By Elias Savada.

Here’s a thought. Flip through the opening lines of an imagined screenplay for The Wolfpack…. It’s dusk. The Empire State Building centers the landscape, but a chain link boundary obscures the view. It’s a prison metaphor, and the film’s principals, the brothers of this stranger-than-fiction tale, liken their situation to keeping society’s wolves at bay or preventing a mother’s lambs from wandering afield. So, who’s on which side of the fence?

A broken window in the Lower East Side housing project where the Angulo family lives (soft-spoken Midwest mom Susanne; domineering Peruvian, Hare Krishna-inspired dad Oscar; seven long-haired kids with strange Sanskrit names) provides a glimpse to the outside world with its view of traffic-clogged city streets. Down there is the enemy. Maybe not a murderous, nasty comic book-based mastermind, but rather a throbbing, networked, socially active community that is out to disrupt their lifestyle. Under the father’s strict control this never-talk-to-strangers family, shut off from the pleasures of play dates and friends for most of the children’s formative years, isn’t agoraphobic. Yet to them, as home-schooled by mom and instructed by dad, everyone else is part of a bad environment where a walk in the neighborhood would be greeted by death or drugs. The best solution, as seen in Crystalle Moselle’s unsettling debut documentary feature, is to steer clear of the world around them. For some reason (I don’t think the film answers why), the parents leave them one means of escape.

Movies.

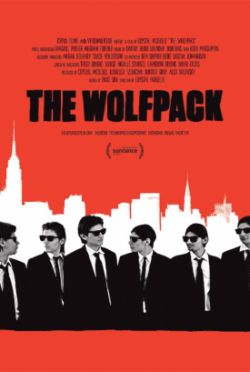

Cut off from personal contact with the civilized planet for more than a decade and not allowed to plug in to the world wide web, they instead devour thousands of Hollywood movies, watching VHS tapes and DVDs together on an aging cathode ray tube television balanced on cinder blocks. In fact, the kids live from one scene they reproduce, to the next. They make hand-drawn poster art, fake guns, and amateurish costumes out of everyday items (yoga mats, cereal boxes, paint), fueling their occasionally-videotaped recreations from classic melodramas ranging from Pulp Fiction to Goodfellas to any of the Christopher Nolan Batman films. Sometimes, the boys appear in their Reservoir Dogs wardrobe — dark suits, collared shirts, black ties, and the requisite shades — when blasting one another with fake weaponry. The low-budget quality of these wildly violent movie homages are similar to those employed in the Sundance charmer Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, but used to a much different end. God bless home movies.

Cut off from personal contact with the civilized planet for more than a decade and not allowed to plug in to the world wide web, they instead devour thousands of Hollywood movies, watching VHS tapes and DVDs together on an aging cathode ray tube television balanced on cinder blocks. In fact, the kids live from one scene they reproduce, to the next. They make hand-drawn poster art, fake guns, and amateurish costumes out of everyday items (yoga mats, cereal boxes, paint), fueling their occasionally-videotaped recreations from classic melodramas ranging from Pulp Fiction to Goodfellas to any of the Christopher Nolan Batman films. Sometimes, the boys appear in their Reservoir Dogs wardrobe — dark suits, collared shirts, black ties, and the requisite shades — when blasting one another with fake weaponry. The low-budget quality of these wildly violent movie homages are similar to those employed in the Sundance charmer Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, but used to a much different end. God bless home movies.

The second half of the film follows the boys as they move away from their cocoon and out into the world, including a group excursion to the beach at Coney Island. All but one hit the water. Their slender, pale bodies could use some color.

The numerous interviews and snippets from the older home videos are interwoven nicely by Moselle and her editor Enat Sidi (Jesus Camp, Detropia, Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me) and blended with the dissonant music score by Danny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans, with Aska Matsumiya.

With a middle-class, suburban upbringing, it’s hard for me to understand the psychology behind families like the Angulos. Most of the people in such situations end up in court, jail, and even on the evening news. Could the cosmic connection that brought the filmmaker into this family have created the perfect storm conditions for their eventual escape from the incredible disconnect they had been living up to that point? I can’t adequately answer that, but it is the boys’ love for cinema, especially Narayana (“If I didn’t have movies, life would be pretty boring”), that allowed director Moselle to stumble into their lives 5 years ago. And stay. Had Moselle been an accountant, a doctor, a social worker, the story would have had a different, unseen ending. And probably a sad one. You wouldn’t be watching this movie.

The film premiered at Sundance at the beginning of the year, winning a documentary grand jury prize, and ends its festival run this week at AFI DOCS, a week after opening its theatrical engagement in New York City.

Elias Savada is a movie copyright researcher, critic, craft beer geek, and avid genealogist based in Bethesda, Maryland. He helps program the Spooky Movie International Movie Film Festival, and previously reviewed for Film Threat and Nitrate Online. He is an executive producer of the new horror film German Angst and co-author, with David J. Skal, of Dark Carnival: the Secret World of Tod Browning.