By Hooman Razavi.

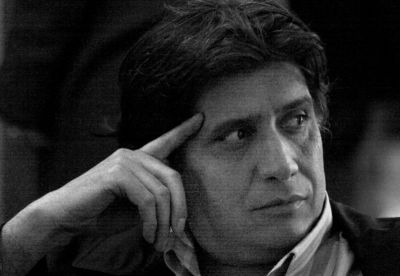

Since February 2015, producer Mostafa Azizi has been detained in Iran’s notorious Evin Prison (when visiting an ailing parent) on a bogus charge of endangering national security and insulting the supreme leader. Azizi is sentenced to 8 years and is now waiting for an appeal, supposedly to be held soon. As one who knew him for a couple of years and interviewed him on the topics of Iranian cinema, means of alternative film production, and the issue of censorship (transcribed below), his detention is a testimony to the flaws of Iranian system and his and other artists’ battle against ignorance and forces who want to silence dissent and creativity at all cost in Iranian society.

Azizi had been active in art circles in Iran and the diaspora for many years. He started his career as a producer, first in Iranian radio and television, and then founded his own film company producing television series, short films and animations. Since 2010, following his immigration to Canada, he has been involved in filmmaking and helping Iranian talents reach their potential through his Toronto based company, Alternative Dream Production.

Could you elaborate on the status of Iranian independent cinema in the last decade?

As you may know, all the feature films in Iran have to pass the filter of the Ministry of Islamic Culture before being screened publicly; similarly, all TV programs must follow the same procedure to get a pass from the TV department responsible for controlling content. As a result, neither scripts nor films are made without the authority’s consent: there is no “independent” cinema in Iran.

Having said that, after the presidential election of a reformist president in Iran in 1997 and the opening up of the cultural scene, the prospect, especially for production of short films, was looking up. There were fewer restrictions; a space was created for these producers to bypass the censorship and turn these short films into long feature films. At first, they were distributed widely outside of Iran, but then later, they were sold in the local market in the form of illegal CDs.

Obviously, not all of these films faced the same fate. Some were produced, but later confiscated, while others were halted at the outset. A few others, like Mehrjoui’s popular Santouri, were financed enthusiastically by various people, though the government tried to stop this practice. Among the unnoticed and unscreened films that I have been privileged to watch was Bitter Sleep by Amir Yousefian; the quality of this film, like many other independent films, has never had a chance to be recognized.

How are independent films funded and distributed in Iran?

In response to your funding question, as I said, there can’t be any independent funding. Most financial deals and loans go through private companies or banks with the approval of the authorities, though some approved projects will later be censored.

As for distribution, there are private networks, now well established, that distribute CDs and DVDs of films which are not permitted to be screened publicly. There is also a new trend; companies like Telefilm are distributing these films to private stations.

How do independent filmmakers recruit crew members and actors?

Recruitment is fairly easy. I have to say that apart from many well-known film stars who may charge a lot to be part of a film, most professional film people will work in large independent films as well as in more commercial films, as long as they know who is behind the film; they may not demand a large salary. So the personnel pool is pretty stable.

In addition, as I pointed out about Telefilm and small companies, often based in private homes, which are popping up recently, this distribution is attracting filmmakers and crews to the industry because money is flowing and it has become possible to make a living by participating in it.

How do you see the difference between Iranian mainstream and independent cinema and how are they interdependent?

Well, I have to ask you to define what you mean by “ independent cinema.” To me,”independent” implies more about the audience and the popularity of these films. Calling a film “independent” does not depend on whether or not it is screened and financed officially or independently. In fact, this term in the Iranian context is quite different from what Hollywood conceives of as “independent.” Many so-called “independent” filmmakers like Kiarostami get funding from the government.

In Iran, the government prefers not to censor artistic films or theatre productions; it even supports them because they as they bring recognition to the country. Ironically, this is an expensive undertaking for government, but on the other hand, it puts heavy regulations on films which have popular support, like TV productions.

Who is the main audience for Iranian independent films?

If you are referring to artistic and intellectually stimulating films, their fan base is quite limited: the intellectual segment of Iranian society and the Iranian diaspora. The more entertaining, mainstream films that get distributed through Telefilm have a wider audience of average people who access these films through cable, local stores and other channels.

How has the process of making independent films in Iran changed since the revolution in 1979?

I should say that in the last few years leading to the revolution, the cinema — including Independent filmmaking — was in freefall, and Hollywood films flooded the Iranian market: I remember watching many of them in dubbed versions, which were very well done, soon after their release.

After the revolution, this link to American Hollywood products was cut off and an indigenous cinema began to develop which, though good for its independence, but not very progressive from my point of view. And now what we are witnessing is the return to the old years of the 1970s in which Iranian entertainment films are being made again, albeit with a different flavor. Subtitled American films and popular TV series are also back in the Iranian market, but sold only in the streets and underground.

So basically, we see that just as Iranian independent cinema was under pressure from Hollywood and other sources before the revolution, it is now competing again with the same forces and, in addition with many other low quality films from countries like Mexico, Turkey, and Korea. These are shown on the many channels available to Iranian audiences and are gaining much popularity.

What other obstacles do independent filmmakers encounter in turning their ideas in reality?

Apart from governmental obstructions, I feel that the cultural hegemony of the current system influences both the people’s and the filmmakers’ mindsets. I can see a backlash coming from people ignoring the Iranian broadcasting agency and turning to other channels to watch films and, as far as I know, forming film clubs. The main issue seems to be getting the finances and logistics together without government aid or interference and then connecting with a wide, young audience that that is already bombarded with so many available diverse films.

What general themes are usually portrayed in independent films in Iran?

From my observations attending the Eastern Breeze and other Iranian short film festivals in the last two years, I would say that most films tend to focus more on the aesthetic aspects and are formalistic in order to avoid censorship. As such they try to distance themselves thematically from the touchy social issues. Obviously, there are some exceptions — films that do portray sensitive issues. The good one I remember was a film about a young girl who gets deflowered and no hospital in Tehran would accept her; this forces her into a very tough physical situation.

Do you have any further comment to share with us, anything missed during our discussion?

To me, the main concern is the independence of Iranian cinema; how can it make decisions on its own. I could compare its status with Iranian literature and its writers’ association, which always stood against government censorship and orders. I would argue that because Iranian cinema personnel is part of the Iranian bourgeoisie, which is led by government, its cultural products and decisions are dictated and controlled by that government aligned with the ruling class, making its independence virtually impossible.

Hooman Razavi has conducted several interviews with Iranian cinema personnel and translated works on other topics, including political science and history.