By Elias Savada.

Unless you’re orbiting the art universe, particularly in the vicinity of its comically subversive galaxy, you’ve probably never heard of Robert Cenedella, who is both a bastard (in the biblical sense) and an artist (in a mostly mythological/fantastical off-the beaten-path way) in Art Bastard, a sprightly designed look at this fiercely independent troublemaker, who has been on the sidelines of the New York City art scene for decades.

The film comes courtesy of first-time feature writer-director Victor Kanefsky (father of Rolfe, an avid writer-director of over two dozen horror-thriller films). Kanefsky père has an interesting résumé, mostly as a film editor dating back to 1969’s Tiny Lund: Hard Charger, an obscure documentary about an independent stock car racer who would die while competing in the Talledega 500 two years later. After founding Valkhn Film & Video, a post-production facility, in 1972, he edited such indie docs as Our Latin Thing (1972) and Style Wars (1983), while also cutting such cult classics as Troma Entertainment’s scripted-in-one-day Bloodsucking Freaks (1976) and Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess (1973), featuring Duane Jones, star of Night of the Living Dead. G&H was so gutted by its distributor in a re-release, that Gunn, Kanefsky, and producer Chiz Schultz demanded their names be removed from the credits. (In 2014, Spike Lee released his reworking of the film, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus.) Integrity stands tall in his life. Kanefsky also taught filmmaking at New York University.

So, now, 60 years into show business and 85 years into life, Kanefsky gets his 85-minutes of fame up on the big screen. He makes a very nice debut, as does editor Jim MacDonald in his rookie credit as primary editor. Art Bastard is a nicely paced, well cut film, particularly when Cenedella’s artwork is the focus of Douglas Meltzer’s camera. Yes, the film is a well done highlights biography, despite a little too much footage watching its rumpled subject walk the Big Apple streets. There are some grandly edited sequences that captured my attention, such as…

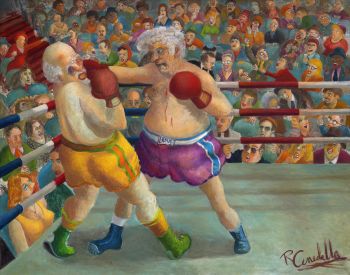

Early in the film, as Cenedella is shuffling about the New York City subways, one of his many colorful works (“Fun City Express”) is intercut with the action. The jiggle of the painted train and riders is captured in a cinema verité fashion, as if the painting’s subjects were being followed by a hand-held camera. It’s a quietly creative technique which reappears in a boxing ring scene (using Cenedella’s 1977 painting “Father’s Day”), now with quick cuts between the two caricatures (representing both his fathers) as the crowd on the soundtrack roars as punches hit home. The artist comments, “This is definitely a painting where I was doing therapy on the canvas.” The finely-tuned intensity of all the cinematic (sound and picture) elements raises the level of appreciation of the film immeasurably.

Embellished with a riverside chat between Cenedella and his sister, comments by his wife, brief observations by his son, and remarks by critic Marvin Kitman, Richard Armstrong (director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), and a dozen others (dealers, agents, investment managers, restauranteurs, writers), plus interesting footage (a mix of stock and current) of NYC museums, etc., the story that is Cenedella’s life takes shape. His rebellious history and opinions are laid bare, mostly in good fun, but not without its sad moments, especially when ruminating on the death of his tutor George Grosz in 1959.

His non-biological father was a radio writer in the 1930s and 1940s, a member of the Radio Writers Guild, and blacklisted by Joe McCarthy and his congressional idiots for refusing to divulge if he was a Communist. A subject for another film. Following in his presumed father’s footsteps, Cenedella refused to sign a loyalty oath in high school. He was expelled.

His non-biological father was a radio writer in the 1930s and 1940s, a member of the Radio Writers Guild, and blacklisted by Joe McCarthy and his congressional idiots for refusing to divulge if he was a Communist. A subject for another film. Following in his presumed father’s footsteps, Cenedella refused to sign a loyalty oath in high school. He was expelled.

The focus on the film is how life shaped this particular artist and the assortment of politically, socially, and/or culturally inspired events that populate his art. His love of music (looking out to see the audience from an orchestra’s POV, or a Hitlerized conductor leading his ensemble and being watched by his spectators, all with similar moustaches), and of sport (the comical placement of a hockey stick up the derriere of a New York Ranger, or a player speared atop one of the goals – in front of a sideboard ad for the NRA – during a melee with the Boston Bruins, with the appropriate organ cues on the soundtrack). The film enjoys emphasizing such gallows humor sequences. They’re so grotesquely absurd that you want to see more. You must see more of this oh-so-much-lighter side of Hieronymus Bosch by way of those funny, ironic New Yorker magazine cartoons.

When Cenedella begins a commentary on the marketing of art, particularly with the arrival of Pop Art, the film recalls his decision to fight back against the use of art as a sales tool by creating a one-off gallery show bordering on the absurd called “Yes Art.” Poking fun at the Warhol party crowd, he parodied the Brillo box, the Love painting by Robert Indiana, and other corruptions of the commercialized medium. He was so upset with what was happening that he stopped painting for ten years, especially after the joke seemed to be acceptable to many.

What did he do then? He got a job in advertising! (I wonder if he knew Don Draper?) Then he went into the poster business, where the CIA questioned him about presidentially-themed dart boards. Thankfully, he returned to his first calling, although some of his work has proven irksome to the I-don’t-get-the-joke crowd. At a showing of his major show in the lobby of the Saatchi & Saatchi building in 1988, “The Presence of Man.” a painting of a crucified Santa Claus, got axed by his not-very-jolly underwriters. This was not the holiday spirit they wanted to support during the Christmas shopping season.

Kanefsky follows his subject with a hand-held camera as he talks about the grim what’s in – what’s out lottery of the contemporary art scene. It does seem the economics of any particular art piece is what is driving the conservative art business.

Art Bastard is a brisk, vibrant portrait of a young, determined artist as an old man. I love a good skewering, and the serious-funny side of life that is celebrated in Cenedella’s oeuvre gets an engaging look-see in this excellent film.

Elias Savada is a movie copyright researcher, critic, craft beer geek, and avid genealogist based in Bethesda, Maryland. He helps program the Spooky Movie International Movie Film Festival, and previously reviewed for Film Threat and Nitrate Online. He is an executive producer of the new horror film German Angst and co-author, with David J. Skal, of Dark Carnival: the Secret World of Tod Browning.