A Book Review by John Duncan Talbird.

Many film lovers will enjoy Patton Oswalt’s new memoir, Silver Screen Fiend, mainly because he’s one of us. He and his friends – “sprocket fiends” all – when they’re not lurking in revival houses or art house cinemas, spend their times arguing in diners about how George Lucas could have made The Phantom Menace (1999) a little less sucky or problem-solving the flaws of The Godfather: Part III (1990), theorizing Connie Corleone as a “hidden puppet master, like Maerose Prizzi in Prizzi’s Honor” (1985) (161). The love Oswalt has for film – the classics, but also grindhouse, foreign, indie, and mainstream fluff – is more passionate than the average Joe. (In fact, he tells a very funny story about going to see Last Man Standing (1996) with a childhood friend and completely alienating said friend when he informs him that this mediocre Bruce Willis vehicle they’re about to watch is a remake of an Italian film (Fistful of Dollars, 1964) which was a remake of a Japanese film (Yojimbo, 1961) which were all an adaptation of the source material, Dashiel Hammet’s 1929 novel, Red Harvest.) However, just because he’s more passionate, I’m not sure that his passion leads up to the addiction referenced in the subtitle of the memoir: “Learning About Life from an Addiction to Film.” We have the movies he watched over a four-year period in the back of the book and it averages to about three a week – more than average, but not addiction-worthy. Anyone who’s seen IFC’s mercifully brief Ultimate Film Fanatic (2004-2005) game show will know this; I remember seeing a contestant who, one year, watched at least a movie every day of the year (like Oswalt, all in the theater – movies at home didn’t count).

Ultimately, though, despite the subtitle, this memoir isn’t about addiction to film or even really film that much. It’s about art and passion and, most importantly, about the borderline between making art and consuming it. Many readers will be aware of Oswalt as a very funny comedian. Of course, Oswalt was a long-running cast member on the sitcom The King of Queens (1998-2007), the lead voice in Ratatouille (2007), and the moral center of Jason Reitman’s nihilistically dark comedy Young Adult (2011). However, most important – at least for this memoir – is his first love: stand-up comedy. In these years, the mid-to-late ‘90s, Oswalt was cutting his teeth in the alternative comedy scene of downtown L.A., going from film screenings to stand-up and back again to midnight movies. His ultimate goal: to be a movie director. Like a lot of young wannabe movie-makers in the 1990s, in L.A. and elsewhere, he was influenced by the story of Quentin Tarantino, a nobody movie buff video store clerk who became one of the most famous (or infamous depending on your point of view) American directors in the history of cinema. This is the most interesting aspect of Oswalt’s memoir and what I wish he had spent more time examining: How being a fan/viewer is different than being a creator/producer. In fact, I’m not sure he realizes that this is the story he’s telling. He seems to think that his “addiction” was keeping him from doing the real work to make himself the filmmaker he had always dreamed himself capable of being.

There is a central theory of art that undergirds this memoir, something that Oswalt calls “The Night Café” after Van Gogh’s painting of the same name. Early in the book, Oswalt argues that artists all experience something like this. Van Gogh was painting pretty conventional landscapes and still lives and then he painted this painting which broke through tradition and allowed him to paint all his world-changing paintings afterward (and, Oswalt hints, perhaps, led to his eventual insanity and death – yawn!). Oswalt says that he experienced several of these: watching Nosferatu (1922) as a child, doing stand-up at an open-mic as a college student, bombing at stand-up in front of other more impressive comedians in San Francisco years later, etc. The truth is that a lot of this seems like the middlebrow theorizing of someone who wants to write Something Important. As I read this, I find myself flipping to the back of the dust jacket, rereading all the funny people – Ricky Gervais, Amy Schumer, Joss Whedon – shrieking at me in all-caps about how funny this book is. Where is the funny? I wonder. Sure, it’s pushing into quirky territory with ironic footnotes on many pages, some footnotes that comment on their own footnoted-ness, but this is not new territory for anyone who has read more than two postmodern fiction writers. And then, at some point, I realized that I was enjoying this book and sometimes even laughing. Because this book is about passion and it’s about not losing your passion even amidst failure and self-loathing and embarrassment. And it’s not cheesy like a self-help book, but it’s sharp and funny and sometimes wicked.

There is a central theory of art that undergirds this memoir, something that Oswalt calls “The Night Café” after Van Gogh’s painting of the same name. Early in the book, Oswalt argues that artists all experience something like this. Van Gogh was painting pretty conventional landscapes and still lives and then he painted this painting which broke through tradition and allowed him to paint all his world-changing paintings afterward (and, Oswalt hints, perhaps, led to his eventual insanity and death – yawn!). Oswalt says that he experienced several of these: watching Nosferatu (1922) as a child, doing stand-up at an open-mic as a college student, bombing at stand-up in front of other more impressive comedians in San Francisco years later, etc. The truth is that a lot of this seems like the middlebrow theorizing of someone who wants to write Something Important. As I read this, I find myself flipping to the back of the dust jacket, rereading all the funny people – Ricky Gervais, Amy Schumer, Joss Whedon – shrieking at me in all-caps about how funny this book is. Where is the funny? I wonder. Sure, it’s pushing into quirky territory with ironic footnotes on many pages, some footnotes that comment on their own footnoted-ness, but this is not new territory for anyone who has read more than two postmodern fiction writers. And then, at some point, I realized that I was enjoying this book and sometimes even laughing. Because this book is about passion and it’s about not losing your passion even amidst failure and self-loathing and embarrassment. And it’s not cheesy like a self-help book, but it’s sharp and funny and sometimes wicked.

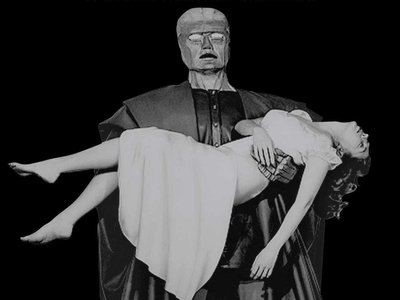

Oswalt tells a hilarious story about how he and his friends (David Cross, Bob Odenkirk, and other famous comedians before they were famous) put on a regular L.A. performance of Jerry Lewis’ unreleased clown-in-Auschwitz dramatic comedy, The Day the Clown Died (1972) until they were threatened with litigation. He tells another funny story about a friend who comes out to L.A. to do stand-up even though he hasn’t performed in eight years because he’s seen Oswalt on TV and also wants to “get a TV show.” Some of these stories, like Oswalt’s comedy act, are dark and they make you squirm. But like his act he’s never mean; there’s a warmness to the telling. We come to learn that Oswalt understands what he’s doing on the stage and in front of the camera and has managed to be so successful at it – despite the fact that he still hasn’t directed a film – because he understands both the vulnerability and risk involved in making art and also the desire for something really good by those of us who keep going to the comedy clubs and movie theaters, sitting in the dark and waiting for it all to begin.

John Duncan Talbird is the author of the limited edition book of stories, A Modicum of Mankind (Norte Maar) with images by artist Leslie Kerby. His fiction and essays have recently appeared or are forthcoming in Ploughshares, Juked, The Literary Review, Amoskeag, REAL, and elsewhere. An English professor at Queensborough Community College, he lives with his wife in Queens, NY, USA.