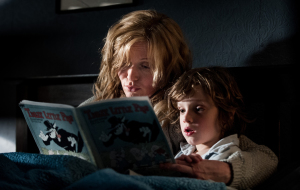

Australian filmmaker Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook is last season’s fascinating, much-discussed contribution to the horror film, a genre that has fallen on hard times in the last quarter-century. I find the film engaging, although my enthusiasm is qualified. It is incoherent at the narrative and ideological levels, succeeding in terms perhaps not quite anticipated by the artist. The apparent basis of the film’s psychological horror is the holding-back of grief caused by trauma – the sudden loss of a husband/father in a car crash as he takes his wife to the hospital, where she will give birth to their first child, a son. At the heart of this film is the displacement of sexual pleasure by parental duty, and the suffocation of the female by this duty, a constant reminder of her status as object for the male’s pleasure rather than a participant in pleasure. In the ensuing narrative, the widowed mother goes insane as she rears her boy – seven years old when the narrative fully begins – as the film tries to draw its horror from the pressures imposed on a single-parent household run by a woman.

The idea of using sudden emotional trauma as the springboard for the development of psychological horror seems to me questionable both in its ideological assumptions and general effectiveness. Certainly there are deep traumas that haunt people for a lifetime (Nazi Holocaust survivors). Most of us have suffered a form of trauma at some point of life (the sudden loss of a loved one, divorce, dismissal from a job). As with many psychological ills, trauma can be the subject of denial, sometimes leading a person into compulsive, self-destructive behavior. But one rarely conjoins, I think, the word “trauma” with “repression,” the word used by some reviewers (and the filmmakers) in discussing The Babadook. In short, emotional trauma and its aftermath seems a weak device to undergird and justify psychological horror.

Repression, as I have come to understand the word as used in cultural discourse, suggests a long-term process of limiting a person’s desires, especially sexual fulfillment (which would include the creative urge, not always a form of sublimation) and sexual independence, largely due to conditions deeply engrained in the individual and her/his civilization. Repression became central to the horror film as it moved into its psychological era (although one can argue that the genre was always involved in the psychological, since The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari [1919] onward). Norman Bates in Psycho (1960) is the product of lifelong repression/oppression in the family unit, producing a perpetual (very deadly) child, one whose sex drive is extremely deformed. The Birds (1963) has similar concerns, with the Brenner family a site of castration of the male child, sexual frustration of both male and female, and the hysteria of the mother after the death of the patriarch. Repression, as has long been noted, is the internalizing of social laws regarding sexual conduct and the working of the family; oppression is the enforcement of laws and mores, and the channeling of sexual energies, by external forces (church, school, job, the family structure itself).

Repression, as I have come to understand the word as used in cultural discourse, suggests a long-term process of limiting a person’s desires, especially sexual fulfillment (which would include the creative urge, not always a form of sublimation) and sexual independence, largely due to conditions deeply engrained in the individual and her/his civilization. Repression became central to the horror film as it moved into its psychological era (although one can argue that the genre was always involved in the psychological, since The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari [1919] onward). Norman Bates in Psycho (1960) is the product of lifelong repression/oppression in the family unit, producing a perpetual (very deadly) child, one whose sex drive is extremely deformed. The Birds (1963) has similar concerns, with the Brenner family a site of castration of the male child, sexual frustration of both male and female, and the hysteria of the mother after the death of the patriarch. Repression, as has long been noted, is the internalizing of social laws regarding sexual conduct and the working of the family; oppression is the enforcement of laws and mores, and the channeling of sexual energies, by external forces (church, school, job, the family structure itself).

The (limited) importance of The Babadook flows from its examination of the mother and her relationship with her young son, not solely the memory of the husband/father’s death in a car crash. After all, the most interesting parts of the film concern the mother, her increasing neurosis-to-psychosis, and the role of her son in causing the psychosis. Insofar as the film depends on and reiterates the car-crash trauma, it gets into trouble, emphasizing the innate insanity, or at least fragility and instability, of the female, and her incompetence as a parent, especially as Amelia, the berserk harridan with wild hair and frightening expression, becomes dominant. I tend to see the film as an examination of the monogamous married couple and its discontents, the discontents of parenthood, the pervasive authority of patriarchal law, and the complex, repressed sexual desires that are the inevitable consequence of all these institutions and assumptions.

The Bedroom

Early in the film we see the car crash re-experienced by Amelia (Essie Davis) in a nightmare. We see her breathing deeply in her car seat, the activity commonly associated with the last moments of pregnancy. Suddenly glass flies as the crash happens, as Amelia is knocked about. There is an important shot in this sequence. Amelia looks at her husband Oskar (Benjamin Winspear) just before he is decapitated. He sits rather slumped as he drives the car, a look of boredom or depression on his face as I read it. I can only read the shot as the husband’s unhappiness with the whole situation. We hear Amelia later in the film, as her madness grows, express her hatred of her son, her wish that he had perished rather than her husband. But that single shot of the bored husband provoked my question: did both parents not want a child? Oskar’s fed-up expression tends to lead one to such a conclusion. We can perhaps set this question aside, since later in the film Oskar appears in a vision to a deteriorating Amelia, asking for his son as he caresses her. The son becomes an instrument of the father. What is crucial is the establishing of the sexual/emotional tension informing the couple’s relationship, and the increased sexual frustration in Amelia after she is widowed.

During the nightmare of the crash, as Amelia imagines herself being thrown about in the car, we hear a child’s voice calling out “mom!” Is the voice calling from the womb? Of course it is the voice of her son in the present, ending her nightmare. While the son might be said to “save” the mother from her nightmare/bad memories, one can also point to the child as encumbrance, an impediment to the sexual relation of male-female, even in this deadly moment. The boy’s constant demands are blamed for the mother’s frustration, explicitly so in a scene where she tries for small sexual gratification.

During the nightmare of the crash, as Amelia imagines herself being thrown about in the car, we hear a child’s voice calling out “mom!” Is the voice calling from the womb? Of course it is the voice of her son in the present, ending her nightmare. While the son might be said to “save” the mother from her nightmare/bad memories, one can also point to the child as encumbrance, an impediment to the sexual relation of male-female, even in this deadly moment. The boy’s constant demands are blamed for the mother’s frustration, explicitly so in a scene where she tries for small sexual gratification.

At the end of Amelia’s nightmare, we see her floating above her bed (The Exorcist and The Shining, with other films, are cited incessantly, making this too much a cinephile’s film). The bed is important, the now-unused (for sex) marital bed, a place to which Amelia retires for sleep, escape, and isolation – especially from her son Samuel (Noah Wiseman). Amelia’s sexual frustration is apparent. She notes a couple making love in a parked car. She watches late-night television featuring phone-sex advertisements, and moments of lovemaking from 1960s melodrama. She goes to her bedroom, taking a vibrator from her keepsakes as she gets into bed. She masturbates, but just as she approaches orgasm Samuel jumps on the bed, shouting that the Babadook is about – here the bogeyman is a clear emblem of male-imposed oppression. The bedroom is also central to the final dissolution of the female (before her tentative “recovery”), as the Babadook/male presence turns the room into a site of terror rather than pleasure.

Although mother and son pledge themselves to each other (Samuel’s “I love you, mum, and I always will”), their relationship gives the film its horror by their continued mutual aggression. Samuel creates a sort of portable catapult with which he will fight the monsters of his imagination – his first act with the weapon is to break a window in the domicile; Amelia eventually wields a knife. Yet there is an incestuous undertow, at least early in the film, suggesting the son as embodiment of the father, such as when Samuel, clad in his magician’s outfit, gently caresses his mother’s cheek as a lover might. When he gives her a warm embrace, Amelia shoves him away, as if recognizing the hug’s erotic quality. The polymorphous perverse haunts the film up to a point, after which the female’s insanity becomes dominant. The son’s status as reminder of male erotic power is replaced by the male’s sadism.

Although mother and son pledge themselves to each other (Samuel’s “I love you, mum, and I always will”), their relationship gives the film its horror by their continued mutual aggression. Samuel creates a sort of portable catapult with which he will fight the monsters of his imagination – his first act with the weapon is to break a window in the domicile; Amelia eventually wields a knife. Yet there is an incestuous undertow, at least early in the film, suggesting the son as embodiment of the father, such as when Samuel, clad in his magician’s outfit, gently caresses his mother’s cheek as a lover might. When he gives her a warm embrace, Amelia shoves him away, as if recognizing the hug’s erotic quality. The polymorphous perverse haunts the film up to a point, after which the female’s insanity becomes dominant. The son’s status as reminder of male erotic power is replaced by the male’s sadism.

The Monster

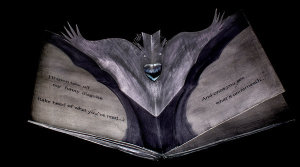

The film’s title comes from a storybook Amelia finds in her son’s room entitled “Mister Babadook.” She doesn’t recognize it, implying that her son brought it into the house as an instrument to cause her torment. This is a problematical area of the film, since many events veer away from a solid anchoring in family life and realism to take us into the fantastic, implying that the family issues are affected by something supernatural. Such scenes make one ask: “Is everything a dream? Is it all fantastic? The Babadook book had to be purchased by Amelia, since it is unlikely that the little boy bought such an expensive book on his own. The film tempts us with the silly notion that a supernatural force put the book in the house. Several events involving the Babadook book are irksome, such as its reappearance after Amelia destroys it. Worse, her going to the police to complain about someone constantly leaving the offensive book in her house (after she has burned it in the barbeque, obliterating it as evidence) suggests her lack of common sense. Is it all a bad dream? If one decides to focus on what seems real, the film’s virtues assert themselves. Amelia is often portrayed as powerless in the face of patriarchal authority, as in the police station scene, or when she is forced to deal with confrontational school authorities angered by Samuel’s violence. Amelia’s oppression is external (the authority figures) and internal (her son as reminder of her past sex life).

The film’s title comes from a storybook Amelia finds in her son’s room entitled “Mister Babadook.” She doesn’t recognize it, implying that her son brought it into the house as an instrument to cause her torment. This is a problematical area of the film, since many events veer away from a solid anchoring in family life and realism to take us into the fantastic, implying that the family issues are affected by something supernatural. Such scenes make one ask: “Is everything a dream? Is it all fantastic? The Babadook book had to be purchased by Amelia, since it is unlikely that the little boy bought such an expensive book on his own. The film tempts us with the silly notion that a supernatural force put the book in the house. Several events involving the Babadook book are irksome, such as its reappearance after Amelia destroys it. Worse, her going to the police to complain about someone constantly leaving the offensive book in her house (after she has burned it in the barbeque, obliterating it as evidence) suggests her lack of common sense. Is it all a bad dream? If one decides to focus on what seems real, the film’s virtues assert themselves. Amelia is often portrayed as powerless in the face of patriarchal authority, as in the police station scene, or when she is forced to deal with confrontational school authorities angered by Samuel’s violence. Amelia’s oppression is external (the authority figures) and internal (her son as reminder of her past sex life).

The Babadook is the archetypal bogeyman who threatens from closets and darkened doorways, a very tired device for reminding us that all is not well in the household. (The book itself looks far too arty in its Expressionist aspect, flaunting production design.). Mister Babadook looks like Caligari, or Lon Chaney from Tod Browning’s lost London after Midnight. (I would note that the Babadook, in some of the book drawings, also looks like a black-faced minstrel; further study of the film might explore its racial dimension, and Australian white culture’s alternating valorization/demonization of the Aboriginal culture and population.)

The Babadook, Samuel, and the father’s apparition (to Amelia) seem to be one, working in tandem to oppress the mother. In his magician’s costume, Samuel resembles the Babadook. Yet Samuel recognizes the Babadook’s constant presence; in such moments it seems that the film uses the monster as a symbol of Amelia’s ongoing grief, which Samuel senses and wants to dispel. Seen this way, Samuel’s anger might be read simply as an extension of his mother’s grief and isolation, depriving him of her full affection.

The Babadook, Samuel, and the father’s apparition (to Amelia) seem to be one, working in tandem to oppress the mother. In his magician’s costume, Samuel resembles the Babadook. Yet Samuel recognizes the Babadook’s constant presence; in such moments it seems that the film uses the monster as a symbol of Amelia’s ongoing grief, which Samuel senses and wants to dispel. Seen this way, Samuel’s anger might be read simply as an extension of his mother’s grief and isolation, depriving him of her full affection.

But other questions arise. What, after all, is the source of Samuel’s problems, his apparent mental illness? Samuel was in the womb at the time of the crash, so obviously he didn’t experience trauma unless one accepts inter-uterine disturbance. But Samuel is fully aware of the car crash and speaks of it almost in a rote manner. At a supermarket, he tells a woman that his dad is “in the cemetery because he got killed driving mom to the hospital to have me.” The moment suggests that Amelia has been brow-beating the boy since very early childhood, reminding him that he is a by-product of sex acts of which she is now deprived, although she is obliged to do her duty as mother of the male child/patriarchal heir.

The aggression of Samuel, accompanying the idea that he is a weapon of the father’s revenge and patriarchal dissatisfaction with female conduct, becomes a constant. He tells his mother that the Babadook “will eat [your] insides.” He throws a screaming fit, causing Amelia to crash her car. Amelia finds glass in her soup – Samuel insists on the Babadook’s presence, but could the glass be anything but the action of the child? His immersion in magic and monsters seems both a means of escape and early sexualization. He makes dangerous weapons, including a crude crossbow, alarming the school authorities. When Amelia takes from Samuel one of Oskar’s possessions, he shouts “He’s my dad – you don’t own him!”

The aggression of Samuel, accompanying the idea that he is a weapon of the father’s revenge and patriarchal dissatisfaction with female conduct, becomes a constant. He tells his mother that the Babadook “will eat [your] insides.” He throws a screaming fit, causing Amelia to crash her car. Amelia finds glass in her soup – Samuel insists on the Babadook’s presence, but could the glass be anything but the action of the child? His immersion in magic and monsters seems both a means of escape and early sexualization. He makes dangerous weapons, including a crude crossbow, alarming the school authorities. When Amelia takes from Samuel one of Oskar’s possessions, he shouts “He’s my dad – you don’t own him!”

Amelia meets a supportive co-worker named Robbie (Daniel Henshall), a very undeveloped character. He would seem to be a potential sex partner, but he disappears from the narrative – but not until after Samuel tells him “she won’t let me have a birthday party and she won’t let me have a dad,” suggesting that the mother’s extreme depression has drained away her eroticism and all joy from the boy’s life.

Death, Castration, the Child

Amelia’s job in a nursing home suggests she is surrounded by a world of death that she very consciously embraces. The elderly are portrayed as superannuated creatures in very static images. The dreariness of such scenes is palpable. Amelia’s insomnia and ongoing depression are caused, it seems, less by her traumatic memories than her own son’s disobedience and refusal to leave her alone. In the most shocking scene, an exhausted Amelia’s sleep is interrupted by pleas from her hungry son, plaintively asking for a meal. Amelia darts up from her bed, telling Samuel to “eat shit.” Although she apologizes, the verbal and physical violence continue, emphasizing the son’s desire to capture/kill the mother, the mother’s desire to kill/castrate the male. Amelia visits the basement and a dark upstairs room (the psychological symbolism perhaps too obvious). In her journey into the unconscious, Oskar reappears. His first appearance has an erotic aspect, promising comfort to Amelia after which he demands the child. In the second appearance, Amelia re-visions his decapitation, suggesting the accident as her willed castration of Oskar, and a possible end to her bad memories, which have at their root the lure of male sexuality. As the apocalyptic finale approaches, a thoroughly crazed Amelia finds herself tied up in baroque knots in the basement. The house itself shows signs of distress as the freed Amelia holds her son and screams at the now thoroughly manifest, gigantic Babadook to leave them alone. The monster suddenly deflates, as we are led to an obviously false ending suggesting that Amelia’s preoccupation with her dead husband has ended.

Amelia’s job in a nursing home suggests she is surrounded by a world of death that she very consciously embraces. The elderly are portrayed as superannuated creatures in very static images. The dreariness of such scenes is palpable. Amelia’s insomnia and ongoing depression are caused, it seems, less by her traumatic memories than her own son’s disobedience and refusal to leave her alone. In the most shocking scene, an exhausted Amelia’s sleep is interrupted by pleas from her hungry son, plaintively asking for a meal. Amelia darts up from her bed, telling Samuel to “eat shit.” Although she apologizes, the verbal and physical violence continue, emphasizing the son’s desire to capture/kill the mother, the mother’s desire to kill/castrate the male. Amelia visits the basement and a dark upstairs room (the psychological symbolism perhaps too obvious). In her journey into the unconscious, Oskar reappears. His first appearance has an erotic aspect, promising comfort to Amelia after which he demands the child. In the second appearance, Amelia re-visions his decapitation, suggesting the accident as her willed castration of Oskar, and a possible end to her bad memories, which have at their root the lure of male sexuality. As the apocalyptic finale approaches, a thoroughly crazed Amelia finds herself tied up in baroque knots in the basement. The house itself shows signs of distress as the freed Amelia holds her son and screams at the now thoroughly manifest, gigantic Babadook to leave them alone. The monster suddenly deflates, as we are led to an obviously false ending suggesting that Amelia’s preoccupation with her dead husband has ended.

In the final moments, mother and son have a pleasant visit with social workers, who are clueless as to all that has transpired. Mother and son then sit in their garden, where Samuel performs new magic tricks for Amelia. But Amelia revisits the basement/unconscious, offering a meal of worms to the monster/obsession. She is almost pulled into the darkness by the Babadook, showing us that her obsession with the husband/death is still unresolved.

Against The Babadook

The film is a dark fascination, but it appears to me now not well thought-through, its psychological issues hinted at rather than explored. Is Amelia paralyzed by the sorrow-filled memory of her dead husband and the sex life they enjoyed, or does she see the husband as essentially monstrous (the Babadook)? Is the Babadook merely a reminder that “things are not right”? If so, this is a very thin horror device indeed. Much appears too fantastic, and to the detriment of the female, whose image has not fared well in many horror films. The image that is reasserted constantly is that of the wildly insane female, the “hysteric,” as Essie Davis’s contortions and grimaces become more extreme and threatening than the bogeyman, perhaps because the female is once again envisioned as too emotional, too inherently unstable, and always the real source of horror; after all, female craziness is a mainstay of the cinema. At one point Amelia imagines herself as a witch, and as the subject of a news program about a woman who stabbed her son to death (the destruction of the desexualizing, burdensome reminder of domestic life seems the logical denouement, but the film opts for the mother trying to return to impossible parental duties). Worse, Amelia is utterly incapable of helping herself; she refuses other sex partners even seven years after her husband’s death (asserting the hoary idea of husband as “one true love”), and, perhaps more important, any form of female solidarity and support. At a birthday party, Amelia sits apart from a group of women, a few of whom speak of their own sufferings and disappointments, as well as childbirth. We see them as a static unit from Amelia’s point of view. In Amelia’s eyes they are all well-coiffed, well-off, empty-headed simpletons. The moment might work as a criticism of a certain kind of middle-class self-absorption, but where in the film is there a positive image of the female? One of the social workers visiting Amelia has long, pointed features that the camera lingers on, ignoring her male partner – here the film uses a woman’s physical appearance to assert the “witch” merely as homely woman, and the evil presence within the world of the film as, finally, female. Even Amelia’s mother-in-law, the kindly Aunt Claire (Hayley McElhinney) eventually comes across as a cloying, mawkish, intrusive pest. Potentially interesting characters like Robbie are undeveloped and dropped.

The film is a dark fascination, but it appears to me now not well thought-through, its psychological issues hinted at rather than explored. Is Amelia paralyzed by the sorrow-filled memory of her dead husband and the sex life they enjoyed, or does she see the husband as essentially monstrous (the Babadook)? Is the Babadook merely a reminder that “things are not right”? If so, this is a very thin horror device indeed. Much appears too fantastic, and to the detriment of the female, whose image has not fared well in many horror films. The image that is reasserted constantly is that of the wildly insane female, the “hysteric,” as Essie Davis’s contortions and grimaces become more extreme and threatening than the bogeyman, perhaps because the female is once again envisioned as too emotional, too inherently unstable, and always the real source of horror; after all, female craziness is a mainstay of the cinema. At one point Amelia imagines herself as a witch, and as the subject of a news program about a woman who stabbed her son to death (the destruction of the desexualizing, burdensome reminder of domestic life seems the logical denouement, but the film opts for the mother trying to return to impossible parental duties). Worse, Amelia is utterly incapable of helping herself; she refuses other sex partners even seven years after her husband’s death (asserting the hoary idea of husband as “one true love”), and, perhaps more important, any form of female solidarity and support. At a birthday party, Amelia sits apart from a group of women, a few of whom speak of their own sufferings and disappointments, as well as childbirth. We see them as a static unit from Amelia’s point of view. In Amelia’s eyes they are all well-coiffed, well-off, empty-headed simpletons. The moment might work as a criticism of a certain kind of middle-class self-absorption, but where in the film is there a positive image of the female? One of the social workers visiting Amelia has long, pointed features that the camera lingers on, ignoring her male partner – here the film uses a woman’s physical appearance to assert the “witch” merely as homely woman, and the evil presence within the world of the film as, finally, female. Even Amelia’s mother-in-law, the kindly Aunt Claire (Hayley McElhinney) eventually comes across as a cloying, mawkish, intrusive pest. Potentially interesting characters like Robbie are undeveloped and dropped.

The Babadook merits revisiting since it at least offers the horror film to us as adult-oriented art, not the typical, effects-driven spectacle that has overtaken the genre. The single mother and the domestic scene are ideal subjects for the horror film’s further exploration, the family being the “first true battlefield,” in the words of Michael Haneke. If The Babadook feels thin after repeated viewings, it at the least deserves applause for its considerable, if faltering, ambition.

Christopher Sharrett is Professor of Communication and Film Studies at Seton Hall University. He writes often for Film International.