By Brenda Benthien.

Cinefest, Hamburg’s international festival of German film history, focused this year on New Directions in Documentary Film. A range of volatile films from the 1960s through the 1980s illustrated how social upheaval and new technologies began to empower documentary filmmakers working to counter mainstream media.

Since 1988, venerable German film history book publisher CineGraph has run a film history conference in cooperation with the German Federal Film Archive. In 2004, its organisers took the next logical step and initiated a film festival in tandem with the conference. Each year’s programme focuses on a theme, its films curated by prolific CineGraph editor Hans-Michael Bock and culled from international archives (2013’s theme, European Censorship, was a bit sexier than this year’s). Lectures, discussions and prominent guests are introduced and placed within a cultural-historical framework, whose repercussions for contemporary media culture are parsed by scholars and the general public. Among CineGraph’s international partners are the Museum of Modern Art and the British Film Institute. Following the Hamburg event, portions of the film programme will travel to Berlin, Prague, Wiesbaden, Zurich, and other cities.

Cinefest draws historians from Europe and North America, and presents awards to film scholars: the Reinhold Schünzel prize for long-term service to the cultivation, conservation and dissemination of German film history, and the Willy Haas prizes, one for an important publication and one for a DVD edition on German-language film or film in Germany. In 2014, the Schünzel went to Dr. Horst Claus of the University of the West of England in Bristol. The Haas book award went to Walter Ruttmann and the Cinema of Multiplicity by Michael J. Cowan. Winner of the Willy Haas DVD award was Studio H&S: Walter Heynowski und Gerhard Scheumann: Filme 1964-1989, published by Ralf Schenk.

By way of introduction to some of the issues confronting documentary filmmakers, Cinefest organisers screened Ein Film für Bossak und Leacock (1984). Klaus Wildenhahn’s homage to Richard Leacock, a British-American pioneer of Direct Cinema, and Jerzy Bossak, a key figure in the development of the Polish post-war film industry, engages the directors in a dialogue about the very nature of documentary film. Leacock was a protégé of Robert Flaherty, whom he describes as hampered by primitive technology, especially pre-synchronized sound and static camera tripods. Leacock’s search for high quality, mobile, synchronous equipment to facilitate observation was ongoing until, in 1958, he hit upon the idea of installing a sort of Accutron watch mechanism inside a camera, allowing footage and sound to be synchronised. The revolutionary result of his invention is evident in Primary (1960), filmed during the U.S. presidential election. For the first time, an audience witnessed the sort of observational, hand-held style which most people today associate with documentary film.

One question raised in Leacock and Bossert in Wildenhahn’s film still resonates: to which extent is it acceptable for a non-fiction filmmaker to stage a film, and to what extent ought he to record “reality”? As we consider the current crop of homogeneous TV documentaries and purported reality shows, it’s worth remembering two things: filmmaking styles were once as varied and freewheeling as the era in which they were made, and the best documentarians, then as now, have sought to actually explore topics, not just ‘enact’ them. Indeed, a number of documentarians in the Cinefest series claim to have no interest in the limitations set by fiction films, with their preconceived endings. They’re more interested in waiting to see how things will turn out.

New social movements beginning in the 1960s were united in their fight against the bourgeoisie and grounded in their opposition to the manipulation of their stories by dominant media structures. More important to them than old-fashioned film craftsmanship – which afforded clean lighting and studio-perfect sound – was the message to be imparted. Opening the Cinefest conference were two early and decidedly messy protest films by West German filmmakers who would later make names for themselves. The late Harun Farocki’s 1968 student film, Their Newspapers, takes a youthful stab at the yellow press’s biased reporting on events shaking West Berlin and Vietnam. Claudia von Alemann was present to introduce This Is Only the Beginning – The Fight Will Continue, shot in in collaboration with a newly-formed film collective in Paris in the midst of the May 1968 revolution. In it, Jean-Luc Godard, Daniel Cohn-Bendit and other student activists discuss film’s importance as a weapon in the struggle against authority, and (presciently) its potential to become a direct mouthpiece of the people.

Carrying on the revolutionary theme, Starbuck Holger Meins (2001) tells the story of the German cinematography student who went on to join the anarchic Red Army Faction in the early 1970s, became a notorious radical, and died on hunger strike in prison in 1974, aged 33. A deliberate counterpoint to the prevailing narrative attached to the RAF by mainstream media including the reviled Axel Springer press, the film was made by Meins’s filmmaker friend Gerd Conradt and portrays the troubled activist as an intellectual, artist, husband and son.

In keeping with Cinefest’s commitment to internationalism, documentaries by Dušan Hanák and Chris Marker were two of many on view. Hanák came to Hamburg to discuss Pictures of the Old World (Czechoslovakia 1972), in which he queries the dispossessed elderly inhabitants of a remote village about the meaning of life, only to have the film banned by authorities. Chris Marker’s classic Sans Soleil (France 1982), a hypnotic pastiche of thoughts and images on our perception of histories, was assembled while he was a member of a political commune.

Julian Petley, Professor of Screen Media at Brunel University London, presented a Cinefest conference paper on the documentary and industrial conflict in 1970s and 1980s Britain. He described independent filmmaking organisations such as Cinema Action and the Film and Video Workshops, set up to contrast “official” documentaries produced by the BBC and ITV, as playing a key role in helping striking workers to defend themselves. Public broadcasters’ ‘impartiality’ requirements generally resulted in their support of the status quo as well as the demonisation of those who opposed it. Petley also curated a well-attended Cinefest programme consisting of several films which illustrate his points: Upper Clyde Shipbuilders (Cinema Action 1971), Not Just Tea & Sandwiches and The Lie Machine from The Miners’ Campaign Tapes (1984), and Ken Loach’s Which Side are You On? (1984) Petley noted that Loach initially pitched this project to ITV as a cultural film as he planned to incorporate striking miners’ poems and songs. Broadcast representatives banned the finished film however, on the grounds that it overstepped official guidelines on political impartiality. Indeed, Loach made the film partly to counter what he saw as the anti-union position of the mainstream media. Which Side are You On? was only broadcast by Channel 4 after Loach had won a prize at the Berlin Film Festival.

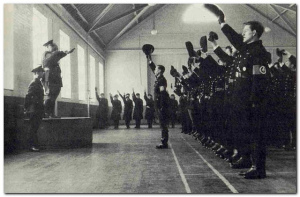

British film historian Kevin Brownlow was in Hamburg to present his 1964 It Happened Here on the occasion of the film’s 50th anniversary. Set in a fictional Britain in 1945, the film takes an alternative “what if?” approach to history by portraying the nation under permanent occupation by a victorious Nazi regime. Brownlow was a bit nervous about how the film would sit with a German audience, adding half-jokingly that he’d keep an eye out for the nearest exit. The story follows a principled English nurse who is forced by circumstances to join the Party and witnesses the terrible things her countrymen are capable of when given the authority. Though Brownlow is more successful recreating big historic pieces such as battle scenes and fascist marches than directing the bland actors, it’s astonishing that he made the film (with co-director Andrew Mollo) at the tender age of 20. Incidentally, he made no use of the emergency exit, as the audience’s reaction was politely unenthusiastic.

Though current works lie outside the scope of this festival, one Cinefest conference presenter fast-forwarded from the engaged films of the 20th century to today’s independent video and net activism. Berlin student Malte Voss drew the audience’s attention to the changed relationship between oppositional filmmakers and the media, quoting absurdist tactician Jello Biafra: “Don’t hate the media, become the media.” The splintering of official media outlets and the proliferation of high-quality mobile phone cameras has turned millions of people into potential documentarian-activists. Recent movements and protests were born out of the explosion of citizen media and activism. Ultra-fast technology has led to the simultaneity of event and broadcast: word of brewing protests travels instantly, and authorities now find it difficult to hide suppressive tactics due to the ubiquitous presence of cameras. Public discourse in and on the media is so open that a tipping point has been reached, as activists begin to clamour for more privacy and copyright protection. Voices of opposition still subvert state-sponsored media like they did in 1968, though they now record events in real time. Yet with so much ‘information’ on the Web, it is as difficult as it ever was to distinguish fact from fiction.

Brenda Benthien is a Hamburg-based freelance culture writer and translator. She works for both the Cleveland International Film Festival and the Nordic Film Days in Lübeck. Brenda previously wrote about film from Los Angeles, Munich, and Tokyo. You can find her website here.