A book review by Tony Williams.

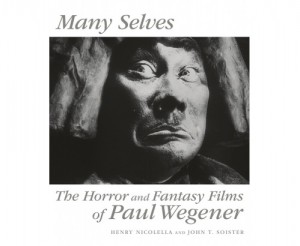

Though mostly well known to western audiences for playing the title characters in The Student of Prague (1913), The Golem (1920), and Rex Ingram‘s The Magician (1926) as well as appearances in Nazi-era films such as Der Grosse Koenig (1941) and Kolberg (1945), Paul Wegener’s cultural significance is virtually unknown outside Germany. While German language studies exist to film in the gaps such as Heide Schoenemann’s magnificent Paul Wegener: Fruehe Moderne im Film (2003), well worth the effort for anyone with a reading knowledge of the language and sorely needing translation, an English book on the actor-director has been conspicuous by its absence so far. Fortunately, this gap has been partially filled by this book written by two experts on silent cinema, Henry Nicolella and John T. Soister, who have chosen to concentrate on Wegener’s involvement in the specific genres of fantasy and horror whether as actor and/or director as opposed to Schoenemann who examines Wegener’s work as director in the context of his other interests in folk tales and Eastern culture. While one might lament the appearance of a more comprehensive book covering Wegener’s other films and theatrical roles, the co-authors have wisely decided to limit themselves to defining Wegener’s importance in the horror and fantasy genres while also supplying a chronological filmography of his other work for those interested in following other trails.

A key virtue of this book is that the authors have (with one exception) managed to see all of Wegener’s surviving films and fragments whether in German film archives or what may be available on youtube and other internet sources. It begins with a biography with individual chapters covering films such as The Student of Prague, all versions of The Golem whether surviving or not, Ruebezahls Hochzeit (1916, Hans Trutz im Schlaraaffenland (1917,that also features future director Ernst Lubitsch playing a satyr-like Satan), Der Rattenfaenger von Hameln (1918) Nachtgestalten, (1919/20), Der verlorene Schatten (1920), Lebende Buddhas (1923-25), The Magician , Svengali (1927), Ramper der Tiermensch (1927), Alraune (1927) , Fundvogel (1930), and Unheimliche Geschicten (1932). A chronological filmography, bibliography, and index arrive at a total page number of 433. Lebende Buddhas, directed, produced by and starring Wegener was a financial disaster that also saw his separation from then wife and collaborator Lyda Salmanova. This may account for his increasing appearances in films he did not direct at this point in his career. It also featured a minor performance by Asta Nielsen who admired Wegener as “Germany’s greatest interpreter of Strindberg.” (250)

Nicollela has specialized in silent cinema while Soister is known for his books on Conrad Veidt. Both are reputable researchers who left no stone unturned in visiting archives and drawing reader attention to films and/or fragments available today on youtube. They have clearly done their homework in writing a book aimed at the general reader and those academics who wish to explore further. But one regrets the often jocular remarks they often insert into the text that often provoke irritation rather than amusement. However, this is a minor flaw in terms of the excavation work they have undertaken in providing English language readers with descriptions of Wegener’s films although in many cases more emphasis on visual detail may be more preferable to dependence on plot synopsis. Herzog Ferrantes Ende (1922), directed, scripted by and starring Wegener does not fit into the fantasy or horror emphasis of this book so appears via synopsis in the chronological filmography. However, several stills and a good detailed description of this missing film described as a masterpiece by Henri Langlois (362) can be found in Schoenemann. However, for this and other films listed in the section, references to visual nuances contained in Wegener’s performances are often missing. The first version of The Golem (1914/15) is not as bad as the description given in the main section of the book so youtube footage of surviving fragments should be consulted here.

Nicollela has specialized in silent cinema while Soister is known for his books on Conrad Veidt. Both are reputable researchers who left no stone unturned in visiting archives and drawing reader attention to films and/or fragments available today on youtube. They have clearly done their homework in writing a book aimed at the general reader and those academics who wish to explore further. But one regrets the often jocular remarks they often insert into the text that often provoke irritation rather than amusement. However, this is a minor flaw in terms of the excavation work they have undertaken in providing English language readers with descriptions of Wegener’s films although in many cases more emphasis on visual detail may be more preferable to dependence on plot synopsis. Herzog Ferrantes Ende (1922), directed, scripted by and starring Wegener does not fit into the fantasy or horror emphasis of this book so appears via synopsis in the chronological filmography. However, several stills and a good detailed description of this missing film described as a masterpiece by Henri Langlois (362) can be found in Schoenemann. However, for this and other films listed in the section, references to visual nuances contained in Wegener’s performances are often missing. The first version of The Golem (1914/15) is not as bad as the description given in the main section of the book so youtube footage of surviving fragments should be consulted here.

However, these are just personal issues. Overall, this book is a very valuable contribution to film history that should stimulate further research and more English language work on this neglected actor. Research and information concerning Wegener’s collaborators such as Richard Oswald, a figure worthy of an English language book himself, is also a key aspect of this book. The authors point out that he saved many German females from rape by the victorious Red Army while Schoenemann also mentions that the invading Russian forces knew and respected his work even hanging a banner outside is house, “This is the home of the great Paul Wegener.” Wegener also protected many Jews during this period so his involvement in Nazi films during this era may be more complex than it appears to be. Again, this is a subject needing further research. Although Wegener directed Eine Mann will nach Deutschland (1934) about patriotic Germans attempting to get home during World War One and appeared as the commissar in Hans Westmar (1932) and the malevolent British officer in Mein Leben fur Irland (1940/41) his performances in these films are more evocative of subdued high camp villains than the pro-Nazi attitudes espoused by Heinrich George in the many films he appeared in at this time. As Schoenemann suggests, Wegener’s Asiatic looking features, his interests in fantasy and Orientalism may have placed him under suspicion at this time although he never left Germany as did Dietrich, Veidt, and others. At the same time, one would have hated seeing him perform the type of roles available to those distinguished émigrés such as Fitz Kortner and others in Hollywood assuming he would have transcended the language barrier. Significantly, his last posthumously released film The Great Mandarin (1948/49) saw him appearing as himself in a film about peace and social justice. Unlike Emil Jannings, the Occupation did see his return to film.

Finally, a word of praise should go to Bear Manor Press for producing this book. As an independent maverick publishing house that has published autobiographies of Johnny Holmes and Seka as well as veteran actor James Best along with much-need informative ones on Jack Kelly, Ann Harding, and Dan Duryea, they have brought out something really significant and contributed to the worrying gap of information in film studies today with the economic caution and price of academic and mainstream publishers. I not only hope that they will publish other key works but also that aspiring authors will go to their site and discover the unique generous reimbursements they give to writers unparalleled elsewhere. With publishing venues becoming scarce for books regarded elsewhere as non-marketable, it is important the independent sector receives encouragement especially with direct-to-library publishers such as McFarland and Rowman and Littlefield now using peer group evaluation formerly confined to the academic sector. I do not know if Bear Manor Press uses this method but Many Selves: The Horror Film and Fantasy Films of Paul Wegener deserves a wider market. Among its merits are references from contemporary sources concerning Wegener’s films and follow-up suggestions for those not only wishing to further the pioneer trail of this particular English work but also to produce other future studies.

Tony Williams is Professor and Area Head of Film Studies in the Department of English, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. He is currently reading the novels of Sir Walter Scott and enjoying the films of Wheeler and Woolsey.