by John Duncan Talbird.

Back in college, my friends and I went to see Do the Right Thing (1989) when it first came out. We’d been reading about the film for weeks before it arrived in the little Southern college town where we lived. Some critics were raving that this film was going to change the landscape of independent cinema, opening up the industry to other artists of color, and we’d also read the mouth-frothing and hand-wringing concerns of reviewers who worried that black people would run amok. My friends and I, living in lily-white East Tennessee, weren’t worried about that, though we would have liked the idea that a film could ignite that kind of reaction. We were smart and jaded enough to know that this worry was more an expression of white anxiety than any concern based in reality. We still wanted to see what the fuss was about. We had gone to Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) the year before when the religious nuts in our community had gone out to picket it. We were hopeful that something was happening in Hollywood, that perhaps the Lucas and Spielberg fairytales we had grown up with were being replaced by something with more substance, something that, even if it didn’t cause people to riot, might make them argue or yell.

Twenty-five years later, I can still see why some people were so intimidated by that film. The movie wasn’t willing to be ghettoized in a blaxsploitation genre subcategory; it wasn’t kitsch, and it wasn’t just entertainment, though it was entertaining. The movie dealt with serious issues like the brutal treatment of black citizens by white cops, especially the chokehold death of graffiti artist Michael Stewart and others. It cited both the nonviolent words of MLK and the militant “self defense” of Malcolm X and it didn’t say who was right. It showed a black community rioting – real three-dimensional characters who the audience laughed and sympathized with for the previous hour and a half – looking backward to the “long hot summer” of ‘67 and forward to the LA Riots in response to the Rodney King verdict. My friends and I knew that Spike Lee was interested in making films about a different kind of America than the Reagan narrative we’d been force-fed our adult lives, and we were hungering for those stories. In the first minutes of that film during the credits, some woman we didn’t yet know was Rosie Perez danced a dance of rage to the sounds of Public Enemy, a band we were all familiar with, ever since their brilliantly scary It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back had come out the year before. Public Enemy landed in that sweet spot between rap and punk sampling speed metal like Slayer and Anthrax and classic dance music like James Brown and Funkadelic. Like PE, Spike Lee was going to transgress easy genre lines. Was Do the Right Thing a comedy or drama? Entertainment or agitprop? Anti-white or anti-racism? Pro-violence or anti-violence? There were no easy answers.

It’s not taking anything away from Spike Lee to say that my friends and I were underwhelmed by his follow-up, Mo’ Better Blues (1990). Jazz seemed lame to us, old people’s music. And though we liked aspects of Jungle Fever (1991), it wasn’t Do the Right Thing. That’s probably the biggest criticism we would give any future Spike Lee film – or accolade – “His best since Do the Right Thing!” And though Do the Right Thing got “robbed” during the awards season – just an Academy Award nomination for best screenplay and beat out by Steven Soderbergh’s first feature, Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989) for the Palme d’Or at Cannes – since then, he’s won a special mention award at Cannes for Jungle Fever (edged for the Palme d’Or again, this time by the Coen brothers’ blackly comic Barton Fink (1991)), another special mention award at the Berlin Festival for Get on the Bus (1996), and two Emmys and a documentary award at the Venice Film Festival for his devastating Katrina hurricane doc, When the Levees Broke (2006) among many other awards and honors in his nearly forty-year career.

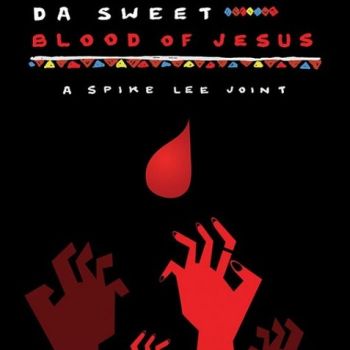

His new film is Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, a “re-imagination” (Lee’s term) of Bill Gunn’s 1973 vampire art film, Ganja & Hess, a more appropriate revision, probably, than his previous film, the American remake of South Korean director Chan-wook Park’s Oldboy (2003, remake 2013). Like Gunn, Lee has never been into exploiting the kitsch of African American culture embodied in the films that came out of Blaxsploitation in the sixties and seventies. Although Lee’s film is more accessible for a mainstream, or at least indie, audience, moviegoers will recognize in this remake Bill Gunn’s juxtaposition of natural imagery and the urban, the fusion of African folklore and European legend, the overlap of eroticism and extreme violence.

Spike Lee’s Brooklyn studio is on a block of million-dollar brownstones in the Fort Greene neighborhood. Beautiful wooden tables and chairs share space with folding tables and flat files. A shelf is packed with much of the racist toys and bric-a-brac that Damon Wayans’ bitter TV writer collects in Lee’s razor-sharp satire, Bamboozled (2000). On the second floor, expensive cameras on tripods (with signs that warn “Do Not Touch!”) are surrounded by walls sporting the framed movie posters for several of Lee’s films and also a few choice influences like John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969) or a signed Japanese poster of his fellow NYU alumnus, Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973). In this studio, around the corner from the historic BAM Theaters in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood which, just last year, played a two-week retrospective of his work, Spike Lee sat down with me for a few minutes to discuss the new film, Do the Right Thing, police brutality, and teaching.

John Duncan Talbird: I love your studio. It’s a cool place.

Spike Lee: I’ve been here for over 20 years.

JDT: I saw the new film, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, this weekend. It’s a remake of –

JDT: I saw the new film, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, this weekend. It’s a remake of –

SL: A re-imagination.

JDT: A re-imagination of Ganja & Hess. Can you talk a little about what drew you to the film?

SL: I saw Ganja & Hess, written and directed by the late great Bill Gunn, when I was in film school at NYU. And I’d always liked that film. It’s always stayed with me.

My students at NYU were the ones who told me about crowdsourcing. I’d never heard of Kickstarter. They were using it to finance their films. A bunch of my students were saying, “Well, Professor Lee, you should try it.” I did my research, met with the co-founders of Kickstarter, Perry Chen and Yancey Strickler, and they gave me a crash course in how not to fall on my face and fail. Because failure was not an option. Once I did that I had to think of a story that would fit within the budget. The goal was to raise one million, two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. We raised 1.4 and that is where the re-imagination of Ganja & Hess came from, which is now Da Sweet Blood of Jesus.

JDT: You co-credit Bill Gunn. Did you ever meet him?

SL: Briefly, at a screening of Ganja & Hess.

JDT: For this screenplay, you wrote this all by yourself, though.

SL: Bill Gunn’s been dead since ‘89.

JDT: I felt that the new film was really true to the original in a lot of ways.

SL: Oh, it had to be. I wanted to pay respect to the source.

JDT: Yeah, but it’s been updated in a lot of ways that I thought was really interesting. I love the scene at the HIV clinic where Hess goes to get tested. I thought that you did a good job of updating a lot of contemporary anxieties. Because the original film is set during the time of “free love.” I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit about what sets your film and Bill Gunn’s original film, in your mind, apart from traditional vampire movies.

SL: Bill Gunn did not consider Ganja & Hess a vampire film and I don’t consider Da Sweet Blood of Jesus a vampire film. There are elements of that, but that is something that both of us didn’t make.

SL: Bill Gunn did not consider Ganja & Hess a vampire film and I don’t consider Da Sweet Blood of Jesus a vampire film. There are elements of that, but that is something that both of us didn’t make.

JDT: I do think that you deviate from that. But even the character Ganja (Zaraah Abrahams) says, “So you’re a vampire?” and Hess (Stephen Tyrone Williams) says, “I’m not a vampire. I’m addicted to blood.”

SL: “I’m an addict.”

JDT: So even in the world of the film, they recognize that people that drink blood are vampires, correct?

SL: Yeah, but it’s not a vampire film.

JDT: Okay, but you play with some vampire tropes. Part of the film is set in a Church. Hess goes into a Church, despite the fact that he’s a vampire.

SL: Twice. At the beginning of the film and at the end. The church is called, The Little Piece of Heaven, Baptist Church of Red Hook. It’s the same church that’s in Red Hook Summer (2012).

JDT: And at the opening, it’s the funeral of Bishop Enoch (Clarke Peters) from that film.

SL: Not his funeral. He’s passed away. It’s not his funeral though.

JDT: Right before that, there’s a montage with the credits – which I thought was lovely by the way – the one that opens up the film, the dance sequence: Is that all set in Red Hook?

SL: Yes. That’s Lil’ Buck. He danced and choreographed all that.

JDT: How did you get connected with him?

SL: I saw him on Youtube, and then I saw him once again in the Michael Jackson show One in Las Vegas.

JDT: How do you see Red Hook Summer as connected to Da Sweet Blood of Jesus?

SL: Oh, they’re connected. You have the church, you have the character Deacon Zee (Thomas Jefferson Byrd) who’s taken over for Bishop Enoch. The church is the biggest connection. A major part of black history is embodied in the church.

JDT: It seems like the church is vital in the film especially since the last visit leads to the character Hess essentially giving up and facing death.

SL: He does make some decisions after going to the house of the Lord.

JDT: I’ve been thinking about it a lot since I watched the film. That last scene with Ganja and Tangier (Naté Bova) on the beach. It’s very…ambiguous. (Lee laughs.) It’s haunting.

SL: Well, you’ve seen my body of work before. I’m not being accusatory, but you know not everything has to be wrapped up in a nice little red bow.

JDT: I often show Do the Right Thing. I’m an English professor –

JDT: I often show Do the Right Thing. I’m an English professor –

SL: Where at?

JDT: At Queensborough Community College. And I –

SL: What’s the name of the class where you’ve shown the film?

JDT: I’ve shown it in “Film and Literature.” Last fall, I showed it in my Pop Culture class. I’ve shown it in my Freshman Composition class. Not in every class I teach, but if it’s relevant to what we are talking about.

SL: Thank you, thank you.

JDT: I love the film. And I find that it always leads to really rich discussion in class. And it hasn’t changed in its effect with students and I’ve been showing it for about fifteen years on and off.

SL: I bet one of the questions is “Why does Mookie throw the garbage can through the window?”

JDT: Yes. And if someone doesn’t ask it, I ask it. And of course, I ask, what is the “right thing”? And you know, I’ve read a lot about you over the years and I feel sometimes people think that you are making a heavy-handed statement here.

SL: I’ve been guilty of that.

JDT: Maybe, but I think that’s a really good film that embraces ambiguity. I find that predictable viewer reactions doesn’t break down easily along racial or ethnic or class lines about who is in the wrong or who is in the right in that movie. Some students say that Mookie shouldn’t throw the garbage can through the window. Some say that Sal is wrong, of course he should put the pictures on the wall. Some say that Buggin Out is creating a lot of static.

SL: Some say that Radio Raheem should turn down “Fight the Power.”

JDT: Exactly. It seems that ambiguity is very important in your movies, and the new film is not an exception. I’m wondering if this ambiguity is something you set out to explore, or if it’s more organic. There are no easy answers in a Spike Lee movie. Why are you interested in the ambiguous?

SL: It’s interesting! Let the audience finish the movie. I remember this like it happened yesterday. Do the Right Thing came out and lines were around the block. It was a problem, because the people coming out weren’t leaving the theater, they were staying in the lobby discussing the movie and they couldn’t get the people out front in for the next show.

SL: It’s interesting! Let the audience finish the movie. I remember this like it happened yesterday. Do the Right Thing came out and lines were around the block. It was a problem, because the people coming out weren’t leaving the theater, they were staying in the lobby discussing the movie and they couldn’t get the people out front in for the next show.

JDT: I think that’s the answer for why I show that movie over and over again.

SL: Here’s a question: Have you shown it since Eric Garner was killed?

JDT: That’s why I showed it in the fall – because of Eric Garner’s death. How can this still be happening twenty-five years later?

SL: What’d the class say?

JDT: Well, the students, of course, recognize that it’s an awful thing, that it’s a tragedy. They live here in New York. Many of them are of color.

SL: Do they know it’s based upon Michael Stewart?

JDT: They do because I tell them. They don’t know in advance; it’s ancient history to them.

SL: Anything before they were born is Neanderthal history.

JDT: Yes. For instance, today’s class, I asked my students about Katrina, only two students could say anything about it.

SL: Two?

JDT: Well, they knew about it, but, again, it’s history to them. They were ten or younger when it happened and it happened at the other end of the country.

SL: If I may suggest, you should show When the Levees Broke.

JDT: I’ve shown that in my class, too.

SL: The tenth anniversary is coming up.

JDT: I noticed outside your studio that you’ve got a list of all of your films on the door and you’ve got the fictional films and the documentaries separated.

SL: That was just done for the door as a way of organizing them.

JDT: So you don’t see a difference between the two different modes?

SL: It’s all story-telling.

JDT: Let’s go back to Da Sweet Blood of Jesus. The scenes alternate between some really erotic scenes and some incredibly violent and grisly scenes, and I’m wondering what effect you were hoping to generate. Because I know that a lot of vampire movies – and I know that this is not a vampire movie – but a lot of them eroticize violence. I felt that you weren’t doing that, that the violence was jarringly separate from the sex scenes.

JDT: Let’s go back to Da Sweet Blood of Jesus. The scenes alternate between some really erotic scenes and some incredibly violent and grisly scenes, and I’m wondering what effect you were hoping to generate. Because I know that a lot of vampire movies – and I know that this is not a vampire movie – but a lot of them eroticize violence. I felt that you weren’t doing that, that the violence was jarringly separate from the sex scenes.

SL: Here’s the thing: When you’re addicted to blood, there’s only so many blood banks you’re going to be able to rob, and when push comes to shove, you got to get that blood anyway you know how. People aren’t just going to slit their wrist or jugular vein on your behalf (laughs). And that’s what happens.

JDT: Why is it necessary for you to say that this is not a vampire movie?

SL: Bill Gunn said that, and I want to stay true to the original creator. I don’t know if you know the history, but some producers came to him who wanted to capitalize on the black exploitation film, Blacula (1972). And there was a very successful sequel called Scream Blacula Scream (1973). But Bill Gunn did not want to make a film like that, he went rogue and did something completely different from what the producers wanted and expected and they grabbed the film from him, chopped it up, released it under four different titles and thank god there was one uncut master and that’s the one that MOMA has.

JDT: That’s where I saw it a few years ago.

SL: That’s the only existing print at least in the way that Bill Gunn envisioned it.

JDT: I know that a lot of times that Ganja & Hess gets lumped in with Blaxsploitation films, but it’s an art film, an avant-garde film. It’s very challenging for the viewer.

SL: It’s “European.”

JDT: How would you see your re-imagining of that film as different? You’re trying to be true to the original, but in some ways there’s no point to remake a film unless you have something new to say.

SL: Well, I’m not going to be like Gus Van Sant who did a shot-by-shot remake of Psycho (1998). But there’s a way to be true to the source material, but have a different interpretation. Like when Julie Andrews sings “My Favorite Things,” John Coltrane heard it and made it sound different. When Miles did “My Funny Valentine” or when he did Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time.” It’s the same thing, but it’s different.

JDT: How did you get paired up with the stars for this film, Stephen Tyrone Williams and Zaraah Abrahams?

SL: I saw Stephen Tyrone Williams in the opening night of the Broadway play, Lucky Guy with Tom Hanks. He was amazing in that. And Zaraah was the co-star in one of my student’s thesis films.

JDT: You like teaching?

SL: Twenty years at NYU. I love it.

John Duncan Talbird is the author of the just-released, limited edition book of stories, A Modicum of Mankind (Norte Maar) with images by artist Leslie Kerby. His fiction and essays have recently appeared or are forthcoming in Ploughshares, Juked, The Literary Review, Amoskeag, REAL and elsewhere. An English professor at Queensborough Community College, he lives with his wife in Brooklyn.