinema: New Theories and Histories, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 109-124.

[1] One example in the context of documentary theory is Bill Nichols (1991).

[2] For an account of how the figure of the child has been taken up, see Sadr (2002).