The 1950s are often seen as the time of Hollywood’s greatest splendour, yet the reality of the time was plummeting cinema attendance, which by 1953 came to be half of what it had been in 1946. In the face of radical social and economic changes, as well as the birth of television, Hollywood studios were confronted with a dooming prospect of complete extinction unless drastic steps were taken to attract audiences back to the movie theatres. In his book Film as Social Practice historian Graeme Turner identifies two ways in which the studios responded to the crisis: one was by “colonizing” television through producing films and programs for the small screen, the other was by attempting to lure the audience to the cinemas by the use of new technologies, such as Cinerama, Cinemascope and 3-D (Turner 1988: 14).

In the same work however, Turner identifies another vital characteristic of the cinema in the 1950s: “With the decline of the family film and the rise of the adult film in response to television’s capture of the family audience, mainstream cinema became more daring and explicit in its treatment of sex” (Turner 1988: 108).

The first sign of a radical shift in the way sexuality would be featured in main stream cinema had appeared as a result of another major occurrence, which significantly altered the cinema exhibition practices in the United States. In 1948 the Paramount Decree broke the production-distribution-exhibition chain, which had been the crucial driving force behind Hollywood’s success since the 1920s. This meant not only that the studios lost the monopoly on movie theatres, as Ellen Draper points out in an essay on movie censorship, it also meant that far fewer films were being produced in Hollywood (Draper 2000: 199).

Cinema exhibitors were now free to choose what films they wanted to show, and they started considering options outside of Hollywood. Italian films, such as Rome, Open City (directed by Roberto Rossellini, 1945), The Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948) and Bitter Rice (Giuseppe De Santis, 1949) caused a significant amount of controversy, while also proving successful at the box office. Although most of these foreign films were only shown in the art house movie theatres of large cities and university towns, the echo of the controversy was heard throughout the nation. While out of the three films mentioned only Bitter Rice can be seen as exploiting sexual imagery, foreign films in general came to represent bold and unapologetic content, which many saw as superior to the wholesome offerings of Hollywood.

Ellen Draper notes that “foreign films were controversial because they were aesthetically and morally foreign to many Americans who saw them” (Draper 2000: 198). The controversy surrounding the Italian cinematic exports would culminate with the 1950 release of The Miracle (directed by Roberto Rossellini), which prompted a long-standing debate on the artistic nature of movies and a court battle for the independence of cinematic content from the rules of censorship. While the final decision would not be reached until 1957, the seeds had been planted and the movie-going public begun expecting more mature themes.

In 1954, the January 27 edition of Motion Picture Daily declares that “sex is sexier and art is artier in those wonderful Italian movies.” The article continues to identify “six good reasons why America has taken Italian films to its bosom: Anna Magnani, Gina Lollobrigida, Sophia Loren, Silvana Mangano, Marina Vlady and Rossana Podesta,” suggesting unapologetically that sexualised images of women are the main reasons audiences attend the movies. While some right-wing groups, such as the National League of Decency, launched a crusade against movies such as The Miracle, many voiced their admiration for the frankness and artistic quality displayed in European films. Among these voices were influential Hollywood figures, such as directors Fred Zinnemann and Elia Kazan, who recognised the need for change and the public demand for more mature entertainment. Furthermore Hollywood could not fail to take note of the long queues which formed outside New York’s art houses to watch The Miracle, despite the Catholic leaders’ call for the film’s boycott. At this time of rapid box office decline sights like this were becoming rare and not something Hollywood producers could afford to ignore.

In 1954, the January 27 edition of Motion Picture Daily declares that “sex is sexier and art is artier in those wonderful Italian movies.” The article continues to identify “six good reasons why America has taken Italian films to its bosom: Anna Magnani, Gina Lollobrigida, Sophia Loren, Silvana Mangano, Marina Vlady and Rossana Podesta,” suggesting unapologetically that sexualised images of women are the main reasons audiences attend the movies. While some right-wing groups, such as the National League of Decency, launched a crusade against movies such as The Miracle, many voiced their admiration for the frankness and artistic quality displayed in European films. Among these voices were influential Hollywood figures, such as directors Fred Zinnemann and Elia Kazan, who recognised the need for change and the public demand for more mature entertainment. Furthermore Hollywood could not fail to take note of the long queues which formed outside New York’s art houses to watch The Miracle, despite the Catholic leaders’ call for the film’s boycott. At this time of rapid box office decline sights like this were becoming rare and not something Hollywood producers could afford to ignore.

In 1950 Columbia University’s Motion Picture Research Bureau, headed by Leo A. Handel, published the results of their findings on the cinema audience composition. As historian Robert Sklar notes in his essay “The Lost Audience,” the data published in the report “flew in the face of the accepted wisdom about movie audiences” (Sklar 1999: 83). Handel found that “male and female patrons attended at about equal rates,” while “younger people attended more often than older people” and “the more years a person spent in school the more frequently they see motion pictures” (Ibid.). These findings contradicted the well-established view of cinema as mainly family entertainment; it became clear that Hollywood had been failing to cater to some of its leading audience. Television could no longer be wholly blamed for the decline in movie attendance. As legendary producer Samuel Goldwyn remarked “why should people go out and pay money to see bad films when they can stay home and watch bad television for nothing.”

While television was certainly gaining popularity – in 1950 there were as many as 8 million television sets in the United States, by 1957 the number rose to 41 million (Bell-Metereau 2005: 107) – the majority of programmes were wholesome entertainment aimed at family audiences. Sex and adult themes were virtually absent from the small screen, and yet, as historian Richard Dyer notes, “1950s America had discovered sexuality as the key to the self, and the central aspect of adult life” (quoted from Turner 1988: 108). The reports of Alfred Kinsey (Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male in 1948 and Sexual Behaviour in the Human Female in 1953) showcased a sexually diverse society which stood in direct contrast with the conservative view of sexuality presented by Hollywood films and television. The Kinsey Reports found, for instance, that up to 50% of married men and 26% of married women had had some extramarital experience at some time during their married lives, while up to 37% of all males admitted to having experienced some form of homosexual relations. While both adultery and homosexuality might have been a significant part of the fabric of American society, in Hollywood cinema both subjects were taboo. In accordance with the rules of the Production Code, showing any form of “sexual perversions” (which encompassed homosexuality) and adulterous sexual activity of any kind were strictly forbidden, unless suggested as means of moral caution and punished at the end of the story (Pennington 2007: 6). The rules of the Code, which had been written in 1934, remained virtually unchanged, and by the early 1950s seemed more than a little dated and out of sync with the moral standards of post-war society.

Starting in 1951, the year of the release of Elia Kazan’s A Streetcar Named Desire, we can observe a significant rise in the production of movies which dare to explore themes expressly forbidden by the Production Code. While the battle with the censors continued throughout the decade, there is no doubt that the filmmakers, studio publicity departments and motion picture exhibitors found ways of effectively bypassing the system. The early successes of films such as Streetcar and later From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953), as well the rapid rise to stardom of such actors as Marilyn Monroe and Marlon Brando, proved that sex and sexual themes sold well and the struggle against censorship was well worth the fight.

In order to legitimise the claims of an intellectually superior content many filmmakers reached for critically acclaimed novels and stage plays in order to deal with controversial issues. A Streetcar Named Desire, based on a play by Tennessee Williams, can be seen as one of the first American movies which benefited from the shifting attitudes towards sexuality and the influence European films had on the change in audiences’ reception of mature themes. As Jody Pennington notes “European imports during the 1950s were especially influential in making adultery an acceptable theme” (Pennington 2007: 153). However Kazan’s adaptation of Streetcar proved controversial on more than one level, tackling such taboo issues as homosexuality, mental illness and rape. An early memo from Joseph Breen, the chief administrator of the Production Code, sent to Jack Warner reflects just how delicate the matter of filming Streetcar was:

“You will bear in mind that the provisions of the Production Code are quite patently set down in the knowledge that motion pictures, unlike stage plays, appeal to mass audiences; to the mature and the immature […]. Material which may be perfectly valid for dramatization on the stage may be questionable, or even completely unacceptable in a motion picture.” (Staggs 2005: 227)

Despite the objections from Breen’s office, as well as a condemnation threat from the National Legion of Decency, Elia Kazan managed to keep most of the original content intact. While the homosexuality of Blanche’s husband, as well as her sordid past, were toned down and reduced to being more a suggestion than a stated fact, there could be no doubt that A Streetcar Named Desire dealt with the dark areas of human sexuality quite unlike any motion picture before it.

The fact that the public embraced the film, making it one of the top five box office hits of 1951, dramatically altered the way adult-themed movies were marketed and exhibited. The promotional materials for Streetcar approached its sexual content with caution. Sam Staggs notes that “the studio must have felt justifiably jumpy in view of Streetcar’s general heavy-skies subject matter, its absence of guns, jokes, sentiment and happy ending, as well as the lingering fear that the disgruntled might foment some new controversy” (Staggs 2005: 251).

Despite the cuts in the depiction of homosexuality and other issues deemed too controversial by Breen, the official promotional poster promised “all the fire” of the original play, the Broadway success of which served as an ideal form of free publicity. Yet despite the play’s reputation, or perhaps because of it, Radio City Music Hall withdrew their offer of hosting the movie’s premiere, fearing the wrath of the Legion of Decency. The film eventually premiered in Atlantic City, before a gala opening in Hollywood.

Considering the power the National Legion of Decency was believed to hold over cinemagoers, it is hardly surprising that exhibitors approached Streetcar with caution. Condemnation by the Legion or other religious organisations could mean not only the boycott of a film but also a threat of revoking exhibition licences. The fate of Streetcar rested largely on the star power of Vivien Leigh, who, at the time of the film’s release, was the only established star in the cast. The presence of a respected, Academy Award winning actress in the movie not only guaranteed an audience but also added to the film’s prestige. The critical reception of the film by the secular press was overwhelmingly positive, with The New York Times stating that, “comments cannot do justice to the substance and the artistry of this film. You must see it to appreciate it. And that we strongly urge you to do” (Crowther 1951).

Considering the power the National Legion of Decency was believed to hold over cinemagoers, it is hardly surprising that exhibitors approached Streetcar with caution. Condemnation by the Legion or other religious organisations could mean not only the boycott of a film but also a threat of revoking exhibition licences. The fate of Streetcar rested largely on the star power of Vivien Leigh, who, at the time of the film’s release, was the only established star in the cast. The presence of a respected, Academy Award winning actress in the movie not only guaranteed an audience but also added to the film’s prestige. The critical reception of the film by the secular press was overwhelmingly positive, with The New York Times stating that, “comments cannot do justice to the substance and the artistry of this film. You must see it to appreciate it. And that we strongly urge you to do” (Crowther 1951).

While the Legion still protested against the film’s “projection of an atmosphere of lust and carnal desire,” (Black 1997: 94), audiences flocked to the movie theatres to see it, and by the end of its run A Streetcar Named Desire made over 4 million dollars. The critical success of Kazan’s film was also confirmed at the Academy Awards, where Streetcar won four awards, including one for Vivien Leigh as best actress.

Other adaptations of controversial literary works followed, and encouraged by the success of A Streetcar Named Desire, the studios no longer feared publicising their sexual content. The 1953 adaptation of James Jones’s novel From Here to Eternity is perhaps the most poignant example of such exploitation. In her essay “Movies and Our Secret Lives” film historian Rebecca Bell-Metereau argues that “while the war theme may have drawn male viewers who wanted to relive the excitement of combat, publicity posters of Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr embracing in the surf on the beach clearly appealed to a different set of desires” (Bell-Metereau 2005: 101).

The graphic representation of sheer sexual pleasure as the most prominently publicised still for a mainstream movie shows just how rapidly the embracing of a new, more liberal attitude progressed. It is also worth noting that the relationship between Milton Warden (Burt Lancaster) and Karen Holmes (Deborah Kerr) is an adulterous one, and yet the scene of their passionate encounter is employed as the key moment in the film.

While it was certainly more difficult to bypass the rules of the Production Code in the actual narrative story, the visual side of the promotional materials seemed to be free of such restrictions. Both producers and exhibitors discovered that a well-publicised film, which promised a daring, sexually explicit story had a far greater chance at succeeding at the box office. Hence, for instance, when promoting films such as From Here to Eternity it was vital for the promotional posters to include such taglines as, “The boldest book of our time… Honestly, fearlessly on the screen!” This, combined with a tantalising image of Lancaster and Kerr on the beach, created a visual message which appealed to the scopophilic instincts of the public. Rebecca Bell-Metereau goes as far as stating that “the beach scene probably constituted a chief reason for the film’s overwhelming popularity” (Bell-Metereau 2005: 103). The film eventually went on to become one of ten most profitable pictures of the 1950s, winning eight Academy Awards, and proving once and for all that a story with sexually controversial elements was what the public wanted and what the critics appreciated.

While it was certainly more difficult to bypass the rules of the Production Code in the actual narrative story, the visual side of the promotional materials seemed to be free of such restrictions. Both producers and exhibitors discovered that a well-publicised film, which promised a daring, sexually explicit story had a far greater chance at succeeding at the box office. Hence, for instance, when promoting films such as From Here to Eternity it was vital for the promotional posters to include such taglines as, “The boldest book of our time… Honestly, fearlessly on the screen!” This, combined with a tantalising image of Lancaster and Kerr on the beach, created a visual message which appealed to the scopophilic instincts of the public. Rebecca Bell-Metereau goes as far as stating that “the beach scene probably constituted a chief reason for the film’s overwhelming popularity” (Bell-Metereau 2005: 103). The film eventually went on to become one of ten most profitable pictures of the 1950s, winning eight Academy Awards, and proving once and for all that a story with sexually controversial elements was what the public wanted and what the critics appreciated.

Other daring adaptations of literary works continued to appear throughout the 1950s, including films like Peyton Place (Mark Robson, 1957), which dealt with the risky subject of teenage sexuality. The works of Tennessee Williams proved particularly successful in carrying sexual content and the publicity for these films is especially worth analysing. Baby Doll (Elia Kazan, 1956), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (Richard Brooks, 1958) and Suddenly, Last Summer (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1959) all benefited from the controversy which surrounded them, as well as from the carefully planned publicity campaigns especially designed for each movie. Elizabeth Taylor, who starred in the latter two, was one of the most popular actresses of the era, not least because of her turbulent private life. During the shooting of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof Taylor’s husband, producer Mike Todd, died in a plane crash. Following his death Taylor begun a much talked-about affair with Eddie Fisher, who was then married to Debbie Reynolds. The scandal which surrounded the affair and their subsequent marriage was used by MGM as a promotional tool. While in the 1940s an adulterous affair meant serious damage to an actor’s career (Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini being an obvious example), the public of the 1950s was far more forgiving. Taylor’s overtly sexual image is highlighted in promotional posters for both Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Suddenly, Last Summer, both released at the height of the scandal.

Just like in the case of A Streetcar Named Desire, the poster for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof promises “every steamy moment of the Tennessee Williams’ Pulitzer Prize winning play,” despite the fact that some of the most controversial lines, especially ones which alluded to Brick’s homosexuality, were eliminated from the screenplay. Similarly, the ending was changed to suit the rules of the Production Code and to avoid a C-rating from the Legion of Decency.

The image of Taylor used on the poster never actually appears in the movie. She is symbolically placed on the bed to highlight her sexual power and to emphasise the provocative themes of the film. In the poster for Suddenly, Last Summer Taylor’s sexual image is used once again, this time she is wearing a one-piece bathing suit, which, as she describes it in the film, “makes her appear nude.” It is interesting to notice that her two co-stars, Katharine Hepburn and Montgomery Clift, while equally famous and just as vital to the film’s narrative, are featured in a considerably less prominent fashion. There is no doubt that Taylor’s sexuality is the main point of attraction in both films, and as such her image is used to attract audiences.

The image of Taylor used on the poster never actually appears in the movie. She is symbolically placed on the bed to highlight her sexual power and to emphasise the provocative themes of the film. In the poster for Suddenly, Last Summer Taylor’s sexual image is used once again, this time she is wearing a one-piece bathing suit, which, as she describes it in the film, “makes her appear nude.” It is interesting to notice that her two co-stars, Katharine Hepburn and Montgomery Clift, while equally famous and just as vital to the film’s narrative, are featured in a considerably less prominent fashion. There is no doubt that Taylor’s sexuality is the main point of attraction in both films, and as such her image is used to attract audiences.

Taylor was not the only star whose sexualised image was employed to attract cinema audiences. Highly sexual screen personas of stars such as Marilyn Monroe and Ava Gardner guaranteed box office success, while at the same time constituting a trap for these gifted actresses, who found themselves unable to play parts outside of the tested formula. Gardner was mainly being cast as the earthy temptress in such profitable movies as Mogambo (John Ford, 1953) and The Barefoot Contessa (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1954). Original publicity posters for both movies showcase a highly erotic image of the actress, projecting scenes which in both cases are not part of the film’s actual narrative. While in the credits of The Barefoot Contessa Humphrey Bogart receives top billing, the poster only includes a vague and colourless drawing of the actor’s face, while Gardner, erotically embraced by a man and wearing a tight dress, occupies the central space. Similarly, in the poster for Mogambo it is the image of Gardner and Clark Gable in a passionate embrace which becomes the main visual element, together with a tagline, “The Battle of the Sexes.”

Taylor was not the only star whose sexualised image was employed to attract cinema audiences. Highly sexual screen personas of stars such as Marilyn Monroe and Ava Gardner guaranteed box office success, while at the same time constituting a trap for these gifted actresses, who found themselves unable to play parts outside of the tested formula. Gardner was mainly being cast as the earthy temptress in such profitable movies as Mogambo (John Ford, 1953) and The Barefoot Contessa (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1954). Original publicity posters for both movies showcase a highly erotic image of the actress, projecting scenes which in both cases are not part of the film’s actual narrative. While in the credits of The Barefoot Contessa Humphrey Bogart receives top billing, the poster only includes a vague and colourless drawing of the actor’s face, while Gardner, erotically embraced by a man and wearing a tight dress, occupies the central space. Similarly, in the poster for Mogambo it is the image of Gardner and Clark Gable in a passionate embrace which becomes the main visual element, together with a tagline, “The Battle of the Sexes.”

Studio publicity campaigns extended beyond posters, and included the use of movie magazines, theatrical trailers and television appearances. Theatrical trailers, like posters, were designed to highlight the provocative nature of the film, choosing the most tantalising scenes and heightening the audience’s anticipation with the use of voice-over commentary as well as textual adornments. These elements offered an extra-narrative insight and promoted the risky content. Many of the original trailers exploit the sexual imagery while altering the actual narrative value of the film they promote, often promising more than was possible to deliver under the censorship rules. The trailers aimed to sell more than just the film; they were a way of promoting the studio, its stars and the technical advancements used (for example the sexual personas of stars like Monroe and Gardner, often in connection with technical innovations like Cinemascope and Technicolor).

Television also played its part in promoting cinema’s titillating qualities. Shows such as What’s My Line regularly invited movie actors to appear and promote their upcoming films. These appearances were often accompanied by comic routines which were designed to highlight the stars’ sexual power and promise more sexual content upon viewing of the promoted film. Female stars usually entered the stage accompanied by the sound of wolf-whistling from the audience, and were often subjected to highly suggestive remarks from the hosts. This symbiotic relationship between television and cinema showcases just how important the new medium became. By 1955 most of the top Hollywood stars, such as Ava Gardner, Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor, had made their television debuts on such shows as What’s My Line?, This Is Your Life and The Jack Benny Show. The appearance of these sex symbols on the family-friendly screens teased the audience with the idea that, while on television all must remain in the realm of a suggestive joke, the cinema screen and the films these stars appear in offer a more explicit insight into their sexually charged realities.

Central to this strategy were movie stars with exclusively sexual personas, such as Marilyn Monroe. Monroe represented pure sexuality, and virtually all the films in which she had a starring role were promoted around her erotic image. Starting in 1953, when she appeared in Niagara (Henry Hathaway), Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks) and How to Marry a Millionaire (Jean Negulesco), Monroe was regularly voted top female box office star by the American film distributors (Dyer 2004: 25). Monroe’s image perfectly suited the notions surrounding sexuality in this period. In the majority of her early films she portrays a good-hearted gold-digger (Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, How to Marry Millionaire) whose ultimate goal is marriage, or a fantasy woman who, while highly sexual, is unthreatening to the moral structure of the nuclear family (The Seven Year Itch). Unlike in the case of the femme fatales of the 1940s, Monroe’s sexuality is not lethal or emasculating, but rather designed to flatter the male ego. Monroe’s 1954 film The Seven Year Itch (Billy Wilder) is possibly the best example of how sexuality and star image were used to attract audiences in the 1950s, both in terms of the film’s narrative structure and the publicity campaign used to promote it.

The film, based on a hit Broadway play by George Axelrod, constantly plays with the idea of sexual fantasy, with Monroe as the embodiment of the ultimate male “dream come true.” Fantasy and the privatisation of erotic desires was one of the key characteristics of 1950s male sexuality, with Kinsey’s studies finding that 84% of males interviewed “indicated that they were sometimes aroused by thinking of sexual activities with females.” In 1953 the first issue of Playboy magazine appeared on the market, signifying a major shift in the way male fantasies were commercialised. Significantly, Monroe’s image appeared on the first cover of Playboy, while nude photographs from a calendar she had posed for prior to becoming a star were used inside the magazine. While the fact that America’s number one movie star had posed nude caused a major scandal, the popularity of neither Monroe nor Playboy were affected, which in itself is an unequivocal testament to the change of moral attitudes which was taking place. Time magazine reported, in August 1952, that “Marilyn believes in doing what comes naturally” (quoted from Dyer 2004: 29), a line which highlights the innocence of Monroe’s sexuality and, indeed, the belief in the natural and quilt-free quality of sex itself.

Monroe’s character in The Seven Year Itch also poses for erotic photographs, which is only one of the many parallels between the actress and her on-screen persona. Significantly, her character also appears on television, where she advertises toothpaste. The film’s comic depiction of the consumerist culture mocks the sexualisation of advertisement, the very same technique which is used to promote the film itself. Richard Sherman (Tom Ewell) portrays a publishing advertisement worker, who, in an early scene in the film, suggests the cleavage lines of the female drawings on the cover of Little Women be lowered to ensure better sales.

Monroe’s character in The Seven Year Itch also poses for erotic photographs, which is only one of the many parallels between the actress and her on-screen persona. Significantly, her character also appears on television, where she advertises toothpaste. The film’s comic depiction of the consumerist culture mocks the sexualisation of advertisement, the very same technique which is used to promote the film itself. Richard Sherman (Tom Ewell) portrays a publishing advertisement worker, who, in an early scene in the film, suggests the cleavage lines of the female drawings on the cover of Little Women be lowered to ensure better sales.

In another scene, when asked about the mysterious blonde in his kitchen, Sherman replies, ‘Wouldn’t you like to know, maybe it’s Marilyn Monroe!’ The line between real life and cinematic fiction is deliberately blurred to give the audience the illusion of having privileged access to the erotic dimension occupied by Monroe. With the narrative structure built to be told from Ewell’s point of view, Monroe becomes the object of both his, as well as the audiences’ scopophilic gaze. Laura Mulvey describes this process in her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”: “traditionally the woman displayed has functioned on two levels: as erotic object for the characters within the screen story, and as erotic object for the spectator within the auditorium” (Mulvey 1975). It is vital, however, to once more take Mulvey’s argument out of the movie theatre and into the streets, where, particularly in the case of stars such as Monroe and films such as The Seven Year Itch, the initial point of visual connection between spectators and sexualised images of stars occurred. The Seven Year Itch, arguably more than any other movie in history, is mainly associated with a single publicity still. The iconic image of Marilyn Monroe standing over a subway ventilator which blows up her skirt can be seen as a pivotal moment in the discourse on sexuality as a means of promoting cinema in the 1950s. No other single image projects such a tantalising and exhilarating moment of sheer enjoyment of one’s sexuality, while at the same time signifying cinema’s ruthless exploitation of a star’s body and sexual image.

During the publicity campaign for the film a sixty foot poster of Monroe was put up in New York’s Times Square. Surviving newsreel footage showcases the process and the reactions of the people who gather to observe the spectacle. While the reactions of the male members of the public are highly favourable, with remarks such as “I think it’s wonderful. Wonderful, wonderful, wonderful” and “Very nice. Some girl!”, the female comments are less enthusiastic: “I think it’s very nice but I’d rather it was me” and “What Marilyn Monroe has, millions of other girls have and choose not to show.”[1]

During the publicity campaign for the film a sixty foot poster of Monroe was put up in New York’s Times Square. Surviving newsreel footage showcases the process and the reactions of the people who gather to observe the spectacle. While the reactions of the male members of the public are highly favourable, with remarks such as “I think it’s wonderful. Wonderful, wonderful, wonderful” and “Very nice. Some girl!”, the female comments are less enthusiastic: “I think it’s very nice but I’d rather it was me” and “What Marilyn Monroe has, millions of other girls have and choose not to show.”[1]

Richard Dyer argues that Monroe became a polarising figure within the discourse on the representation of women from the very beginning, representing both sexual freedom and the desire to break free from the constraints of the male-driven studio system, as well as the very objectification of women as sexual objects. Indeed 20th Century Fox had used Monroe’s sexual image as a bankable commodity from the very beginning, when she was first signed to a contract in 1951. While still playing small parts in insignificant films Monroe appeared in countless publicity stills, usually wearing a bathing suit or a tight evening dress. As her popularity grew and the studio begun realising her potential, Monroe’s image became more refined, transforming her from the all-American girl next door to the sex goddess of Niagara and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

After the box office success of both films, Fox realised that Monroe’s sexual persona could also be used to promote Hollywood’s latest technical inventions. This is particularly interesting when considering that technical innovations, such as Cinemascope, were themselves designed to attract audiences, and yet the novelty of the process itself was not attractive enough without the use of sexualised images of stars. In the promotional poster for How to Marry a Millionaire we see Monroe placed in the central position, quite literally luring the audience to see the film, while the Cinemascope logo appears prominently above her and her co-stars.

How to Marry a Millionaire was a great success, however it is far more likely that it was due to Monroe’s popularity rather than the use of Cinemascope. Graeme Turner writes in his book that “paradoxically, the greater success Cinemascope had in carrying a narrative, the less apparent was the technological invention itself” (Turner 1988: 15), and while the studio could not count on Cinemascope alone to bring in the audience, the power of Monroe’s sexual hold on her public was a far more reliable strategy.

While in the decades which followed her death Marilyn Monroe came to symbolise much more than just a sexual object designed to attract cinema audiences, during the 1950s her popularity and ability to sell tickets was the studio’s main focus. No doubt part of Monroe’s allure was the fact that she herself was at odds with her own image as a sex symbol, constantly trying to improve herself and showcase her abilities as a serious actress. When in 1955 she left Hollywood to study at New York’s Actor’s Studio, Fox frantically tried to fill the box office gap she created by promoting other actresses which were moulded to imitate Monroe (for example Sheree North). Other studios also tried to capitalise on Monroe’s success, with actresses such as Jayne Mansfield (Paramount), Mamie Van Doren (Universal), and Kim Novak (Columbia) all promoted as possible successors. In 1956 for instance, Mansfield was cast opposite Tom Ewell, Monroe’s co-star in The Seven Year Itch, in the comedy The Girl Can’t Help It (Frank Tashlin), which emphasised her overtly-sexual persona in a manner closely resembling Monroe.

While films like The Girl Can’t Help It were popular with audiences, none of the other actresses in the blonde bombshell category managed to achieve the level of success comparable to Monroe’s. Richard Dyer argues that, although her star persona was certainly carefully crafted by the studio, her sexuality was natural and innocent, and therefore far more effective: “Monroe did appear natural in her sexiness and with an originality that necessarily had an impact among the stream of conventionally pretty starlets and pin-ups that the studio continually produced” (Dyer 2004: 33).

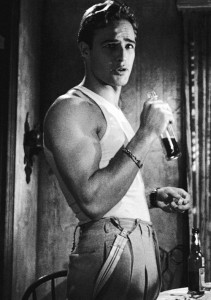

While I have mainly focused on the way female sexuality was used to attract audiences, it is worth mentioning that publicising sexual content in the 1950s was not exclusively limited to the exploitation of the female body. Starting with Marlon Brando’s appearance in A Streetcar Named Desire, the cinematic image of the male body had undergone a significant transformation of its own. Brando constitutes the film’s main object of sexual desire and, in the reversal of Laura Mulvey’s argument of women as objects of male gaze, he becomes the object of gaze for both the female characters within the film and the spectator. In her essay “Movies and the New Faces of Masculinity,” Kristen Hatch notes that Stanley (Brando) “is repeatedly filmed in such a way as to highlight his muscular beauty” (Hatch 2005: 58). This is achieved both by camera work and the revolutionary concept of using undershirts and vests as Stanley’s primary costumes in the film. Brando’s sexual presence shifts the balance of the narrative structure, taking some of the attention away from the figure of Blanche and usurping a degree of the spectator’s support, which is dictated by a scopophilic instinct.

While I have mainly focused on the way female sexuality was used to attract audiences, it is worth mentioning that publicising sexual content in the 1950s was not exclusively limited to the exploitation of the female body. Starting with Marlon Brando’s appearance in A Streetcar Named Desire, the cinematic image of the male body had undergone a significant transformation of its own. Brando constitutes the film’s main object of sexual desire and, in the reversal of Laura Mulvey’s argument of women as objects of male gaze, he becomes the object of gaze for both the female characters within the film and the spectator. In her essay “Movies and the New Faces of Masculinity,” Kristen Hatch notes that Stanley (Brando) “is repeatedly filmed in such a way as to highlight his muscular beauty” (Hatch 2005: 58). This is achieved both by camera work and the revolutionary concept of using undershirts and vests as Stanley’s primary costumes in the film. Brando’s sexual presence shifts the balance of the narrative structure, taking some of the attention away from the figure of Blanche and usurping a degree of the spectator’s support, which is dictated by a scopophilic instinct.

Throughout the 1950s other studios capitalised on this new-found appeal of male sexual aesthetics, by advertising films such as Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955), using a highly eroticised image of bare-chested William Holden, and From Here to Eternity, where Burt Lancaster’s athletic physique becomes the most prominent visual element.

It is worth noting that the male sex symbols of the era, like Brando and Holden, represent the strong, masculine and athletic image of an all-American man, designed to re-establish male dominance undermined by the trauma of the Second World War.

During the 1960s the Production Code gradually became less and less influential, until it was replaced by a rating system in 1968. With the declining power of the Code, main stream movies became more daring in their exploration of adult themes, while sexploitation and porn films also became more widely available. However the changes which took place during the 1960s ought to be seen as a direct continuation of an ongoing process of using sexual images to attract cinema audiences, which was already firmly in place during the 1950s.

Anthony Uzarowski is a Film Studies MA graduate from University College London, currently working on his first book, an illustrated biography of Ava Gardner, due to be published by Running Press. He spent a year in Rome, studying film and researching the Cinecitta Film Studios. His main research interests are classic Hollywood, star studies and representation of women in film, as well as Italian and Polish national cinemas.

References

Bell-Metereau, Rebecca (2005), “Movies and Our Secret Lives,” in Murray Pomerance (ed.), American Cinema of the 1950s: Themes and Variations, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, pp. 89-110.

Black, Gregory D. (1997), The Catholic Crusade Against Movies, 1940-1975, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Crowther, Bosley (1951), “Movie Review: A Streetcar Named Desire”, The New York Times, 20 September 1951. Accessed 1 April 2016.

Draper, Ellen (2000), “‘Controversy has Probably Forever destroyed the Context’: The Miracle and Movie Censorship in America in the 1950s,” in Matthew Bernstein (ed.), Controlling Hollywood: Censorship and Regulation in the Studio Era, London: Athlone Press, pp. 186-205.

Dyer, Richard (2004), Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society, London: Routledge.

Hatch, Kristen (2005), “1951: Movies and the New Faces of Masculinity,” in Murray Pomerance (ed.), American Cinema of the 1950s: Themes and Variations, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, pp. 43-64.

Merck, Mandy (ed.), The Sexual Subject: A Screen Reader in Sexuality, London: Routledge.

Mulvey, Laura (1975), “Visual pleasure and narrative cinema”, Screen, vol. 16, issue 3, pp. 6-18.

Pennington, Jody W. (2007), The History of Sex in American Film, New York: Praeger Press.

Rogers, Ariel (2012), “Smothered in Baked Alaska: The Anxious Appeal of Widescreen Cinema,” Cinema Journal, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 74-96.

Schrecker, Ellen (1994), The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents, New York: Bedford Books.

Sklar, Robert (1999), “‘The Lost Audience’: 1950s Spectatorship and Historical Reception Studies,” in Melvyn Stokes and Richard Maltby (eds.), Identifying Hollywood’s Audiences: Cultural Identity and the Movies, London: BFI, pp. 81-92.

Spoto, Donald (1993), Marilyn Monroe: The Biography, London: Chatto & Windus.

Staggs, Sam (2005), When Blanche Met Brando: The Scandalous Story of A Streetcar Named Desire, New York: St Martin’s Griffin.

Stokes, Melvyn and Richard Maltby (eds.) (1999), Identifying Hollywood’s Audiences: Cultural Identity and the Movies, London: BFI.

Turner, Graeme (1988), Film as Social Practice, New York: Routledge.

Wright, Ellen (undated), “‘Glamorous Bait for an Amorous Killer’: How post-war audiences were Lured by Lucille and the working-girl investigator”, Frames Cinema Journal. Accessed 1 April 2016.

[1] This footage can be seen in the documentaries Marilyn vs. Marilyn (2002) and Marilyn in Manhattan (1998), both available on Youtube at the time of writing (4 April 2016).