A book review by Tony Williams.

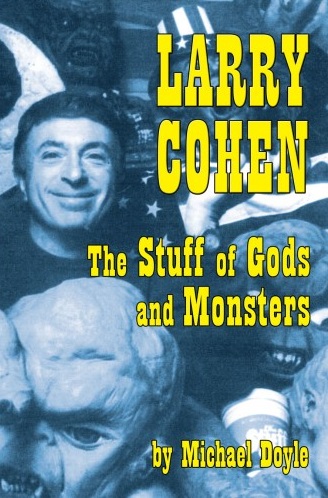

Those fortunate enough to have met or interviewed Larry Cohen are always amazed by his detailed answers to questions as well as his unique knowledge of American cinema and history. Michael Doyle’s Bear Manor Press publication is the most detailed compilation of interview material that has so far appeared. Extending to a generous 699 pages including credits, select bibliography, and detailed notes (necessary since most readers may not have the requisite historical information) this book is an impressive achievement matching the 1986 Cahiers du Cinema compilation Il Etait une Fois…Samuel Fuller that still awaits translation today. Thanks to Cohen’s characteristic generosity Doyle has managed to elaborate on issues that word constraints of most publications have limited and also included new material. It is an impressive work heralding a uniquely creative talent whose confinement to low-budget cinema has not prevented his own concept of film authorship from prevailing and achieving the recognition it so sorely deserves.

The interviews themselves occurred during a three year period from June 2011 to September 2014 with supplementary phone calls during that time to corroborate information and add further details. They cover Cohen’s early life to the present day with two photo sections containing some never before seen stills generously supplied by the director himself. Containing foreword by collaborator and friend Laurene Landon, introduction by Mick Garris (who needs to be reminded that other books have been written about Cohen), and generous blurb comments by Dave Alexander, John Landis, Joe Dante, and John Hancock, the interview material copiously reveals why Cohen is the innovative genius he continues to be today despite his neglect by a film industry sorely needing his input fully deserving his comment, “Modern cinema is homogenized and bereft of originality. Nothing around interests me very much.” (472)

Inspired by Hitchcock, with whom he collaborated with earlier, Cohen reworks his mentor’s mode of suspense with a comedic undercurrent that is uniquely his own. Cohen is also a founding figure of American commercial guerilla filmmaking and the information he supplies about working on a low-budget, using locations, and cutting corners (126) in Hell Up in Harlem (1973) evokes similar methods employed by Orson Welles documented in another mammoth interview book, This is Orson Welles (1998) and confirmation by collaborators such as Keith Baxter. Significantly, Cohen mentions that Samuel Fuller’s character in A Return to Salem’s Lot (1987) was based on Edward G. Robinson’s Wilson in The Stranger (1946). Low budget film making conditions the type of material available but not different forms of creativity as Cohen’s films demonstrate.

Cohen’s works operate as radical allegories of American society opening doors that official gatekeepers prefer shut as his detailed comments elaborate here. Fully aware of how the American film industry perversely works (see 317-321, 328), he is also skeptical about the medical industry, the unhealthy food industry, and the devious manipulations of the political system. Cohen’s comments on the flaws of Eastwood’s J. Edgar as opposed to the detailed historical research he undertook for The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977) leaves no doubt in the reader’s mind which film will last the test of time as long as Cohen’s style and structure is understood properly. As Cohen states, J. Edgar is “the gay man’s version of J. Edgar Hoover” (203) lacking the scrupulous verification of detail that characterizes his own film. Bone (1972) is a film containing accurate nuances easily recognizable to black audiences rather than whites that soon became misunderstood and the victim of misleading advertising promotions. (104)

Cohen is also the ultimate auteur easily fitting the original formulation of the term by Cahiers du Cinema and Movie (105, 251) as well as someone whose screenplays express that very different definition by Gore Vidal of the script representing the essence of the creative process. Those familiar with the ten unfilmed screenplays available on Cohen’s Web Site cannot be but impressed with the vitality of the writing as well as saddened by the way that certain scripts have been betrayed at the hands of lesser directors who cannot match nor understand the distinctive nature of material that could have made their films much better than they eventually turned out to be. Alert to the contradictions of everyday life as well as being aware of how few films manifest these elements (161-162) the films of Larry Cohen at least attempt to instill awareness in viewers in different generic forms of which comedy and dark humor reign supreme. His comments on the medical industry depicted in works such as It’s Alive (1973) and The Ambulance (1990) reveal a grim awareness of the institutional dangers behind a profession that has been so unthinkingly glamorized in many films and television productions. (464-465) In one way or another his works reveal the insights of an historically aware director that even though may appear in a film he scripted and expresses dissatisfaction with its technical realization such as Uncle Sam (1996) still resound with relevant elements unseen in any contemporary American film of its time (361-363) His comments on the Maniac Cop screenplays poorly realized by the same director reveal a stunning awareness of the institutional and racist aspect of the American police that few films have treated and have a deep relevance to what is going on in America today. (409-410) As I’ve written elsewhere in Asian Cinema, it is so gratifying to see Cohen regard “the Chinese version of Cellular….being) “in some ways superior to the American version.” (520 ) This is another version of a different type of authorship existing in the story and becoming available to a director and scenarist who, naturally will adapt the original but at the same time respecting its premises in a manner the American version clearly did not.

Cohen is also the ultimate auteur easily fitting the original formulation of the term by Cahiers du Cinema and Movie (105, 251) as well as someone whose screenplays express that very different definition by Gore Vidal of the script representing the essence of the creative process. Those familiar with the ten unfilmed screenplays available on Cohen’s Web Site cannot be but impressed with the vitality of the writing as well as saddened by the way that certain scripts have been betrayed at the hands of lesser directors who cannot match nor understand the distinctive nature of material that could have made their films much better than they eventually turned out to be. Alert to the contradictions of everyday life as well as being aware of how few films manifest these elements (161-162) the films of Larry Cohen at least attempt to instill awareness in viewers in different generic forms of which comedy and dark humor reign supreme. His comments on the medical industry depicted in works such as It’s Alive (1973) and The Ambulance (1990) reveal a grim awareness of the institutional dangers behind a profession that has been so unthinkingly glamorized in many films and television productions. (464-465) In one way or another his works reveal the insights of an historically aware director that even though may appear in a film he scripted and expresses dissatisfaction with its technical realization such as Uncle Sam (1996) still resound with relevant elements unseen in any contemporary American film of its time (361-363) His comments on the Maniac Cop screenplays poorly realized by the same director reveal a stunning awareness of the institutional and racist aspect of the American police that few films have treated and have a deep relevance to what is going on in America today. (409-410) As I’ve written elsewhere in Asian Cinema, it is so gratifying to see Cohen regard “the Chinese version of Cellular….being) “in some ways superior to the American version.” (520 ) This is another version of a different type of authorship existing in the story and becoming available to a director and scenarist who, naturally will adapt the original but at the same time respecting its premises in a manner the American version clearly did not.

Naturally, Cohen does not want to dwell in detail on the sad travesty of a screenplay that became the Captivity (2007) when the project went out of his control nor like George Romero does he have much time for” torture porn” (522-524). His comments on the relationship of the complicated parallels between his Cast of Characters screenplay and Alan Moore’s graphic 1999 novel that became The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003) are worth considering especially in view of Stephen Bissette’s review essay in “Cohen’s Creatures,” Monster! 21 (2005): 93-94, and this should lead to further debate on this already complicated subject. For my part, I still stand by what I said in the second edition of my book in the light of reading Cohen’s fascinating screenplay also available on his Website. His generosity is not often rewarded as the circumstances behind getting the payment to a deceased co-writer’s family documents. (524-556)

Why is he not directing any more films?

The circumstances behind his involvement on the “Pick Me Up” episode of Masters of Horror 2005 episode reveal certain reasons as do his other negative experiences in the industry. Eloquently stated facts occur at the end of the chapter on this project.

“With me, on my movies, I do what I damn well please. That’s the way I want to make my pictures. If I can’t make them my way, I don’t ever want to make movies at all. I must be in absolute control of a film. I must have the freedom to improvise and make up new material and have some fun with it. If that is taken away from me, I simply can’t work.” (544)

There are virtually no areas in Hollywood cinema that would grant him this freedom today so his creativity is currently limited to the writing at which he excels. (545-561)

Unfortunately, certain errors occur that more meticulous copy editing could have avoided and which will be corrected in later editions. Henny Youngman is the better known first name of this comedian not “Henry” (35) and should not “vicious” be substituted for “viscous” since I do not recall the character in Return of the Seven resembling a Blob? “Regan” (86) should read “Reagan”. Walter Brenna does not play Ike Clanton in My Darling Clementine (1946) but his father (528) and “Gene Arthur” is” Jean” Arthur (437). Ray Kellog was not sole director (623) of The Green Berets (1968) but co-director with John Wayne.

However, these are all minor and do not detract from the magnificent achievement of this book in supplying the most comprehensive and detailed interview material with one of the unjustly marginalized and neglected figures in American cinema who deserves better recognition than he has received so far. If there is one book I would unhesitatingly recommend for a Christmas present this is the one.

Tony Williams is Professor and Area Head of Film Studies at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale and author of Larry Cohen: The Radical Allegories of an American Filmmaker – Second Edition (2014).