By Tony Williams.

Critic-director Stig Bjorkman, well known for his studies on directors such as Woody Allen and Ingmar Bergman, has made an intriguing documentary on this well-known star to which he has also collaborated on the screenplay. Most documentaries either concentrate on abundant clips from films already well known or utilize publicity material concerning the star’s celebrity persona either positively or negatively. By contrast, Bjorkman has chosen another approach, one that utilizes the copious home movie and photographic footage covering Bergman’s life as well as extracts from her diaries and letters, read often in Swedish by Scandinavian actress Alicia Vikander. It also features members from Bergman’s family such as Pia Lindstrom, the three children by her second marriage to Roberto Rossellini, and working colleagues such as Sigourney Weaver and Liv Ullman who speak positively about the impression this actress made on them. While Bergman is already the subject of several fine essays by Andrew Britton and Robin Wood, Bjorkman pioneers a unique way of understanding the actress’s private and public personae by emphasizing the role home movies played in her life whether she is behind or in front of the camera. As the film shows, Bergman was preoccupied by the photographic still and cinematic image, and she aimed to control it as much as any of the celebrated directors she worked with. Beginning with a photo of the young girl in April 1928, praying to God to save her father who would die of cancer a year later, followed by a photo of her with her beloved parent, an extract from her diary follows – “I want to write down everything that happened to me in 1927.” Losing her two other siblings at an early age and a mother she never remembered, she traveled alone to Germany to visit an aunt ending her entry with the poignant “All I want is a Happy New Year.”

Limiting feature footage of Bergman to the bare minimum, this creatively inspired documentary concentrates on home movies showing the actress with her family at various stages of her life. One series of photographic images shows Bergman either on set or in a crowd using different types of cameras whether 8mm, 16mm, or 35mm filming either her present surroundings or activities on the set but often images of a family she enjoys being with for a particular cinematic purpose that will remain with her forever. One of the poignant letters read out by Vikander is one Bergman wrote to her estranged husband, Dr. Petter Lindstrom, asking him to send her photos of her father and her daughter Pia, but also realizing that the huge amount of 16mm home movie footage he possessed could wait: “One day I’ll ask for all my treasures.” These treasures are now housed in the Ingrid Bergman Archive at Wesleyan University.

Limiting feature footage of Bergman to the bare minimum, this creatively inspired documentary concentrates on home movies showing the actress with her family at various stages of her life. One series of photographic images shows Bergman either on set or in a crowd using different types of cameras whether 8mm, 16mm, or 35mm filming either her present surroundings or activities on the set but often images of a family she enjoys being with for a particular cinematic purpose that will remain with her forever. One of the poignant letters read out by Vikander is one Bergman wrote to her estranged husband, Dr. Petter Lindstrom, asking him to send her photos of her father and her daughter Pia, but also realizing that the huge amount of 16mm home movie footage he possessed could wait: “One day I’ll ask for all my treasures.” These treasures are now housed in the Ingrid Bergman Archive at Wesleyan University.

Bergman was no Charles Foster Kane obsessively collecting everything without any real knowledge why. She intuitively knew the reason and was never haunted by any undecipherable “Rosebud” syndrome. For her, the footage represented an essential part of her life capturing moments she knew were transitory but which she wanted to return to continually as she remembered the brief time she had with a father who inspired her to become an actress. Several photos show the young daughter with her beloved father at a poignant moment, while home footage taken of the two-year-old Ingrid with father reveal them placing a wreath on her mother’s grave, a mother she never really knew.

Despite traumatic losses, Bergman retained a sense of independence and resilience throughout her life. Though her surviving children all testify to her role as a loving mother and warm-hearted person, Ingrid Bergman was a free spirit with a sense of wanderlust who never became rooted in any one place whether artistically or geographically. As she stated in a late interview, “I don’t want any roots. I want to be free” when remarking on her ten-year sojourn in Hollywood after leaving Sweden where she never intended to remain. Eight years in Italy and then twenty years in Paris followed with her final years in spent in London, where she died. Claiming her independence following vilification in America once her affair with Roberto Rossellini became known, she states, “No one but I can decide how to live,” affirming that her private life is her own. Acting was her life. “If you took acting away from me, I would stop breathing.” Her diary entry records concern not working immediately after Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) with a four month delay before Casablanca (1942), starring, of course, Humphrey Bogart, who was not the typical Hollywood “glamor boy.” She describes frustration with this period of forced inactivity, despite being with her family, making her feel that “only half of me was alive.”

Despite traumatic losses, Bergman retained a sense of independence and resilience throughout her life. Though her surviving children all testify to her role as a loving mother and warm-hearted person, Ingrid Bergman was a free spirit with a sense of wanderlust who never became rooted in any one place whether artistically or geographically. As she stated in a late interview, “I don’t want any roots. I want to be free” when remarking on her ten-year sojourn in Hollywood after leaving Sweden where she never intended to remain. Eight years in Italy and then twenty years in Paris followed with her final years in spent in London, where she died. Claiming her independence following vilification in America once her affair with Roberto Rossellini became known, she states, “No one but I can decide how to live,” affirming that her private life is her own. Acting was her life. “If you took acting away from me, I would stop breathing.” Her diary entry records concern not working immediately after Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) with a four month delay before Casablanca (1942), starring, of course, Humphrey Bogart, who was not the typical Hollywood “glamor boy.” She describes frustration with this period of forced inactivity, despite being with her family, making her feel that “only half of me was alive.”

For Bergman, personal life and work were all part of a great adventure she felt necessary to participate in with 100% devotion. She owed much to female collaborators such as the friends to whom she wrote constant letters, colleagues such as dialogue coach Ruth Roberts, Irene Selznick, and Kay Brown. Her photographer/lover Robert Capa warned her about signing too many contracts that would make her a commodity and less of a human being, but other cinematic collaborators such as Alfred Hitchcock and Cary Grant proved positive lifelong influences. Used to dramatic performance, she appreciates Hitchcock’s sense of humor: “Every day with him is pure happiness. He brings out the best in me.” She finds Cary not stuck-up as she formerly believed, but considerate in every way. The documentary shows color home-movie footage of Hitchcock walking in a garden with possibly Alma reclined on a chair that was possibly taken by Bergman herself. As her daughter Isabella Rossellini states, Hitchcock taught Ingrid to “lighten up” in the same way as Jean Renoir wanted her mother to appear in Elena et les Hommes: “I wanted to film her in a comedy. I thought it was the right time.” Contrary to his usual practice of not allowing his wife to work with other directors during the time they were married, Roberto Rossellini allowed this one exception.

Yet despite contacting Rossellini to work with him after feeling bored with Hollywood limitations, the actress felt constrained due to her husband’s emphasis on improvisation and mostly working with non-actors. She had already made considerable achievements in Rossellini’s work, but despite their quality they did not receive the acclaim they deserved at the time – possibly due to the sexual nature of the blacklist concerning her personal life. After seeing Rome, Open City (1945) and Paisa (1946), she wanted to do something different and participate in another type of cinema that Hollywood could not provide. She strained at the leash artistically and fell victim to American Cold War sexual puritanism that regarded her as a “danger to American womanhood; even my voice on the radio was ‘dangerous.’” Following her desire to change both artistically and passionately she left Tinseltown and became vilified during her time with Rossellini. Along with Bergman’s insistence on controlling her personal life, this also applied to her art. “I must do the films I feel comfortable with.” Her return to Hollywood resulted in a second Best Actress Oscar for her role in Anastasia (Anatole Litvak, 1956; her first was Gaslight, 1944, and she later won Best Supporting for Sidney Lumet’s Murder on the Orient Express, 1974); her second statuette was as much due to her spirit of adventure as desire to challenge American sexual hypocrisy: “I’ve gone from saint to whore and back to saint in one lifetime.” One of the most nauseating segments in this documentary is Ed Sullivan cringing towards his audience asking them to poll him as to whether they wanted Bergman to appear on his show. The odious creep, who harassed John Garfield in his column five years earlier, mouths the platitude that she has had “7 and 1/2 years for repentance.” Whether Bergman thought the same is open to question.

Yet despite contacting Rossellini to work with him after feeling bored with Hollywood limitations, the actress felt constrained due to her husband’s emphasis on improvisation and mostly working with non-actors. She had already made considerable achievements in Rossellini’s work, but despite their quality they did not receive the acclaim they deserved at the time – possibly due to the sexual nature of the blacklist concerning her personal life. After seeing Rome, Open City (1945) and Paisa (1946), she wanted to do something different and participate in another type of cinema that Hollywood could not provide. She strained at the leash artistically and fell victim to American Cold War sexual puritanism that regarded her as a “danger to American womanhood; even my voice on the radio was ‘dangerous.’” Following her desire to change both artistically and passionately she left Tinseltown and became vilified during her time with Rossellini. Along with Bergman’s insistence on controlling her personal life, this also applied to her art. “I must do the films I feel comfortable with.” Her return to Hollywood resulted in a second Best Actress Oscar for her role in Anastasia (Anatole Litvak, 1956; her first was Gaslight, 1944, and she later won Best Supporting for Sidney Lumet’s Murder on the Orient Express, 1974); her second statuette was as much due to her spirit of adventure as desire to challenge American sexual hypocrisy: “I’ve gone from saint to whore and back to saint in one lifetime.” One of the most nauseating segments in this documentary is Ed Sullivan cringing towards his audience asking them to poll him as to whether they wanted Bergman to appear on his show. The odious creep, who harassed John Garfield in his column five years earlier, mouths the platitude that she has had “7 and 1/2 years for repentance.” Whether Bergman thought the same is open to question.

Adventure marked her character both in the realms of acting and personality. After appearing in some ten Swedish films in five years (several clips of which are shown, including one in which she stands out in an extra role), she made her only venture into Nazi Cinema – The Four Companions (1938), a clip of which appears. Whether she was naïve at the time merely wanting to work in a foreign country and speaking a strange language as she says, her letters to friends reveal political awakening. She writes that lots of people were scared in 1938 and that her colleagues on the set were worried of what was happening. When she begins a motor tour of Europe after filming ceased, her camera records ominous scenes of Hitler Youth, a shop with the sign “Jewish” on it, and color footage of marching SA. This camera footage reveals a rude awakening which she records honestly.

One later interesting sequence shows Sigourney Weaver, Isabella Rossellini, and Liv Ullmann accomplish Chekhov’s Three Sisters in their own right while seated together sharing reminiscences. Sigourney appeared as a young actress on stage with Ingrid in The Constant Wife directed by John Gielgud (1973); the former remembered Ingrid as down to earth, warm, and a joy to work with rather than a “showbiz monster.” Bergman was no monster but she could play one. I remember her performance as Hedda Gabler on BBC TV in 1962 opposite Michael Redgrave, Trevor Howard, and Ralph Richardson. It is a shame no clip was used since it showed her versatility as an actress. Liv recalls Ingrid’s difficulty playing a remorseful mother in a later scene in Ingmar Bergman’s Autumn Sonata (1978); Ingrid felt like slapping her screen daughter and walking away rather than having her character, Charlotte, apologize for sacrificing her to her career. An altercation followed between actress and director with Ingrid finally agreeing to play the role the director wanted rather than following her own personal feelings. Although Isabella later recognizes that her mother was not really happy with the traditional parental role, she values her as a friend and fun-loving person rather than someone getting the kids out of bed and to school. Ingrid’s sense of fun appears in most of the footage. One delightful color sequence shows an actor doing a tap dance on the set of Joan of Arc (1948) and Ingrid following suit in her Hollywood armor: “I belong to the make-up world of film and theater. I never want to leave it.”

One later interesting sequence shows Sigourney Weaver, Isabella Rossellini, and Liv Ullmann accomplish Chekhov’s Three Sisters in their own right while seated together sharing reminiscences. Sigourney appeared as a young actress on stage with Ingrid in The Constant Wife directed by John Gielgud (1973); the former remembered Ingrid as down to earth, warm, and a joy to work with rather than a “showbiz monster.” Bergman was no monster but she could play one. I remember her performance as Hedda Gabler on BBC TV in 1962 opposite Michael Redgrave, Trevor Howard, and Ralph Richardson. It is a shame no clip was used since it showed her versatility as an actress. Liv recalls Ingrid’s difficulty playing a remorseful mother in a later scene in Ingmar Bergman’s Autumn Sonata (1978); Ingrid felt like slapping her screen daughter and walking away rather than having her character, Charlotte, apologize for sacrificing her to her career. An altercation followed between actress and director with Ingrid finally agreeing to play the role the director wanted rather than following her own personal feelings. Although Isabella later recognizes that her mother was not really happy with the traditional parental role, she values her as a friend and fun-loving person rather than someone getting the kids out of bed and to school. Ingrid’s sense of fun appears in most of the footage. One delightful color sequence shows an actor doing a tap dance on the set of Joan of Arc (1948) and Ingrid following suit in her Hollywood armor: “I belong to the make-up world of film and theater. I never want to leave it.”

In a way, Ingrid “died with her boots on,” as Isabella recognized her mother working towards the very end, but she also valued her time with family and recorded it copiously. “She thought that everyone should be fulfilled by following their passion,” something that Isabella follows. Jeanine Basinger remarks on the home movie footage that “This is her family life,” seeing the camera as the link both to her lost parents and the family she had in her lifetime. This is an important recognition supplying a clue to the intention behind making this documentary. As Ingrid was frequently photographed by her late father, the camera symbolized the only roots she felt at home with, something that had nothing to do with geographical location and long-standing family ties, but the camera gave her an intuitive sense of the reality she sought. Like Mark Lewis in Peeping Tom (1960) Ingrid appears both behind and before the camera, but in a more affirmative manner, of course!

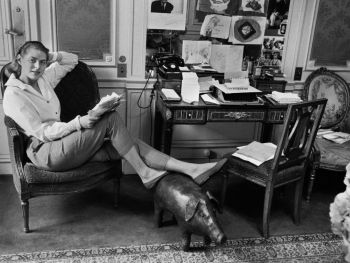

Paris, 1957.

Since Ingrid worked with Renoir and Rossellini, two directors celebrated by Andre Bazin, it seems logical to presume that Ingrid Bergman and director Bjorkman intuitively discerned certain key factors in that celebration of realism contained in Bazin’s essay “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” (1) The essay notes the camera’s role in continuing that mummy complex by providing a defense against the passage of time and artificially preserving the bodily appearance “to snatch it from the flow of time, to stow it away neatly, so to speak, in the hold of life” (9). This bereaved child sought to recapture moments when she was in front of her father’s camera lens by recording those special temporal movements that she knew were ephemeral and which she wished to cherish as “treasures.” Knowing her passion for constant change in artistic adventures, personal life, geographical re-locations, and her resistance of being confined to the ideologically static cages of marriage and family life, did not this free spirit seek to capture those transient moments of joy with her many children when they all experienced moments of happiness? Bergman may have recognized these moments as ephemeral, but they were loving interludes she sought to capture and preserve for all time knowing full well that real family happiness was but a “brief encounter” that the passage of time would abruptly remove. The camera was her instrument of preservation capturing those positive moments like “the charm of family albums,” embalming time, by “rescuing it simply from its proper corruption” (14). Contrasts between early images of her children and their middle-aged personae today reveal this process. It was one endemic within a post-war socio-historical conception of realism that was unique to that time and artistically explored by Renoir and Rossellini.

Ingrid Bergman herself contributed to that inherent sense of realism by her use of a camera lens where she explored her unique artistic abilities, which allowed her to be her own director by surpassing art in her own form of “creative power” (15), making cinema her own type of Bazanian “language” (16) by using it to express her own love for her family that was creative and genuine and far removed from dominant ideological conceptions. As Isabella Rossellini says, there will be no Mommie Dearest written by any of her children since she was “just too much fun to be with,” despite the limited time they all shared. Ingrid Bergman’s camera recorded those special moments that express personal feelings in her own appropriation of Bazanian realism in as much the same way as her diaries revealed her intimate thoughts to her female friends. Whether Bjorkman recognized this or not is irrelevant, for in a deeply artistic manner he has produced his own unique form of documentary utilizing those Bazanian traditions that contain key cinematic devices belonging to a particular era.

Tony Williams is Professor and Area Head of Film Studies in the Department of English, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. Co-editor with Esther C.M. Yau of Hong Kong Neo-Noir, forthcoming from University of Edinburgh Press, he has also recently signed a contract for his long-postponed study, James Jones: The Limits of Eternity.

Reference

Bazin, Andre (1967), “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” What is Cinema? Volume 1, Ed and Trans by Hugh Gray, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967, 9-16. The version from Film Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Summer, 1960) can be accessed here.