We live in the age of the visible invisible; everything is supposedly available to us online, but in fact, only a small fraction of the knowledge and culture of even the most recent past is available on the web. The digitization of our culture is now an accomplished fact; physical media is disappearing, books are being harvested from library shelves and thrown into the anonymity of high density storage, digital facsimiles of these documents are often illegible or hidden behind pay walls. It’s a world of never-ending passwords, permissions, and a whole new group of “gatekeepers,” which the digital revolution was supposed to do away with, in which everyone got a place at the table. In fact, it has created a far more intrusive and much less intuitive group of cultural taste makers in place of the 20th century regime of editors, writers, critics and the like; technology specialists, who, really don’t understand the humanities at all, and are, in fact alarmed by the amorphousness of humanist work – after all, you know, it’s just so unquantifiable.

As Wieseltier notes, in part, in the January 7th issue of the NYT Sunday Book Review, “aside from issues of life and death, there is no more urgent task for American intellectuals and writers than to think critically about the salience, even the tyranny, of technology in individual and collective life. All revolutions exaggerate, and the digital revolution is no different. We are still in the middle of the great transformation, but it is not too early to begin to expose the exaggerations, and to sort out the continuities from the discontinuities. The burden of proof falls on the revolutionaries, and their success in the marketplace is not sufficient proof. Presumptions of obsolescence, which are often nothing more than the marketing techniques of corporate behemoths, need to be scrupulously examined. By now we are familiar enough with the magnitude of the changes in all the spheres of our existence to move beyond the futuristic rhapsodies that characterize much of the literature on the subject. We can no longer roll over and celebrate and shop. Every phone in every pocket contains a ‘picture of ourselves,’ and we must ascertain what that picture is and whether we should wish to resist it. Here is a humanist proposition for the age of Google: The processing of information is not the highest aim to which the human spirit can aspire, and neither is competitiveness in a global economy. The character of our society cannot be determined by engineers.”

Needless to say, Wieseltier’s essay has touched a real nerve among both humanists and the digerati – you can read some responses here – some agreeing with him, and some not, but for me, it seems that more often than not, he hits the mark straight on. As one reader, Carl Witonksy, wrote in response, “Leon Wieseltier’s essay should be required reading and discussion by all college students, regardless of major. Technology is penetrating every aspect of their lives, and they should come to grips with its pluses and minuses,” while Cynthia M. Pyle, co-chair of the Columbia University Seminar in the Renaissance, added that “for the humanities, the library is the laboratory, and books and documents are the petri dishes containing the ideas and records of events under study. We use the Internet, to be sure, and are grateful for it. But its rapid and careless ascent has meant that we cannot rely on it for confirmation of reality or of fact.”

Pyle goes on to note that “we require direct observation of material (stone, wood, ink, paper and parchment) documents, manuscripts and printed books, which we then subject to critical, historical analysis. We also require that these materials be spread out in front of us to analyze and compare with one another, like the scientific specimens they are. In great research libraries (which used to be the hearts of great universities), these were formerly available on site, so that an idea could be confirmed or contradicted on the spot. Instead, today librarians are taught that a delay of several days while a book is fetched from a warehouse dozens, or even hundreds, of miles away – to the detriment of the book – is irrelevant to our work. This is false. Our work is impeded by these assumptions, based on technological dreams, not on reality.”

I’ve seen the impact of this in many fields of the arts, which are now faced with a crisis unlike anything since the Middle Ages – the cultural work of the past is being relegated to archives, museums, and warehouses, and despite claims to the contrary, is not available in any meaningful way to the general public or students. Great swaths of material have been left unscanned and unindexed, and with the demise of paper copies becomes essentially unobtainable. Browsing through library stacks is not only a pleasurable experience; it is also an essential part of the discovery process and intellectual investigation. You come in, presumably, looking for one book, but now you find another. And another. And another. They’re all together in one section on the shelves. You’re not calling for a specific text, which would give you only one side of any given question – you have immediate access to them all, and can pick and choose from a wide variety of different perspectives. Now, it seems that only the eternal present is with us.

I wrote an essay that touched on some of these issues a few years ago for The College Hill Review about working in New York in the 1960s as part of the community of experimental filmmakers, aptly entitled “On The Value of ‘Worthless’ Endeavor,” in which I noted – again, in part – that,

“the only art today is making money, it seems; in fact, today, there are plaques all over New York identifying where this artist, or that artist, used to have a studio; today, all the locations are now office buildings or banks […] it seems that no one has time or money for artistic work, when, in fact, such work would redeem us as a society, as it did in the 1930s when Franklin Roosevelt put artists to work, and then sold that work, to get that segment of the economy moving again. Now, the social conservativism that pervades the nation today belatedly recognizes the power of ‘outlaw’ art, and no longer wishes to support it, as it might well prove – in the long run – dangerous.

Money can create, but it can also destroy. Out of economic privation, and the desperate need to create, the artists [of the 1960s] created works of lasting resonance and beauty with almost no resources at their disposal, other than the good will and assistance of their colleagues; a band of artistic outlaws. These artists broke the mold of stylistic representation […] and offered something new, brutal, and unvarnished, which confronted audiences with a new kind of beauty, the beauty of the outsider, gesturing towards that which holds real worth in any society that prizes artistic endeavor. It’s only the work that comes from the margins that has any real, lasting value; institutional art, created for a price, or on commission, documents only the powerful and influential, but doesn’t point in a new direction. It’s the work that operates off the grid, without hype or self-promotion, under the most extreme conditions, that has the greatest lasting value, precisely because it was made under such difficult circumstances.”

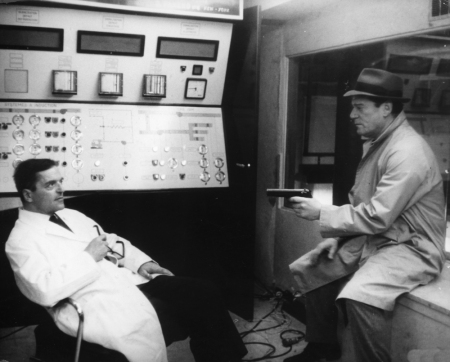

In his brilliant film Alphaville, Jean-Luc Godard depicted a futuristic dystopia – in 1965! – in which an entire civilization is run by a giant computer, Alpha 60, which directs and supervises the activities of all its inhabitants; a computer that is absolutely incapable of understanding nuance, emotion, or the chance operations of something like, for instance, Surrealism or poetry. As the supervisor of the computer and all its operations, one Professor Von Braun (played by Howard Vernon; the symbolism is obvious) is pitted against the humanist Secret Agent Lemmy Caution (the always excellent Eddie Constantine), who has been sent from the “Outerlands” to destroy the computer and restore humanity to Alphaville. As Von Braun warns Lemmy, “men of your type will soon become extinct. You’ll become something worse than dead. You’ll become a legend.” And as if to confirm this, Alpha 60 instructs his subjects that “no one has ever lived in the past. No one will ever live in the future. The present is the form of all life.”

In his brilliant film Alphaville, Jean-Luc Godard depicted a futuristic dystopia – in 1965! – in which an entire civilization is run by a giant computer, Alpha 60, which directs and supervises the activities of all its inhabitants; a computer that is absolutely incapable of understanding nuance, emotion, or the chance operations of something like, for instance, Surrealism or poetry. As the supervisor of the computer and all its operations, one Professor Von Braun (played by Howard Vernon; the symbolism is obvious) is pitted against the humanist Secret Agent Lemmy Caution (the always excellent Eddie Constantine), who has been sent from the “Outerlands” to destroy the computer and restore humanity to Alphaville. As Von Braun warns Lemmy, “men of your type will soon become extinct. You’ll become something worse than dead. You’ll become a legend.” And as if to confirm this, Alpha 60 instructs his subjects that “no one has ever lived in the past. No one will ever live in the future. The present is the form of all life.”

But, of course, it isn’t, and while the end of Alphaville strikes a positive note – technology reined in by Lemmy’s timely intervention, I can’t be so sure that this time, in real life, that there will be a happy ending. When a society no longer has bookstores, or record stores, or theaters because – supposedly – everything is online and streaming – when corporations make decisions, guided by the bottom line alone, as to what materials are disseminated and which remain in oblivion – and when mass culture alone – the popularity index – determines what works are allowed to find any audience, we’re in trouble. If you don’t know something is there, then you can’t search for it. Works buried in an avalanche of digital materials – and please remember that I am someone who contributes to this, and publishes now almost exclusively in the digital world – lose their currency and importance, just as libraries continue to discard books that later wind up on Amazon for one cent, in hardcover editions, where those of us who care about such work snap it up – until it’s gone forever.

But, of course, it isn’t, and while the end of Alphaville strikes a positive note – technology reined in by Lemmy’s timely intervention, I can’t be so sure that this time, in real life, that there will be a happy ending. When a society no longer has bookstores, or record stores, or theaters because – supposedly – everything is online and streaming – when corporations make decisions, guided by the bottom line alone, as to what materials are disseminated and which remain in oblivion – and when mass culture alone – the popularity index – determines what works are allowed to find any audience, we’re in trouble. If you don’t know something is there, then you can’t search for it. Works buried in an avalanche of digital materials – and please remember that I am someone who contributes to this, and publishes now almost exclusively in the digital world – lose their currency and importance, just as libraries continue to discard books that later wind up on Amazon for one cent, in hardcover editions, where those of us who care about such work snap it up – until it’s gone forever.

What will the future hold for those of us in the humanities? It’s a really serious question – perhaps the most important question facing us as scholars right now. Alpha 60 rightly recognized Lemmy Caution as a threat, and had him brought in for questioning, telling Lemmy that “I shall calculate so that failure is impossible,” to which Lemmy replied “I shall fight so that failure is possible.” The work of technology is valuable and useful, and without it, we would be stuck entirely in the world of physical media, which would mark an unwelcome return to the past. But in the headlong rush to digital technology, we shouldn’t sacrifice the sloppiness, the uncertainty, the messiness that comes from the humanities in all their uncertain glory, representing widely divergent points of view, with the aid of ready access to the works of the past, which, after all, inform and help to create the present, as well as what is to come. As Lemmy Caution tells Alpha 60, “the past represents its future. It advances in a straight line, yet it ends by coming full circle.”

What will the future hold for those of us in the humanities? It’s a really serious question – perhaps the most important question facing us as scholars right now. Alpha 60 rightly recognized Lemmy Caution as a threat, and had him brought in for questioning, telling Lemmy that “I shall calculate so that failure is impossible,” to which Lemmy replied “I shall fight so that failure is possible.” The work of technology is valuable and useful, and without it, we would be stuck entirely in the world of physical media, which would mark an unwelcome return to the past. But in the headlong rush to digital technology, we shouldn’t sacrifice the sloppiness, the uncertainty, the messiness that comes from the humanities in all their uncertain glory, representing widely divergent points of view, with the aid of ready access to the works of the past, which, after all, inform and help to create the present, as well as what is to come. As Lemmy Caution tells Alpha 60, “the past represents its future. It advances in a straight line, yet it ends by coming full circle.”

Wheeler Winston Dixon is the James Ryan Professor of Film Studies, Coordinator of the Film Studies Program, Professor of English at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and, with Gwendolyn Audrey Foster, editor of the book series New Perspectives on World Cinema for Anthem Press, London. His newest books are Cinema at the Margins (2013), Streaming: Movies, Media and Instant Access (2013); Death of the Moguls: The End of Classical Hollywood (2012); 21st Century Hollywood: Movies in the Era of Transformation (2011, co-authored with Gwendolyn Audrey Foster); A History of Horror (2010), and Film Noir and the Cinema of Paranoia (2009). Dixon’s book A Short History of Film (2008, co-authored with Gwendolyn Audrey Foster) was reprinted six times through 2012. A second, revised edition was published in 2013; the book is a required text in universities throughout the world. His newest book, Black & White: A Brief History of Monochrome Cinema, is forthcoming from Rutgers University Press Fall, 2015.