Av: Christina Parte

The fact that Eija-Riitta Eklöf (1954-2015) passed

away a few years ago would have gone unnoticed had she not been in love with

the Berlin Wall. In Lars Laumann’s filmic portrait Berlinmuren (2008), we hear the

late Eija-Riitta speak as we are introduced to her world through a collection

of objects in her immediate surrounding. This combination of live footage,

personal mementos as well as archival material stages her special relation to

objects in a subtle way. Eija-Riitta was a self-declared objectum sexual, who

was sexually and emotionally attracted to objects with a rectangular form,

parallel lines and a dividing function. She saw herself as an animist not a

fetishist and believed that all objects were living beings, which were not only

invested with a soul but also communicated directly with her. Her home in

Sweden was animated by a large number of cats and an equally large amount of

scale models including fences, bridges, guillotines and the Berlin Wall.

Eija-Riitta allegedly married the Berlin Wall in 1979 and changed her last name

from Eklöf to Berliner-Mauer. Ever since she had first seen the Berlin Wall on

TV in 1961, she had felt an intense attraction to him. In Berlinmuren,

we learn that Eija-Riitta visited her husband several times in situ but

mostly contented herself with self-made scale models of the Berlin Wall, which

she treated as living extensions of the original.

Berlinmuren, 2008

video for projection

23 minutes 56 seconds

© Lars Laumann, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

In one of the photographs taken at the Berlin Wall and shown in Berlinmuren,

a woman with dark sunglasses kneels against an individual segment, a smirk on

her face. What looks like a fairly conventional snap shot, shows Eija-Riitta

leaning against and touching the Wall, while in the right-hand corner of the

photograph the scale model of an earlier generation of the Wall strikes a

similar pose. The small but essential detail could easily be overlooked if

Eija-Riitta’s loving hand on the Wall’s base together with the white shopping

bag scattered in front of it did not point towards the model, forming an

unlikely love triangle.

The fact that the Berlin Wall fell and was eventually demolished, was

experienced as a catastrophe by Eija-Riitta, who championed object rights and

denounced the demolition of the Berlin Wall after its fall. In Berlinmuren

she admitted to having repressed the traumatic event and preferred to see her

husband as past his prime. Lars Laumann’s montage of postcards, photos and film

clips foregrounds her loving rather than sexual relatedness to objects.

Nevertheless, a fetishistic structure of desire vis a vis her object choice

comes to the fore. Despite her personal disinterest in politics, Eija-Riitta

was well aware that the Berlin Wall embodied the division between capitalism

and communism in a city cut into two halves. The overabundance of Berlin Wall

models -some of them playfully obstructed doors- accurately revealed their

domineering function in her personal space.

The all too often painfully divisive impact of the original objects she

felt sexually attracted to -think of the guillotines!- was displaced by the use

of scale models but not entirely erased as the accumulation of obstacles in her

house confirms.

Neither on her website nor in Laumann’s video is the Wall as an actual

fortification system with its frontline and hinterland walls, its watch towers

and death strip ever shown. Eija-Riitta exclusively loved the Western Wall, in

front of which she posed for photographs to be taken, with or without a model

wall in one of her hands. In this way, not only the Berlin Wall’s symbolic

character and historical dividing function but also its material structure was

negated, only to re-emerge in slightly distorted form.

While capturing the arrangement of objects in Eija-Riitta’s house,

Laumann’s camera focuses at one point on the attentive eyes of a black cat,

comfortably resting in the space between Western Wall model and window. Staring

at the viewer from the other side and scanning the terrain in front, the cat’s

gaze ironically alludes to a border guard’s weighty responsibilities. The cat

is backlit which heightens the effect of being watched and the whole scene

reminds of the brightly lit death strip behind the frontline wall in nocturnal,

divided Berlin. Eija-Riitta tolerated her cats, whose photographs appeared

lovingly side by side with pictures of the Berlin Wall in her house, but she

feared them just as well. She felt that her feline companions posed an

existential threat to the models’ existence. Unlike the military guardians of

the Wall, the cats could always knock over the models and, on the symbolic as

well as structural level, overcome their divisive function. In Eija-Riitta’s

topsy turvy world cats played games with walls and walls could perish.

Rather than dismissing Eija-Riitta’s relation to objects as fetishism tout

court, this is fetishism with a twist. While Freud taught us that the fetish’s

function was to cover up an unwelcome sight – the mother lacking the penis –

Eija-Riitta fetishized the dividing agent that created lack in the first place.

Instead of phallic plenty, painful forms of division calmed Eija-Riitta’s

nerves and delighted her senses. Eija-Riitta did not crave re-unification but

welcomed the Wall and was captivated by its form.

The fetish as symptomatic signifier, according to Laura Mulvey, points to a

psychological and social structure that disavows knowledge in favor of belief.

The fetish is characterized by a double structure. Its spectacular form

distracts from something, which needs to be concealed. However, the greater the

distraction, the more obvious the need for concealment.

The more harmless and beautifully crafted Eija-Riitta’s scale models

appeared, the more disturbing their function in reality, from geopolitical

division to beheading, became. Even though Eija-Riitta lived with her objects

in a subject to subject relationship, treating them as beings, some of them allegedly

wanted to be put on display and thus became objects to be looked at in her

small museum or to be hung as pictures on the walls of her house.

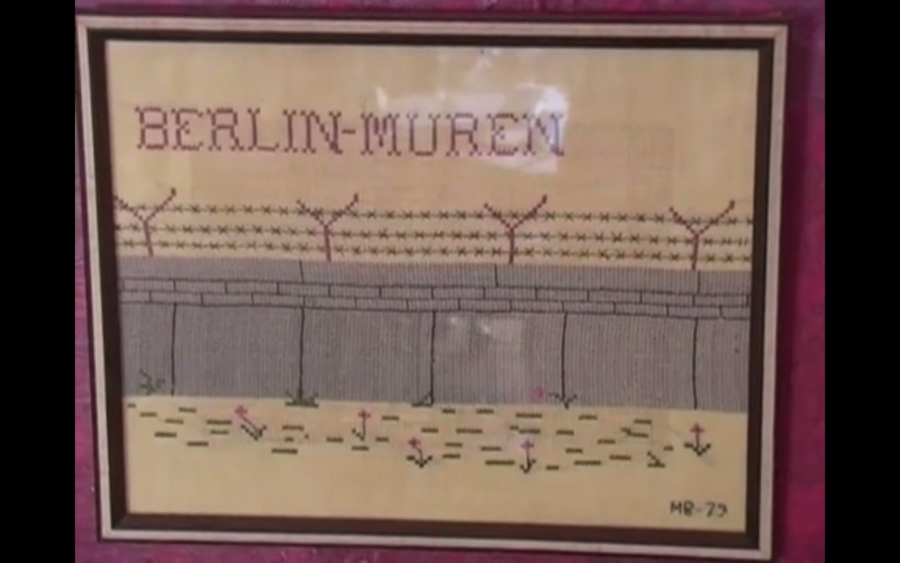

Eija-Riitta seemed particularly attracted to the forbidding character of

the first generation of the Berlin Wall, whose concrete block structure was

finished off by a y-shaped line of barbed wire. While martial and threatening

in reality, Eija-Riitta’s Wall turned into a piece of domestic bliss. As neat

embroidery, the first generation of the Wall became perfectly fitting wall

decoration.

Berlinmuren, 2008

video for projection

23 minutes 56 seconds

© Lars Laumann, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

By keeping the form but changing the size, material and context of her

object of desire, Eija-Riitta appropriated and subverted a symbolically charged

and highly contested border wall. Her strategy epitomized a dangerously cute

aesthetics, which, in contemporary Japanese culture, as Sianne Ngai points out,

is characterized by ambivalence, the oscillation between kawaii and kowai (cute

and scary). Takashi Murakami’s Pop Art-inspired trademark Mr. DOB figures, which range from cute incarnations of a

cartoon-mouse-like figure to rather disturbing images of beings dominated by

their eyes and bare teeth, serve as a good example. Ngai defines cute

aesthetics as aesthetics of powerlessness, where the exaggerated cuteness of

objects can also provoke sadistic impulses of the subject, who derives

pleasure, not from cuddling the cute object, but from testing the object’s

resistance to rough handling. In a dialectical reversal, the subject’s veiled

or latent aggression can turn into explicit violence. Whether behind

Eija-Riitta’s militant activism for object rights was also a desire to master

and control them is up to speculation. She certainly turned the issue of the

Berlin Wall’s demolition into a political tool when vehemently criticizing so

called wall peckers, people, who chiseled off pieces of the Western Wall as

personal mementos or for profit after its fall in 1989.

Even more upsetting for Eija-Riitta was the fact that individual graffitied

pieces were eventually auctioned off, sold or sent to museums and private

collections around the world. The Berlin Wall was not only mutilated but

exploited and turned into a commodity for sale. Only one framed newspaper

article recalled the traumatic event of the fall of the Wall on the 9th of November 1989 in

Eija-Riitta’s house. In her eyes, the Berlin Wall was a German being, who

belonged to West and East Germany, which should not have been reunited. The

only way out of the dilemma seemed to be screening off an event, which for most

of her German contemporaries was greeted with wonder, joy and disbelief.

Eija-Riitta’s imaginary identification with and empathy for the Berlin Wall as

vulnerable, deformed being, was nurtured by the object’s resistance since some

parts of the Wall are still standing. The ability to withstand rough handling,

Sianne Ngai argues, shifts control from subject to object, which persists and

resists. The aggressed mute object returns as an impotence on the part of the

subject and thus, while ruinous and downtrodden, the Wall has not entirely

vanished and remains an obstacle for the living.

Anthropologist Roy Ellen sees the ambiguous relationship between the

control of objects by people and of people by objects as one of the defining

characteristics of fetishism. Ellen emphasizes the universal human character of

fetish-like behavior, which can be found in everyday practices of

anthropomorphism and the tendency to conflate, in semiotic terms, the signifier

and the signified, the tempting belief that the representation equals the

represented object. It is therefore not surprising that graffitied fragments of

the Western Wall were kept by many Berliners and tourists as souvenirs,

trophies, even relics or turned into commodities for sale. Almost overnight a

forbidding military fortification system had become accessible and many desired

a piece of the Wall. In the end, the Wall rather than being terrifying, turned

out to be terrific.

The successful appropriation of Berlin Wall fragments after its fall reminds

of the storming of the Bastille in 1789, which had also turned from symbol of

state oppression into symbol of freedom. Already in 1789, the potential for the

commodification of the fragments of a formerly threatening object such as the

Bastille prison was identified by French revolutionist Pierre-Francois Palloy.

He started trading in miniatures of the Bastille carved from the dismantled

blocks of the former prison.

The conspicuous consumption of the Berlin Wall however, has a longer

history, which is due to the Wall’s paradoxical status. The Wall as

fortification system and object of division between East and West Berlin and

its ever changing, aestheticised Western façade not only deterred and enraged

but also impressed, fascinated and confused the Western onlooker. The

continuous technical improvement of the different generations of the Wall went

hand in hand with their aestheticisation. Quite intentionally, art historian

Michael Diers argues, GDR strategists hoped that an aesthetically pleasing, at

later stages whitewashed, Western façade would eventually turn the Wall into an

invisible monument. While monumental invisibility was countered by a Western

onslaught of colorful graffiti and faux-naïve wall art in the 1980s, the

emerging aesthetics of the Western Wall’s façade prompted the growing

commodification of the Wall.

More and more tourists wanted their pictures taken in front of West

Berlin’s number one attraction and graffiti writers and Wall artists sought a

short cut to fame by leaving their marks on the Berlin Wall. The

spectacularized stretch of the Western Wall between Potsdamer Platz and

Checkpoint Charlie functioned as a screen screening off the GDR fortification

system and the imprisonment of GDR citizens. Instead, it reflected back its lively,

graffitied side to the West. The sheer abundance of inoffensive, if not cute,

images overriding the sparse presence of political graffiti, the excessive

shine between Checkpoint Charlie and Brandenburger Tor in the 1980s, barely

veiled the fetish’s structural violence: a simple, all too often fascinated

than sympathetic, look across the Western Wall from a Western observation

platform destroyed the illusion. The Berlin Wall was built in reverse order.

The fortification system faced East not West. The actual frontline wall was the

hinterland wall followed by signal fences, watchtowers, dog runs, control

strips, anti-vehicle barriers and finally the fairly insignificant, frontline

wall, generally known as the Berlin Wall.

Brought wonderfully to the foreground through Eija-Riitta’s provocative

desire for the Wall’s existence is the underside of the Berlin imaginary.

Despite its symbolic relevance and visual saturation, the Western Wall played

only a minor role for military strategists and could easily be appropriated for

other purposes. Not only Eija-Riitta mourned and rejected the loss of a highly

contested object.