Godard called his masterwork Weekend (1967) “a film lost in the cosmos – a film found on the scrapheap” in that movie’s intertitles, but at least it opened in a theater in New York, played there for months, and then made the rounds on the university and art house circuit in the era before video on demand all but obliterated that discerning marketplace, and remains a film that most cineastes know – at least the ones who deserve the title. But with the demise of this theatrical circuit, newer films play at festivals only, and then are dumped on pay per view, where no one even knows they exist, and then they vanish. That’s the fate of independent film today.

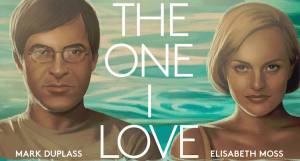

The One I Love (2014) is yet another film that’s been completely overlooked in the headlong rush to the multiplex, yet it’s a stunning directorial debut by Charlie McDowell, from a script by Jonathan Lader, and produced by the Duplass Brothers, Mark and Jay (Charlie McDowell, incidentally, is actor Malcolm McDowell’s son with Mary Steenburgen). Mark Duplass does double duty – an apt turn of phrase, as you will see – starring in the film, in addition to his co-producer role, as harried husband Ethan, who is first seen in a therapy session, both angry and repentant after having cheated on his wife Sophie (Elizabeth Moss, best known for her work on the TV series Mad Men). More on that later.

Yet, for all the force and power that The One I Love possesses, it might as well not have been made at all, so quickly did it disappear. As Wikipedia notes, after a well received screening at the Sundance Film festival on January 21, 2014, “The One I Love opened in a limited release [on August 22, 2014] in the United States in 8 theaters and grossed $48,059 with an average of $6,007 per theater and ranking #42 at the box office. The film’s widest release was 82 theaters and it ended up earning $513,447 domestically and $69,817 internationally for a total of $583,264.” And then it was gone.

Yet, for all the force and power that The One I Love possesses, it might as well not have been made at all, so quickly did it disappear. As Wikipedia notes, after a well received screening at the Sundance Film festival on January 21, 2014, “The One I Love opened in a limited release [on August 22, 2014] in the United States in 8 theaters and grossed $48,059 with an average of $6,007 per theater and ranking #42 at the box office. The film’s widest release was 82 theaters and it ended up earning $513,447 domestically and $69,817 internationally for a total of $583,264.” And then it was gone.

That’s a shame, because The One I Love is both original and unsettling, even as it incorporates themes, either by design or simply through coincidence, from John Cromwell’s The Enchanted Cottage (1945), tinged with the much darker vision of Mary Dexter’s The Day Mars Invaded Earth (1963), with touches of Spike Jonze’s Being John Malkovich (1999) and Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) thrown in for added resonance.

The One I Love starts off in a seemingly predictable manner, as if the film will be another earnest study of a marriage in collapse, in the manner of Mike Nichols’ film of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966, which is actually referenced in the film’s dialogue), but soon any clinical realism is abandoned for a far more sinister and elliptical scenario – a kind of dark “magical realism” – in which the audience is never sure about the characters’ motives, or even their putative identities.

Not surprisingly, Ethan and Sophie are experiencing a moment of crisis in their relationship as a result of Ethan’s infidelity, and their smooth and all-too-affable therapist (effortlessly played by Ted Danson) suggests that they spend a weekend at a therapeutic retreat to “reconnect.” At first, when the couple arrives at the lavishly appointed estate, which is to be their home for the next few days, all seems well. It’s a rather odd place, overflowing with flowers and lavishly decorated throughout, with a guest book in the front hallway attesting to the salutary effect it has had on the previous couples who have stayed there.

Not surprisingly, Ethan and Sophie are experiencing a moment of crisis in their relationship as a result of Ethan’s infidelity, and their smooth and all-too-affable therapist (effortlessly played by Ted Danson) suggests that they spend a weekend at a therapeutic retreat to “reconnect.” At first, when the couple arrives at the lavishly appointed estate, which is to be their home for the next few days, all seems well. It’s a rather odd place, overflowing with flowers and lavishly decorated throughout, with a guest book in the front hallway attesting to the salutary effect it has had on the previous couples who have stayed there.

Yet soon it becomes apparent that something is subtly wrong; the guesthouse behind the property seems to serve as some sort of “magic zone” where both Sophie and Ethan, given to bickering over the most minor slights, suddenly are transformed into loving, caring people – but it’s all an illusion. For when Ethan is in the cottage, the “Sophie” he sees isn’t his wife, but a doppelganger (also played by Moss) who seems receptive to his every suggestion, kind and forgiving – and when Sophie enters the guesthouse, “Ethan” (Duplass again) is similarly kind and self-effacing – but it isn’t “Ethan” at all. Who, then, are these people, and what the hell is going on?

We never find out precisely, even as the couple’s visits to the cottage become more and more frequent, as they find that they are much more comfortable with their

“impostor” opposites than their real mates, simply because the “doubles” are more or less idealized versions of what Sophie and Ethan are in real life. Without flaws, smooth talking and soothing, these impostors seem to offer a dream relationship to each partner – that is, if the other partner can be discarded.

At first, the false “Sophie” appears only to Ethan, and the false “Ethan” only to Sophie, but about halfway through the film, the impostors drop any sort of pretense and come out into the open as a couple, all the better to torment their “human” counterparts. But yet they insist on their own reality; as far as they’re concerned, they’re not impersonating anyone. As matters progress, the real Sophie, for her part, seems much more attracted to the false Ethan than the real one; the false Ethan is perceptive, warm, affectionate, and witty – and he’s also good in the sack.

At first, the false “Sophie” appears only to Ethan, and the false “Ethan” only to Sophie, but about halfway through the film, the impostors drop any sort of pretense and come out into the open as a couple, all the better to torment their “human” counterparts. But yet they insist on their own reality; as far as they’re concerned, they’re not impersonating anyone. As matters progress, the real Sophie, for her part, seems much more attracted to the false Ethan than the real one; the false Ethan is perceptive, warm, affectionate, and witty – and he’s also good in the sack.

But as The One I Love enters its final act, the real Ethan discovers that the whole thing is a set-up so that some unnamed and unknown entity can replace them both in the outside world, for reasons that remain unclear to the end of the film. And then he finds to his horror that he can no longer distinguish between the false Sophie and the real one, even as he plans his escape from the “idyllic” compound.

All of this could have been predictable science fiction filmmaking, as in The Day Mars Invaded Earth, cited by Susan Sontag in her groundbreaking essay “The Imagination of Disaster,” in which a rather well to do American family are “replaced” in the general population by Martians who take over their bodies – a familiar trope that goes back to the dawn of the cinema, in numerous iterations, but that’s not what’s happening here.

Sophie and Sophie both exist, just as Ethan and Ethan both exist, and for the middle third of the film, while they seem to interact uneasily with each other, all four have their own separate identities, even if they look exactly alike. But when the final crunch comes, it’s unclear what the concept of “identity” really means here, and who is really the “authentic” figure.

As Sontag notes of similar films with this theme of transubstantiation:

As Sontag notes of similar films with this theme of transubstantiation:

“[T]he rule, of course, is that this horrible and irremediable form of murder [the obliteration of another person’s identity] can strike anyone in the film except the hero. The hero and his family, while grossly menaced, always escape this fact and by the end of the film the invaders have been repulsed or destroyed. I know of only one exception, The Day That Mars Invaded Earth (1963), in which, after all the standard struggles, the scientist-hero, his wife, and their two children are ‘taken over’ by the alien invaders – and that’s that.”

But that’s much too schematic for The One I Love – the roles, and the stakes, change from moment to moment, and even when you think you have a handle on a scene – it’s going this way, you think, and you can sense the outcome – more often than not, that scene doubles back on itself to reveal an entirely new balance of power and level of meaning – something that most films deliberately avoid in this era of “leave no audience member behind.”

The One I Love thus unspools in a measured, leisurely manner, not aiming for shock tactics, but rather being a game of the mind, as in Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), though again, that’s not what’s happening here, either. I’ll leave the rest for you to find out, but suffice it to say that the film ends with more questions and loose ends than answers, something that’s entirely satisfactory to me. But for most viewers, apparently, this is a problem, not a plus.

Even someone as perceptive as Todd McCarthy, the longtime film critic for Variety and now The Hollywood Reporter, wrote in his review of The One I Love that “on a moment-to-moment basis, this smoothly made film can be incredibly trying, even annoying, to watch, due to the grueling repetitiveness of the scenes and dialogue and the claustrophobia of the paradoxically beautiful setting.”

I remember numerous critics saying the same thing about Godard’s Le Mépris (1963), a film that also used “grueling repetitiveness of the scenes and dialogue and the claustrophobia of the paradoxically beautiful setting” of Capri to tell its tale of a marriage in similar free-fall. While the two films are in many ways completely different, the questions of who we are when we’re by ourselves, and who we are when we’re with others, continue to resonate long after the last image of both films has faded from the screen.

The real trick with The One I Love – and why it works so well – is that it seems to be one thing, and turns out to be something altogether different, much like the characters within the film itself. So then it becomes a problem; how can you sell a film like that, without resorting to gimmickry – and it should be noted that the film’s trailer is a masterpiece of deception. How can you let people know what they’re in for, without giving away too much?

In Jonathan Glazer’s Under The Skin (2013), for example, much of the film’s publicity centered on the film’s central conceit of “alien being” Scarlett Johansson driving around in a truck picking up strange men in Scotland, but that really tells you nothing about the film at all – just as “it’s a film about two women, one who never says anything, and one who never shuts up” tells you nothing about Persona (which was actually the one-line summary Bergman used to obtain financing for that film).

As director McDowell told critic Austin Trunick of Under The Radar of the difficulty of marketing The One I Love, “I didn’t know how we were going to do it, but we moved forward just to see if we could. And we’ve kind of used that as the marketing for the movie, which is, ‘Here’s the tone and the world. It’s a romantic comedy with a twist. Something happens, but we’re not going to tell you what. Please go watch the movie.’”

So now I’m telling you the same thing. Despite all that I have outlined here, you really won’t get a sense of the film’s accomplishment, or ambition, or it’s dreamy, sensual sense of dread and unease unless you experience it for yourself, in a very compact 91 minutes. But, as I said at the beginning of this piece, The One I Love is yet another film “lost in the cosmos,” a film on the VOD channel that most viewers will never see. As McDowell noted, The One I Love was sold, of all things, as a “romantic comedy” – and believe me, nothing could be further from any sort of truth. See for yourself. This one is a keeper, and a really significant accomplishment.

So now I’m telling you the same thing. Despite all that I have outlined here, you really won’t get a sense of the film’s accomplishment, or ambition, or it’s dreamy, sensual sense of dread and unease unless you experience it for yourself, in a very compact 91 minutes. But, as I said at the beginning of this piece, The One I Love is yet another film “lost in the cosmos,” a film on the VOD channel that most viewers will never see. As McDowell noted, The One I Love was sold, of all things, as a “romantic comedy” – and believe me, nothing could be further from any sort of truth. See for yourself. This one is a keeper, and a really significant accomplishment.

My sincere thanks to Ian Olney and Gwendolyn Audrey Foster for alerting me to this excellent film, which I would otherwise have surely missed. Tak!

Wheeler Winston Dixon is the James Ryan Professor of Film Studies, Coordinator of the Film Studies Program, and Professor of English at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. His newest books are Cinema at the Margins (2013), Streaming: Movies, Media and Instant Access (2013); and Death of the Moguls: The End of Classical Hollywood (2012). Dixon’s book A Short History of Film (2008, co-authored with Gwendolyn Audrey Foster) was reprinted six times through 2012. A second, revised edition was published in 2013; the book is a required text in universities throughout the world. His newest book, Black & White: A Brief History of Monochrome Cinema, is forthcoming from Rutgers University Press in 2015.

References

McCarthy, Todd (2014), “The One I Love: Sundance Review”, The Hollywood Reporter, 23 January.

Sontag, Susan (1965), “The Imagination of Disaster”, Commentary, 1 October.

Trunick, Mark (2014), “Director Charlie McDowell Discusses The One I Love”, Under The Radar, 22 August.