By Christopher Sharrett.

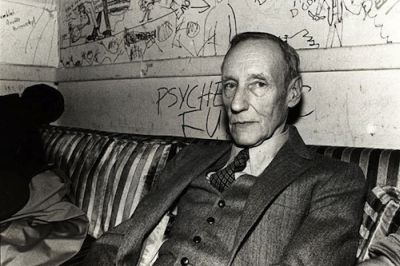

William S. Burroughs is often regarded as the King of the Beats, the central figure of the Beat Generation who mentored Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, telling them what books to read. Or he is seen as the ultimate loon of American literature, shooting and killing his wife and abandoning his son to live the life of a gay heroin addict in places like Tangiers, London, the Lower East Side of New York, finally Lawrence, Kansas, the site of a pre-Civil War genocide. In his later years, Burroughs, always emaciated, was the stooped Grandfather from Hell, his very identifiable, slightly nasal croaking voice like John Wayne on a heavy tranquilizer. In the 70s and 80s, he was everywhere on the media scene, talked about by straight pundits as the literary scene’s last bad boy, a toxic waste dump of narcotics abuse and sexual degeneracy. There are contrary views that demystify him, like the film Kill Your Darlings (2013), which portrays Burroughs as one spoiled (if demented) college kid among many.

Few modern writers have penetrated as deeply into popular culture as Burroughs, whose image is in the famous collage of “people we like” on the cover of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The rock bands Steely Dan and The Soft Machine take their names from Burroughs’s novels. Burroughs phrases are scattered throughout rock. Lou Reed, David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, and Mick Jagger have all gained cred with the cognoscenti by meeting with Burroughs. Although he kept a somewhat lower profile, Burroughs, like Ginsberg, transferred from the Beats to the hippie generation, taking part in the epic 1968 protests at the Chicago Democratic National Convention. There is an argument that drug terms like “fix” and “junky” entered the mass lexicon because of Burroughs’s novels and magazine articles as much as the drug use of the 60s counterculture and its co-optation by Madison Avenue.

Burroughs: The Movie by Howard Brookner, the first (and still best) comprehensive documentary about the writer, was considered by some a lost film (not I – my memories of the film’s premiere are clear, and I got a VHS copy of the film when it became available). The film has been in serious disrepair rather than lost, restored here by Criterion in a fine Blu-ray that enhances the film’s clarity while retaining all of its on-the-fly grunge. Made over five years, Brookner gained Burroughs’s confidence, allowing him to follow his subject from his residence at the Bunker, a former YMCA on New York’s Bowery, to his final residence in a little house in Kansas. While at the Bunker, Burroughs’s fame spread very fast. We go inside the Bunker, a place most of us would find a hard time calling home sweet home, with his dank stone interior and locker room adorned with dirty, ancient urinals. A large wooden conference table serves as the place where Burroughs both dines and receives famous guests.

Beginning in the 70s, Burroughs gave numerous readings to large audiences (usually with the help of pills and alcohol), arranged by James Grauerholz, his one-time partner who became his caregiver and literary agent, and who now runs the Burroughs estate. In what some see the strangest media event ever, Burroughs appeared on Saturday Night Live, hosted by fashion model Lauren Hutton. Burroughs becomes a superstar, appearing at the famous Nova Convention, where the cheering, packed audience goes wild with the first syllable of his strange, ominous voice. His status as godfather of all adversarial culture is confirmed by the end of the decade.

Beginning in the 70s, Burroughs gave numerous readings to large audiences (usually with the help of pills and alcohol), arranged by James Grauerholz, his one-time partner who became his caregiver and literary agent, and who now runs the Burroughs estate. In what some see the strangest media event ever, Burroughs appeared on Saturday Night Live, hosted by fashion model Lauren Hutton. Burroughs becomes a superstar, appearing at the famous Nova Convention, where the cheering, packed audience goes wild with the first syllable of his strange, ominous voice. His status as godfather of all adversarial culture is confirmed by the end of the decade.

Brookner lets us see some of Burroughs more off-putting hobbies, including his love of guns and other weapons. In a trip to the Bunker, we see Burroughs wielding a particular lethal blackjack, and firing an enormous blowgun at a piece of wood. In Kansas, Burroughs fires large-caliber handguns that almost knock him over. Some of the gunplay includes shooting at paint bags nailed to pieces of wood; what results are his famous splatter paintings that today may go for thousands. The gunplay reflects the Burroughs who loves boys’ adventure literature, which informs his later, more straightforward narratives like Cities of the Red Night and The Place of Dead Roads (the latter a kinky take on the western). These books also reveal Burroughs as one of our best satirists, as he takes apart the conventions and catchphrases of male-oriented genre art.

Burroughs gives us a crash course in his famous cut-up technique, the methodology informing his stream-of-consciousness novels like Nova Express (1964) and The Ticket that Exploded (1962). Burroughs takes a newspaper page, cuts it down the middle, then vertically. He rearranges the pages to produce new sentences and new meanings, on the theory that the random restructuring of information “lets the truth leak through.” Burroughs basically transfers collage from painting to literature, although his early novels are effective, to my mind, only after you hear him read them (as he does here – and there are numerous CDs around). His real emphasis is on how the mediascape creates a new, often fractured consciousness. Hearing him read Nova Express is like playing with the dial of a radio, listening to bits and pieces of broadcasts, music, and ads, suggesting to the listener a deranged brave new world.

There are some sad, even unnerving moments in Brookner’s film, such as a return to St. Louis, Burroughs’s birthplace, where we meet William’s brother Mortimer, a middle-America man not comfortable talking about most of his sibling’s interests – and especially his sexuality. Back in New York, Burroughs is visited by his son William Jr., a clearly disturbed young man who wrote the interesting novels Speed (1970) and Kentucky Ham (1973) before his death at age 33. James Grauerholz talks candidly about Billy’s resentment of James, who was treated more like a son than his actual offspring.

There are some sad, even unnerving moments in Brookner’s film, such as a return to St. Louis, Burroughs’s birthplace, where we meet William’s brother Mortimer, a middle-America man not comfortable talking about most of his sibling’s interests – and especially his sexuality. Back in New York, Burroughs is visited by his son William Jr., a clearly disturbed young man who wrote the interesting novels Speed (1970) and Kentucky Ham (1973) before his death at age 33. James Grauerholz talks candidly about Billy’s resentment of James, who was treated more like a son than his actual offspring.

Brookner includes black-and-white footage taken in the early 60s, showing a younger Burroughs looking a good deal like the older, fooling around with friends like Ian Sommerville and Brion Gysin. Burroughs always credits Gysin with creating the cut-up technique; this may be entirely true, but it was Burroughs who brought the technique fame and put it to good use.

Burroughs: the Movie covers the bases of the writer’s life and art, but because it was made a tad early it doesn’t catch the Burroughs apotheosis in the 90s, which continued as Burroughs continued to read and make recordings until his death in 1997.

The hero of this restoration is Brookner’s nephew Aaron, who oversaw the film’s restoration and the creation of the Blu-ray, Howard Brookner having died in 1989 at age 34, a tragic loss.

I have my own Burroughs story. I was in La Guardia Airport in 1986. I spotted James Grauerholz standing by a gate area. If Grauerholz is here, can Burroughs be far behind? I approached Grauerholz nervously; he graciously took me to where Burroughs was seated. Not wanting to talk about my favorite moments in his novels, I brought up the topic of firearms – I was raised in the gun culture, albeit a very different one than the loony rightist formation of today. We talked about the virtues of the .41 Magnum over the .44, whether the .9mm is a good defensive weapon, and the problems of the valorized semi-automatic pistol over the revolver. We were on the same plane – they were returning to Lawrence, I was headed for a conference at the University of Kansas, where I rendezvoused with a woman I married. Burroughs gave me his boarding pass and business card. Quite a trip.

To me, Burroughs is not just the leading Beat but a major figure of the youth counterculture I once knew. Burroughs is now gone, along with the most of the great landmarks of the East Village, always the heart of the postwar counterculture, the better to make room for franchise stores. But one can give the world of gentrification the finger, just as Burroughs did to bourgeois life in general. Burroughs: The Movie helps prompt the impulse.

Christopher Sharrett is Professor of Film Studies at Seton Hall University. He writes frequently for Film International. His recent essay on H. P. Lovecraft and horror cinema appears in the recent Cineaste. He is currently listening to three remarkable piano variations performed by Igor Levit. They are Bach’s The Goldberg Variations, Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, and Frederic Rzewski’s The People United Will Never Be Defeated! Bach in the Goldberg offers us what might be called the story of a life; he reminds us, as Robin Wood remarked of Mozart, of what we have lost and will not be recovered in the current epoch. The Beethoven shows the presence of Bach, but in a surprisingly light-hearted work with a minimum of the Beethoven pomposity. The Rzewski responds to Bach, telling us exactly where we are, his variations a call for revolution as well as a commemorative piece for the people of Chile, who suffered so terribly under the 1973 U.S.-backed military coup against the democratically-elected socialist President Salvador Allende. These variations are often atonal, discordant, and aggressively eerie, modernist with its most challenging associations, punctuated with various melodies and anthems, as the human spirit fights the chaos caused by the capitalist world. In the liner notes, Rzewski asks necessary questions: “Am I allowed to live in my ivory tower? What, in fact, am I doing? And what sort of life am I living?”