A Book Review by John Duncan Talbird.

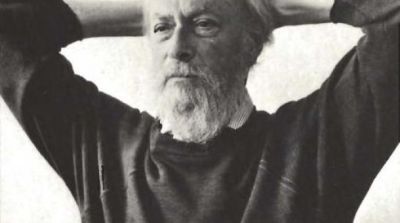

Don Carpenter killed himself in 1995. He was a writer’s writer, never famous for the ten or so novels, dozens of stories, or screenplays he wrote and published from the sixties to the late eighties. In the 1960s, when he was first publishing and garnering attention, he wasn’t experimental enough to be appreciated by those celebrating Donald Barthelme, Robert Coover, and William Gass. His brand of realism was not the rich and layered realism of Updike, Bellow, or Roth and it would be another ten years before America discovered the dirty realism of Raymond Carver (another writer who, like Carpenter, spent his formative years in the Pacific Northwest) and his crowd. But there’s been renewed interest in Carpenter’s writing in the last few years. The NY Review of Books rereleased Carpenter’s celebrated first novel, Hard Rain Falling, a few years ago, and in the spring of 2014 independent Berkeley imprint Counterpoint Press released Carpenter’s last uncompleted novel, Fridays at Enrico’s, completed and championed by Jonathan Lethem.

Now Counterpoint has re-released three of Carpenter’s novels, A Couple of Comedians (1979), The True Life Story of Jody McKeegan (1975), and Turnaround (1981) in a single volume that they’re calling The Hollywood Trilogy. Many readers of Film International may be more familiar with Carpenter as the screenwriter for the underappreciated Hollywood Renaissance-era film, Payday (1973) starring Rip Torn. In fact, Carpenter was uniquely positioned to write about Hollywood as both an insider and an outsider – an English teacher who wrote fiction on the side and then a fiction writer who wrote screenplays on the side, several of his projects ending up in turnaround, that black hole for stories whose producers have squandered their resources until there’s nothing left to show. Carpenter probably had some real grievances to air and some axes to grind, but what’s startling about these three novels is their decentness, their humanity. Even the villains are complex in these books. The people you want to hate are three-dimensional and understandable. They may exploit others, but you see their deep-down desire to do the right thing and most of all, you see their love for the movies, the movies that you watch, again and again. Even the exploiters are often pathetic, sad little boys whose mothers or fathers didn’t love them enough.

Now Counterpoint has re-released three of Carpenter’s novels, A Couple of Comedians (1979), The True Life Story of Jody McKeegan (1975), and Turnaround (1981) in a single volume that they’re calling The Hollywood Trilogy. Many readers of Film International may be more familiar with Carpenter as the screenwriter for the underappreciated Hollywood Renaissance-era film, Payday (1973) starring Rip Torn. In fact, Carpenter was uniquely positioned to write about Hollywood as both an insider and an outsider – an English teacher who wrote fiction on the side and then a fiction writer who wrote screenplays on the side, several of his projects ending up in turnaround, that black hole for stories whose producers have squandered their resources until there’s nothing left to show. Carpenter probably had some real grievances to air and some axes to grind, but what’s startling about these three novels is their decentness, their humanity. Even the villains are complex in these books. The people you want to hate are three-dimensional and understandable. They may exploit others, but you see their deep-down desire to do the right thing and most of all, you see their love for the movies, the movies that you watch, again and again. Even the exploiters are often pathetic, sad little boys whose mothers or fathers didn’t love them enough.

And these are boys’ stories. There is a subtle, and sometimes not-so-subtle, misogyny that runs through these books. In the first novel, A Couple of Comedians, there is an ugly little scene early on where the narrator of the novel, David Ogilvie, rapes Sonny, a young actress. She says, “That wasn’t very nice,” he responds, “I guess you’re right” (61) and then, pretty much nothing happens. In the next scene they make love and then after that, they act a bit lovey-dovey, holding hands, etc. The “romance” doesn’t last, they drift apart by novel’s end. We don’t know if it’s because she can’t get over the fact that she’s been raped (we don’t get her perspective other than Ogilvie’s observation, “I didn’t know how Sonny felt because I never know how other people feel, but she looked all rosy and clung to me and seemed to radiate hot love for me…” [62]). It’s even a little hard to know if Carpenter is aware that this is a rape scene, because ultimately the book is not concerned with Sonny or any of the other many women that both comedians of the title – a duo who seem to be a cross between Martin and Lewis and Cheech and Chong – screw along the way. The book is about the sexless love affair between the two performers, Ogilvie and Jim Larson. Jim is apparently having a mental breakdown and he disappears. The second half of the book is a long flashback wherein Ogilive reminisces about his relationship with Jim, biting his nails and spitting the shards, waiting for his partner to appear so that they can go on stage in a Las Vegas nightclub. It’s a strange, almost plotless book and so it’s a surprise that, in the end, Carpenter seems to make it all work, tying things together in a reasonably satisfying manner. But that rape scene…

Is he just describing the clear misogyny of the Hollywood industry where women – especially in the 70s, though it’s not a whole lot better even today – are mostly without any decision-making positions, just pretty faces with increasingly short shelf lives? Is he, in 1979, like the rest of Hollywood, the last to hear about what’s happening in the real world, that something which would be called second-wave feminism is going on throughout America and much of the developed world? After reading the second book in this collection, I have to give Carpenter the benefit of the doubt. The True Life Story of Jody McKeegan is a superbly drawn sketch of a young actress becoming an old – at least for Hollywood – actress at the age of thirty-five still waiting for her big break. In fact, I would say that the first half of this novel is the best writing in the entire trilogy and it’s not even set in Hollywood, but in Portland, Oregon. Here, Carpenter captures the fantasy of the easy-fix that many young people who live impoverished lives imagine, the escape into acting or sports, the metamorphosis from anonymity to celebrity. This novel tells the formative story of the titular character, including her older sister, the beauty of the family (Jody is awkward and “ugly,” though she’s clearly the smarter of the two) as they grow up in the mean streets of Portland. Jody’s sister, Lindy, wants to be a movie star, but she has difficulty figuring out how to make it happen, stuck in a dead-end relationship with a traveling salesman and drug addict in the Pacific Northwest. She gets pregnant, not by the salesman; I won’t say by whom in order not to ruin Carpenter’s perverse little plot twist, but I will say that the description of the back-alley abortion provider is some of the most vivid writing in the entire trilogy. In fact, the details are so surprising and realistic – it actually takes place in a house in the suburbs, not really in an alley – that the second half of the book, mostly set in the environs of Hollywood and on location in Alabama, seems muted and bland by comparison. Which made me think as I read this second book: Is this the point? That Carpenter’s experience of Hollywood was boring and so pretty much all descriptions of Hollywood are boring? People waiting around for something to happen and when it happens we all miss it if we blink? Scene after scene of actors drinking champagne and smoking pot and snorting coke? Carpenter ably shows the emptiness and tedium of the alcoholic and drug life, so vivid in its repetitiveness and boredom. He’s so successful at rendering boredom that he often simply bores.

Turnaround, the last novel in the trilogy, is the most complex and engaging and, I think, really the only true Hollywood novel amongst the three. Here, we get the true Hollywood – or, at least, a true Hollywood – in all its facets. Carpenter splits this final tale between three characters: 1) Jerry Rexford, the hero of this novel, a young writer trying to make it in Hollywood, 2) Alexander Hellstrom, a virile, fifty-something movie exec, the number-two man at a major movie studio, and 3) Richard Heidelberg, the villain of this story, a young, first-movie Academy Award-winning writer-director (he won for screenplay, of course) who believes everything the press has said about him though he clearly has no new ideas. We alternate from chapter to chapter between these characters and though it’s no surprise that their trajectories will converge, the novel is still suspenseful as we see who will screw over whom and who will surprise us with his decentness and his preference for art over industry.

What seems to be the closest we get to an autobiographical moment in these books happens near the end of Turnaround. Jerry Rexford has gotten his big break, the studio has optioned his screenplay, a remake of Chandler’s The Lady in the Lake. It’s one of the funniest moments too. Some exec tells Jerry that he needs to change a scene in his script, that it will be too expensive to run a car off a cliff:

Somebody suggested that the character should, instead of driving off a cliff, run into a tree.

“What’s the advantage of that?” Jerry wanted to know.

Easier to control, he was told. And so over the first few weeks he learned that most of the people on the project were not devoted to getting the script on the screen, but were devoted to making a picture, any picture, so long as it was cheap. (524)

On the next page, Jerry weakly protests, “But in the book.” “Fuck the book,” Rick Heidelberg, the so-quickly-jaded one-hit wonder of the book, says.

It’s a hard world for writers in Hollywood, Jerry, and probably Carpenter, too, learns. By the time The Lady of the Lake reaches its premiere in the final pages of the novel, Jerry is so far down on the credits that he’s almost not there, hidden away with Raymond Chandler, author of the “source material.” But despite this bleak ending, there is another ending which spells hope for our hero. It’s probably the kind of ambivalent way that Carpenter himself felt about Hollywood. For, despite only minimal success there, he worked and lived in the business – and chronicled it in his fiction – for more than a decade.

John Duncan Talbird is the author of the just-released, limited edition book of stories, A Modicum of Mankind (Norte Maar) with images by artist Leslie Kerby. His fiction and essays have recently appeared or are forthcoming in Ploughshares, Juked, The Literary Review, Amoskeag, REAL and elsewhere. An English professor at Queensborough Community College, he lives with his wife in Brooklyn.