by Matthew Sorrento.

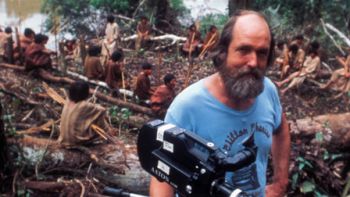

Naming Criterion’s new DVD/Blu-ray collection of films by Les Blank (1935-2013) Always for Pleasure was a given. In borrowing the name of Blank’s 1978 documentary on New Orleans, the set contains that film and several others radiating the feeling. Though Blank is known for his works with Werner Herzog – Burden of Dreams (1982), detailing the Bavarian director’s feat and obsession in making Fitzcarraldo (also 1982), and Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (1980), depicting the filmmaker making good on a bet once Errol Morris completed Gates of Heaven (1978) – and the latter film has the pleasurable feeling, at least in a traditional sense, more than the former. (Criterion included Eats as a supplement on its 2005 edition of Burden and 2015 edition of Heaven.)

With the release of Always for Pleasure box set, Criterion does a major service to the world of documentary film. Hard to film, these shorter works by Blank are now presented in the way that the late filmmaker wanted them to be seen. To assure this, his son, Harrod – an artist and filmmaker who took time out to discuss the set and his father’s work – filmed Les affirming his happiness to see the dirt and “hairs in the gate” gone from his films (discussed below). Now managing his father’s estate, Harrod helps to distribute Les’ catalog, while recently restoring and remastering A Poem is a Naked Person, an unseen Blank which premiered at the 2015 SXSW Film Festival and in July will premiere at New York’s Film Forum. (How to Smell a Rose, co-directed by Les Blank and Gina Leibrecht, will appear there in August.)

With the release of Always for Pleasure box set, Criterion does a major service to the world of documentary film. Hard to film, these shorter works by Blank are now presented in the way that the late filmmaker wanted them to be seen. To assure this, his son, Harrod – an artist and filmmaker who took time out to discuss the set and his father’s work – filmed Les affirming his happiness to see the dirt and “hairs in the gate” gone from his films (discussed below). Now managing his father’s estate, Harrod helps to distribute Les’ catalog, while recently restoring and remastering A Poem is a Naked Person, an unseen Blank which premiered at the 2015 SXSW Film Festival and in July will premiere at New York’s Film Forum. (How to Smell a Rose, co-directed by Les Blank and Gina Leibrecht, will appear there in August.)

Growing up with a father ecstatic as an artist but reserved in manner, Harrod embraced artistic rebellion and eccentricity. His first foray into art was creating art cars, outlandish, head-turning designs on vehicles. His creations led to his photography of them, which led to making films about the passion. Upon seeing his art cars in media, I think back to an excessively decorated house on the reserved Schanck Road, in my hometown of Freehold, NJ. (Though still best known as the birthplace of Bruce Springsteen, it has regretfully become Chris Christie country.) When my ten-year-old self asked my father, “Why does that house look like that?” my dad, who now resides in Tuscon – a drive away from one of Harrod’s homebases, Douglas, Arizona – said, “People like that make the world go around.” Les’ films have the pleasure of such eccentricity, and Harrod notes that his own rebellion, though a reaction to his father’s stoic manner, also embraces the spirit. Harrod even asked his father to assist him on a long-running film on Burning Man, which Harrod discusses below, along with his own films, preserving his father’s work, his aesthetic and filmmaking style, and his legacy.

I understand you are based in California and Arizona. Where are you in Arizona?

I’m in Douglas, AZ which, in its heyday, was one of the bigger, wealthier US cities. It had the copper smelting place; all the copper went through here. Then, it became like a ghost city and that’s why I came here and bought a building to turn it into an art car museum. So I’m down here in the middle, or more like the end of the world and I’m building this museum. I started it in 2005 and and prior to that I was living in a shack at my father’s house in Berkeley.

My mother died in that year, 2005, and she left me part of her house in New Orleans, and I used that to get this place down here. I’ve been commuting ever since back and forth between Arizona and Berkeley, CA and first worked on my own projects, which were Automorphosis (2009), a follow-up to Wild Wheels (1992), my first film, and now I’m working on an documentary on Burning Man. I’ve been filming Burning Man since ’93 and also helping out Les with his projects, and then he got sick in 2012, in April. I basically ended up going back to Berkeley and I stayed there pretty much that whole time, and then after he died started so working out of there. Now I’m pretty much more in Berkeley working for Les’ company and his legacy than I am in Arizona. So, my life is on hold for a second.

My mother died in that year, 2005, and she left me part of her house in New Orleans, and I used that to get this place down here. I’ve been commuting ever since back and forth between Arizona and Berkeley, CA and first worked on my own projects, which were Automorphosis (2009), a follow-up to Wild Wheels (1992), my first film, and now I’m working on an documentary on Burning Man. I’ve been filming Burning Man since ’93 and also helping out Les with his projects, and then he got sick in 2012, in April. I basically ended up going back to Berkeley and I stayed there pretty much that whole time, and then after he died started so working out of there. Now I’m pretty much more in Berkeley working for Les’ company and his legacy than I am in Arizona. So, my life is on hold for a second.

You lost both of your parents pretty closely; sorry to hear that.

Yeah, that was pretty brutal actually and they both passed from cancer metastasis. There’s nothing more brutal than a cancer metastasis death because it basically starves a person to death. It’s a very, very slow drawn out death. My mother said in a way it was a blessing to happen because she that she knew who really loved her and she could say goodbye to everybody she wanted to say bye to and all that stuff but I don’t know and I question what’s the better way to go pulling your teeth one by one slowly and, uh, it’s just horrible.

For Les the death process was especially difficult and painful because he loved living so much. You know, he was really hedonistic. He got everything out of life, enjoying it and, uh, to every degree and so it was very, very upsetting to him and to all of us that witnessed that, it was pretty brutal.

His films, especially those on the Always for Pleasure Criterion box set, feel like party media almost; they would work especially well shown at parties, or festive events.

He used to always tell me, when I was working on my own films, “don’t bring the audience down.” Make a movie that people want to watch and you can still move them and celebrate things rather than be a downer. That was really one of his backbone beliefs: to celebrate life and living and remember that “when you’re dead you’re dead – long live the living.” He swore by that quote.

That feeling shows up in a lot of his films.

Yes, Always For Pleasure, the box set’s title film is kind of another one of those back-home sayings of the man. That’s what he really believed. He really believed there was nothing else after death. He did not think there was anything else. So for him, life is it and that’s that. So that’s another reason why his philosophy of living at all times makes sense when you have that belief system.

Yes, Always For Pleasure, the box set’s title film is kind of another one of those back-home sayings of the man. That’s what he really believed. He really believed there was nothing else after death. He did not think there was anything else. So for him, life is it and that’s that. So that’s another reason why his philosophy of living at all times makes sense when you have that belief system.

I did film him, during this whole death process and I asked about death and I asked about living and a whole bunch of questions because, on camera, he would talk and, off camera, he wouldn’t really talk as much. So I learned basically to keep the camera going.

You see on the Criterion box set there is a short piece called Les Blank: A Quiet Revelation, made by Gina Leibrecht and me, who I’m working with now. We teamed up on doing this, so it’s possible that we’ll take on the death process, all the stuff that I filmed and intercut it with the life process. Gina focused on this because she did a lot of interviewing with Les in the last 15 years and maybe we’ll interweave the two to portray a deeper portrait of Les.

Do you think that, in part, the reason why he decided to be a filmmaker was to live on beyond his time? Did that motivate him as a filmmaker?

I never heard him say that per se, but I know that he revered the great works of other artists, especially in literature, when going with the death process. He loved Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. Les gravitated towards the classic artists and great works.

On the one hand, he didn’t think there was anything after life, but on the other hand, he did do a whole non-profit to keep his legacy going, so he really did care a lot about the condition of his films in the future after he’d be gone. He wanted to leave a mark on the world and leave great works, and maybe that meant to him a worthwhile life – being creative and making things and moving people was a big deal for him.

What is your impression of the Criterion set, now that it’s completed?

Well, it was a hell of a lot of work (for them), I’ll tell you that. I’ve worked with Criterion in getting a lot of the images and some of the interviews and, by the way, a lot of those images were never seen anywhere before because they were in boxes and he didn’t think they were worthy as he was dying. I looked at these pictures with him, made selections, and then they became the cream of the crop of the images Criterion ended up using in the pamphlet that comes with the box set.

Criterion also went back in and re-mastered the films. I didn’t really know what that entailed before working with Criterion. So I thought doing it myself on another film of Les’, called A Poem is a Naked Person, on which I’ll work with Criterion. So, I learned by doing that process of just how laborious it is, all the technical and attention to detail that is necessary for just one film.

Criterion also went back in and re-mastered the films. I didn’t really know what that entailed before working with Criterion. So I thought doing it myself on another film of Les’, called A Poem is a Naked Person, on which I’ll work with Criterion. So, I learned by doing that process of just how laborious it is, all the technical and attention to detail that is necessary for just one film.

It took me literally over two years to do A Poem is a Naked Person, to iron this out and get it all re-mastered and cleaned up and mixed and remixed and everything. You know, all the various things… and it’s still being worked on, as we speak, right now, and it still has some things that need to be worked on. But what I learned from the process is exactly what Criterion is doing for these films. It’s amazing the amount of work, money and, I’d have to say, passion because if they were really concerned about the bottom line and just turning a profit, they wouldn’t be spending this money and time on these films. But they are treating them as the classic works of art that they are. Criterion’s going to the end of the line to do it the best they can.

The films look better than they ever have looked. If you look at one of Les’ DVDs, the difference is night and day. Take Hot Pepper (1973), for example. If you watch what Les was putting out into the world on DVD, it’s horrible compared to what Criterion put out in the box set.

And, you know, Les was a film person; he was trained in film, and he was a very, very high quality guy. His filmmaking was his craft and he did his best he could, shooting on Super 16 even. When his films came out on film the prints looked beautiful, but as 16mm started to fade away and his business started to fade away he had to adapt to DVD and digital and all that. He didn’t really make the adaptation very well; he had to learn so much at an older age, and it overwhelmed him.

So, the Criterion release is sort of bringing Les’ work into the present digital age at a higher quality that is comparable to the original 16mm films. What I’m doing working for Les Blank Films, (http://www.lesblank.com/) which is a non-profit, is re-mastering the films that Criterion hasn’t or won’t re-master and to also release the never released films. I had to meet with Leon Russell four times before. Finally, we came to an agreement on releasing A Poem is a Naked Person.

So you will be working with Criterion on this film?

Criterion, I believe, well do some more cleaning up on it. I’ve already done the bulk of the work, the re-mastering, and the edit, to piece it together and try to adhere to what Les had in his final version.

As far as the current Criterion set goes, would you say, Hot Pepper needed the most work in restoration?

Hot Pepper needed a lot of restoration. I actually looked at the outtakes that were at the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY and they were turning purple. The fact that Criterion re-mastered them is really important; they’ve been working with the Academy Film Archive in Los Angeles, where Les’ films are stored. They had to get up to the Academy, transfer them to 2K and scan and conform them to the inner negative and then color-correct every single shot and then tweak the audio mix. It’s just….it’s all these little things that go into re-mastering a film. Their work is very significant.

It sounds like tedious work.

You know, it is pretty tedious; the attention to detail, is just significant because they’re doing things frame by frame and everything had to be matched perfectly, the film speed, the audio speed, all that stuff has to be perfect. The attention to detail, I would say, is the biggest part of that work – having quality people working with the entire process.

You know, it is pretty tedious; the attention to detail, is just significant because they’re doing things frame by frame and everything had to be matched perfectly, the film speed, the audio speed, all that stuff has to be perfect. The attention to detail, I would say, is the biggest part of that work – having quality people working with the entire process.

Criterion did Burden of Dreams and Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe first. Burden of Dreams was done in 2001 or 02, when they used the digital format called D5. Even since Burden of Dreams the technical aspects have changed a lot; the new Criterion box set is the contemporary way of doing this re-mastering and even scanning. The scanners are better, and they went from rough HD to full HD to 2k, and then there’s 4k. I just saw a commercial on TV that said the iPhone has come out with some with double 4k, and I’m like, “what, you can’t even see that!” In probably another five years the re-mastery process will be different.

We often think that when things went to digital and that was it, it’s complete in format, but it’s constantly evolving, isn’t it?

It’s very, very frustrating. Part of being a contemporary media person is to know what are the newest best formats there are and to try to use that and you have to know all the technical information. It’s just overwhelming and frustrating; the poor editors have to constantly update their software for editing like Final Cut which I think is in competition with Adobe Premiere. I edited my film on an Avid in 2009 and that Avid is completely obsolete now, pretty much. I had to relearn programs to use the new software, and then the new can’t read the old.

Wow, that does seem tough. People complain when they get a new version of Microsoft WORD….

Yes, exactly.

Since you mention Herzog, Harrod, do you think this new set’s job, in part, is to make people aware of your father’s work outside of the Herzog documentaries? Because he’s well known for them.

I don’t think so. They were focused on Burden and Herzog Eats in the beginning. I’m going to re-master Burden of Dreams again, and Criterion hopefully will release it as Blu-ray. The masters they made are good, but I think they could be even better, if they can scan at a higher resolution. But it would mean a boxed set, if anything, also including Burden or Herzog Eats, and probably some other films, too.

On Les’ website that I help run, www.lesblank.com, you can go see the titles outside the Criterion boxed set. We are also distributing films by filmmakers that Les liked. Plus, lesblank.com is a reseller of the Criterion box set.

Are Les’ other films available on DVDs, pay for download, or both?

Right now as DVD, but downloading, I think, will come one of these days. Les never had an intermediate, a middleman that operated between him and something like Netflix. Plus, he didn’t put them on Amazon; he didn’t believe that it was a good deal for him. Now, I’ve been reluctant to do it as well because I’ve been trained by Les as a film person. But now I will try to wrap my mind around adapting them as downloads. For some people, all they do is watch films that stream on Netflix.

Can you talk about how your father would approach difficult subjects and make them seem so simple? He seems to do this over and over and over again in his films.

I can’t really comment on that. I know that he gravitated to what he longed to go for, and what piqued his interest is what he wanted to go for. And that’s why the films are really about his passion, love of life, passion for people, for culture, an artist, or whatever the subject may be. Les would just go for it. Garlic is a great example; he loved garlic, and just wanted to make a film about it.

What a wonderful film, a real pleasure of a movie.

I know. He, do you realize that that film has had a pretty big influence on cooking? On people using garlic more? I wouldn’t say that it’s the biggest reason, but a contribution to the popularity of garlic in different dishes.

It seems like one of those things that people really love but are afraid to admit it, and then you watch the film with all those garlic buffs.

I can say the same thing about Gap Toothed Women (1987). These women may have been looked down upon, thought of as not as attractive, are suddenly the attractive ones. Les found gap toothed women attractive, and he liked garlic a lot, the reasons why he made those films. He felt the same about folk music and artist portraits. He was gonna do a movie on red headed women as well.

His taste in woman was very diverse. He liked a lot of different women, different types of women, different cultures. You see a lot of portraits of beautiful women throughout in his work. In Burden of Dreams you’ll see a ton of portraits of not just women, but of lots of people, ones he founds beautiful.

Would you say he was fascinated with ritual too?

Yes. He was interested in ritual. He wasn’t interested in religious ritual so much, though there is some religious ritual In Heaven There is No Beer? (1984) He was curious about other people’s religion but, he himself didn’t go to church and wasn’t really comfortable with church. I remember that he did do a scene in the Leon Russell film with a church gospel scene. He did film a baptism in A Well Spent Life (1971), because that stuff fascinated him: he had never seen that kind of thing in his life previous to that. One of Les’ many gifts was having a knack to be ahead of what he was shooting and to see beyond what he was shooting and then move the camera intuitively, poetically to the next thing.

Do you think he wanted to show a utopic vision in his films?

That’s a good question. He might have been pushing the envelope of what happiness is. I don’t know if it was Utopian so much as his investigating the philosophy of happiness.

Would you say he was showing people escaping capitalism and capitalistic patriarchy at all?

There is a connection between the everyday man, the working man, because Les wasn’t familiar with them at all – he grew up in an affluent family in Tampa, Florida. I think he revered them, that working the land was an honorable thing to do. But also enjoying life and celebrating life was obviously a big part of his philosophy.

How did he feel about the popular docs that have come out lately? And how do you feel about them too, for that matter?

Well, he wasn’t big on a lot of the environmental films that came out, and he didn’t like going to see a film that would be a total downer. I think he could handle a film like that once in a while. But when he saw The Act of Killing, he felt it to be manipulating. He didn’t talk about it a lot, but I know he had some issues with it.

Recently, when I was at the International Documentary Film Festival (IDFA) in Amsterdam, and when I went to the Independent Filmmaker Project (IFP) in NY there was a lot of talk from panelists, experts in the field, about how we need movies like The Act of Killing. They’re encouraging young filmmakers to push the envelope, as was done in the Act of Killing, and it kind of made you wonder what direction we’re going in.

That’s interesting that he didn’t like The Act of Killing because Herzog and Errol Morris were praising it up and down, left and right.

Yeah, I think Herzog and Morris were the ones who recommended the film to him, so he thought he would love it. Though he did watch it when he was dying, four or five months before he died, so he probably wasn’t feeling very happy about life anyway. He had so little energy to watch film – he might of watched one a day at the most, and probably just didn’t want a downer.

He felt that filmmaking had become watered down and less professional than how he was trained as a young filmmaker. I think that he was tired of watching things that didn’t move him and he was getting impatient with a lot of films that were being given him to watch. But he loved watching movies, overall – he was a judge in the documentary category for the Academy.

What was your first filmmaking experience?

I think it might have been A Poem is a Naked Person (1974). I was there with Les in Oklahoma, in 1972, when he was in the middle of making that film. I was immersed in that whole Leon Russell world at the Grand Lake of the Cherokees where they were based. And as far as working on a film, I worked on Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, assisting Les, carrying the camera, and stuff like that. On Garlic is As Good As Ten Mothers I was actually in the film talking about dysentery and how garlic cures dysentery.

That’s you?!

Yeah. (Laughs) In Mexico I got dysentery and the doctor said drink fresh orange juice with a whole boat-load of garlic and do it constantly all day long and you’ll do some damage to the amoebas and whatever. It didn’t cure me completely but it certainly helped. Les remembered that experience and wanted to film me talking about it and that’s how I ended up in there.

Though looking back I didn’t really want to be a filmmaker in the beginning. I wanted to be a writer. Then when I was in college a few years back and went to Mexico my junior year, I wrote all this stuff in Spanish that had to be translated to English. I just sort of excelled in film class and everything because I grew up with Les telling me his thoughts on filmmaking. He bought me a camera at 17 and said that I should get to know it and know how to use it, but what I really should do is make it see like your eyes see. In other words, I should hone my vision how to see. And so I thought that was interesting. And I got into art cars, making them in college, and doing art car photography in a book. Then came the documentary Wild Wheels, which was a National Special on PBS. That really tickled Les because none of his films were shown as national specials before.

And I gotta say, you know, I was always the son of Les Blank, all growing up, all through college. Then with my first film and then after I made Wild Wheels, Les started being called the “Father of Harrod Blank.” It led to kind of a father-son competition. I had to be obnoxious to get his attention when I was younger, because he was so stoic. He wouldn’t share a lot of his feelings or affection, so I had to pull it out of him. You could argue that the whole art car thing, for me, was to get my father’s attention.

And you are currently working on a documentary on Burning Man?

I had Les work with me on an epic Burning Man film. I’ve been at work on it for 22 years. I would give Les a camera to shoot it and 20 rolls of film; he would just go out and shoot whatever he wanted, but the footage he brought back was iconic Burning Man imagery, the way people dressed, the way people were having conversations and being intimate – the daily life at Burning Man. Another one of his talents and gifts was to intuitively know what was important about a place and culture, what was significant, what he should shoot, what would resonate and be meaningful, what would describe that place and that culture. I’m looking forward to its completion.

How have his films benefited from digital transfers?

With digital, you can actually make the film better then it was in the beginning, because of what’s called DRS, which is digital restoration service, software that allows you go into the film frame by frame and correct the frames. If a white dust particle is in a shot in one frame and not in the next frame, the computer program will automatically read that and automatically remove it by filling in the actual pixels by what was behind the white dot in the other frame. It matches it so you cannot see the difference.

I was just learning about this when Les was sick, and I asked Les on camera, “Would you want your films to have the white specks removed?” and he said, “Yes, I hate them.” He always wanted to get rid of that stuff and he couldn’t. The other thing that you can do with this re-mastering process, digitally re-mastering, is that you can play with the contrasts, you have more control to change the contrast, the saturation. With digital you have much more control over making a better quality image. Les loved digital, and would have loved to see the Always for Pleasure box set.

Matthew Sorrento is Interview Editor of Film International. He teaches film and media studies at Rutgers University in Camden, NJ and is the author of The New American Crime Film (McFarland, 2012). He directs the Reel East Film Festival.